Chapter 3 - Advanced Request-Reply Patterns #

In Chapter 2 - Sockets and Patterns we worked through the basics of using ZeroMQ by developing a series of small applications, each time exploring new aspects of ZeroMQ. We’ll continue this approach in this chapter as we explore advanced patterns built on top of ZeroMQ’s core request-reply pattern.

We’ll cover:

- How the request-reply mechanisms work

- How to combine REQ, REP, DEALER, and ROUTER sockets

- How ROUTER sockets work, in detail

- The load balancing pattern

- Building a simple load balancing message broker

- Designing a high-level API for ZeroMQ

- Building an asynchronous request-reply server

- A detailed inter-broker routing example

The Request-Reply Mechanisms #

We already looked briefly at multipart messages. Let’s now look at a major use case, which is reply message envelopes. An envelope is a way of safely packaging up data with an address, without touching the data itself. By separating reply addresses into an envelope we make it possible to write general purpose intermediaries such as APIs and proxies that create, read, and remove addresses no matter what the message payload or structure is.

In the request-reply pattern, the envelope holds the return address for replies. It is how a ZeroMQ network with no state can create round-trip request-reply dialogs.

When you use REQ and REP sockets you don’t even see envelopes; these sockets deal with them automatically. But for most of the interesting request-reply patterns, you’ll want to understand envelopes and particularly ROUTER sockets. We’ll work through this step-by-step.

The Simple Reply Envelope #

A request-reply exchange consists of a request message, and an eventual reply message. In the simple request-reply pattern, there’s one reply for each request. In more advanced patterns, requests and replies can flow asynchronously. However, the reply envelope always works the same way.

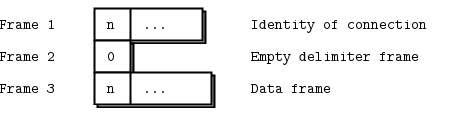

The ZeroMQ reply envelope formally consists of zero or more reply addresses, followed by an empty frame (the envelope delimiter), followed by the message body (zero or more frames). The envelope is created by multiple sockets working together in a chain. We’ll break this down.

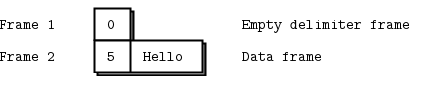

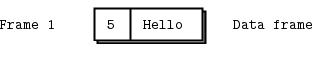

We’ll start by sending “Hello” through a REQ socket. The REQ socket creates the simplest possible reply envelope, which has no addresses, just an empty delimiter frame and the message frame containing the “Hello” string. This is a two-frame message.

The REP socket does the matching work: it strips off the envelope, up to and including the delimiter frame, saves the whole envelope, and passes the “Hello” string up the application. Thus our original Hello World example used request-reply envelopes internally, but the application never saw them.

If you spy on the network data flowing between hwclient and hwserver, this is what you’ll see: every request and every reply is in fact two frames, an empty frame and then the body. It doesn’t seem to make much sense for a simple REQ-REP dialog. However you’ll see the reason when we explore how ROUTER and DEALER handle envelopes.

The Extended Reply Envelope #

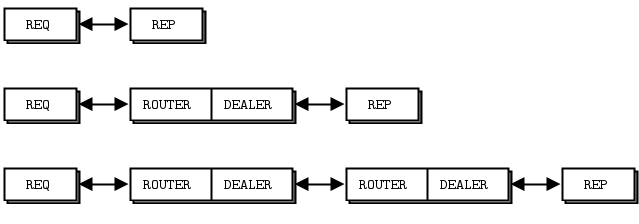

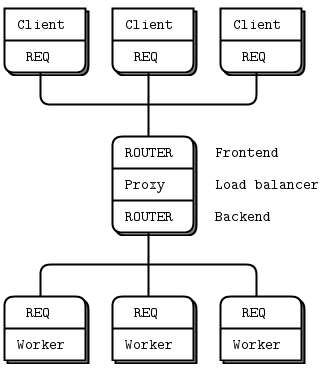

Now let’s extend the REQ-REP pair with a ROUTER-DEALER proxy in the middle and see how this affects the reply envelope. This is the extended request-reply pattern we already saw in Chapter 2 - Sockets and Patterns. We can, in fact, insert any number of proxy steps. The mechanics are the same.

The proxy does this, in pseudo-code:

prepare context, frontend and backend sockets

while true:

poll on both sockets

if frontend had input:

read all frames from frontend

send to backend

if backend had input:

read all frames from backend

send to frontend

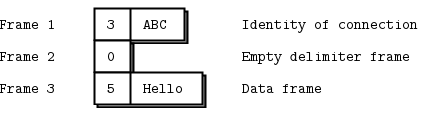

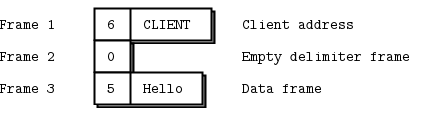

The ROUTER socket, unlike other sockets, tracks every connection it has, and tells the caller about these. The way it tells the caller is to stick the connection identity in front of each message received. An identity, sometimes called an address, is just a binary string with no meaning except “this is a unique handle to the connection”. Then, when you send a message via a ROUTER socket, you first send an identity frame.

The zmq_socket() man page describes it thus:

When receiving messages a ZMQ_ROUTER socket shall prepend a message part containing the identity of the originating peer to the message before passing it to the application. Messages received are fair-queued from among all connected peers. When sending messages a ZMQ_ROUTER socket shall remove the first part of the message and use it to determine the identity of the peer the message shall be routed to.

As a historical note, ZeroMQ v2.2 and earlier use UUIDs as identities. ZeroMQ v3.0 and later generate a 5 byte identity by default (0 + a random 32bit integer). There’s some impact on network performance, but only when you use multiple proxy hops, which is rare. Mostly the change was to simplify building libzmq by removing the dependency on a UUID library.

Identities are a difficult concept to understand, but it’s essential if you want to become a ZeroMQ expert. The ROUTER socket invents a random identity for each connection with which it works. If there are three REQ sockets connected to a ROUTER socket, it will invent three random identities, one for each REQ socket.

So if we continue our worked example, let’s say the REQ socket has a 3-byte identity ABC. Internally, this means the ROUTER socket keeps a hash table where it can search for ABC and find the TCP connection for the REQ socket.

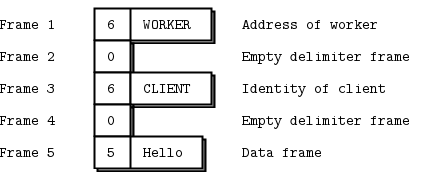

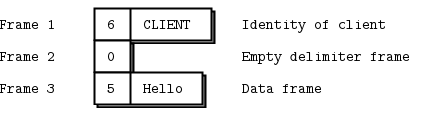

When we receive the message off the ROUTER socket, we get three frames.

The core of the proxy loop is “read from one socket, write to the other”, so we literally send these three frames out on the DEALER socket. If you now sniffed the network traffic, you would see these three frames flying from the DEALER socket to the REP socket. The REP socket does as before, strips off the whole envelope including the new reply address, and once again delivers the “Hello” to the caller.

Incidentally the REP socket can only deal with one request-reply exchange at a time, which is why if you try to read multiple requests or send multiple replies without sticking to a strict recv-send cycle, it gives an error.

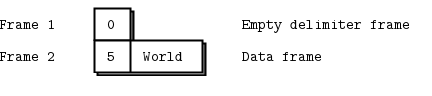

You should now be able to visualize the return path. When hwserver sends “World” back, the REP socket wraps that with the envelope it saved, and sends a three-frame reply message across the wire to the DEALER socket.

Now the DEALER reads these three frames, and sends all three out via the ROUTER socket. The ROUTER takes the first frame for the message, which is the ABC identity, and looks up the connection for this. If it finds that, it then pumps the next two frames out onto the wire.

The REQ socket picks this message up, and checks that the first frame is the empty delimiter, which it is. The REQ socket discards that frame and passes “World” to the calling application, which prints it out to the amazement of the younger us looking at ZeroMQ for the first time.

What’s This Good For? #

To be honest, the use cases for strict request-reply or extended request-reply are somewhat limited. For one thing, there’s no easy way to recover from common failures like the server crashing due to buggy application code. We’ll see more about this in Chapter 4 - Reliable Request-Reply Patterns. However once you grasp the way these four sockets deal with envelopes, and how they talk to each other, you can do very useful things. We saw how ROUTER uses the reply envelope to decide which client REQ socket to route a reply back to. Now let’s express this another way:

- Each time ROUTER gives you a message, it tells you what peer that came from, as an identity.

- You can use this with a hash table (with the identity as key) to track new peers as they arrive.

- ROUTER will route messages asynchronously to any peer connected to it, if you prefix the identity as the first frame of the message.

ROUTER sockets don’t care about the whole envelope. They don’t know anything about the empty delimiter. All they care about is that one identity frame that lets them figure out which connection to send a message to.

Recap of Request-Reply Sockets #

Let’s recap this:

-

The REQ socket sends, to the network, an empty delimiter frame in front of the message data. REQ sockets are synchronous. REQ sockets always send one request and then wait for one reply. REQ sockets talk to one peer at a time. If you connect a REQ socket to multiple peers, requests are distributed to and replies expected from each peer one turn at a time.

-

The REP socket reads and saves all identity frames up to and including the empty delimiter, then passes the following frame or frames to the caller. REP sockets are synchronous and talk to one peer at a time. If you connect a REP socket to multiple peers, requests are read from peers in fair fashion, and replies are always sent to the same peer that made the last request.

-

The DEALER socket is oblivious to the reply envelope and handles this like any multipart message. DEALER sockets are asynchronous and like PUSH and PULL combined. They distribute sent messages among all connections, and fair-queue received messages from all connections.

-

The ROUTER socket is oblivious to the reply envelope, like DEALER. It creates identities for its connections, and passes these identities to the caller as a first frame in any received message. Conversely, when the caller sends a message, it uses the first message frame as an identity to look up the connection to send to. ROUTERS are asynchronous.

Request-Reply Combinations #

We have four request-reply sockets, each with a certain behavior. We’ve seen how they connect in simple and extended request-reply patterns. But these sockets are building blocks that you can use to solve many problems.

These are the legal combinations:

- REQ to REP

- DEALER to REP

- REQ to ROUTER

- DEALER to ROUTER

- DEALER to DEALER

- ROUTER to ROUTER

And these combinations are invalid (and I’ll explain why):

- REQ to REQ

- REQ to DEALER

- REP to REP

- REP to ROUTER

Here are some tips for remembering the semantics. DEALER is like an asynchronous REQ socket, and ROUTER is like an asynchronous REP socket. Where we use a REQ socket, we can use a DEALER; we just have to read and write the envelope ourselves. Where we use a REP socket, we can stick a ROUTER; we just need to manage the identities ourselves.

Think of REQ and DEALER sockets as “clients” and REP and ROUTER sockets as “servers”. Mostly, you’ll want to bind REP and ROUTER sockets, and connect REQ and DEALER sockets to them. It’s not always going to be this simple, but it is a clean and memorable place to start.

The REQ to REP Combination #

We’ve already covered a REQ client talking to a REP server but let’s take one aspect: the REQ client must initiate the message flow. A REP server cannot talk to a REQ client that hasn’t first sent it a request. Technically, it’s not even possible, and the API also returns an EFSM error if you try it.

The DEALER to REP Combination #

Now, let’s replace the REQ client with a DEALER. This gives us an asynchronous client that can talk to multiple REP servers. If we rewrote the “Hello World” client using DEALER, we’d be able to send off any number of “Hello” requests without waiting for replies.

When we use a DEALER to talk to a REP socket, we must accurately emulate the envelope that the REQ socket would have sent, or the REP socket will discard the message as invalid. So, to send a message, we:

- Send an empty message frame with the MORE flag set; then

- Send the message body.

And when we receive a message, we:

- Receive the first frame and if it’s not empty, discard the whole message;

- Receive the next frame and pass that to the application.

The REQ to ROUTER Combination #

In the same way that we can replace REQ with DEALER, we can replace REP with ROUTER. This gives us an asynchronous server that can talk to multiple REQ clients at the same time. If we rewrote the “Hello World” server using ROUTER, we’d be able to process any number of “Hello” requests in parallel. We saw this in the Chapter 2 - Sockets and Patterns mtserver example.

We can use ROUTER in two distinct ways:

- As a proxy that switches messages between frontend and backend sockets.

- As an application that reads the message and acts on it.

In the first case, the ROUTER simply reads all frames, including the artificial identity frame, and passes them on blindly. In the second case the ROUTER must know the format of the reply envelope it’s being sent. As the other peer is a REQ socket, the ROUTER gets the identity frame, an empty frame, and then the data frame.

The DEALER to ROUTER Combination #

Now we can switch out both REQ and REP with DEALER and ROUTER to get the most powerful socket combination, which is DEALER talking to ROUTER. It gives us asynchronous clients talking to asynchronous servers, where both sides have full control over the message formats.

Because both DEALER and ROUTER can work with arbitrary message formats, if you hope to use these safely, you have to become a little bit of a protocol designer. At the very least you must decide whether you wish to emulate the REQ/REP reply envelope. It depends on whether you actually need to send replies or not.

The DEALER to DEALER Combination #

You can swap a REP with a ROUTER, but you can also swap a REP with a DEALER, if the DEALER is talking to one and only one peer.

When you replace a REP with a DEALER, your worker can suddenly go full asynchronous, sending any number of replies back. The cost is that you have to manage the reply envelopes yourself, and get them right, or nothing at all will work. We’ll see a worked example later. Let’s just say for now that DEALER to DEALER is one of the trickier patterns to get right, and happily it’s rare that we need it.

The ROUTER to ROUTER Combination #

This sounds perfect for N-to-N connections, but it’s the most difficult combination to use. You should avoid it until you are well advanced with ZeroMQ. We’ll see one example it in the Freelance pattern in Chapter 4 - Reliable Request-Reply Patterns, and an alternative DEALER to ROUTER design for peer-to-peer work in Chapter 8 - A Framework for Distributed Computing.

Invalid Combinations #

Mostly, trying to connect clients to clients, or servers to servers is a bad idea and won’t work. However, rather than give general vague warnings, I’ll explain in detail:

-

REQ to REQ: both sides want to start by sending messages to each other, and this could only work if you timed things so that both peers exchanged messages at the same time. It hurts my brain to even think about it.

-

REQ to DEALER: you could in theory do this, but it would break if you added a second REQ because DEALER has no way of sending a reply to the original peer. Thus the REQ socket would get confused, and/or return messages meant for another client.

-

REP to REP: both sides would wait for the other to send the first message.

-

REP to ROUTER: the ROUTER socket can in theory initiate the dialog and send a properly-formatted request, if it knows the REP socket has connected and it knows the identity of that connection. It’s messy and adds nothing over DEALER to ROUTER.

The common thread in this valid versus invalid breakdown is that a ZeroMQ socket connection is always biased towards one peer that binds to an endpoint, and another that connects to that. Further, that which side binds and which side connects is not arbitrary, but follows natural patterns. The side which we expect to “be there” binds: it’ll be a server, a broker, a publisher, a collector. The side that “comes and goes” connects: it’ll be clients and workers. Remembering this will help you design better ZeroMQ architectures.

Exploring ROUTER Sockets #

Let’s look at ROUTER sockets a little closer. We’ve already seen how they work by routing individual messages to specific connections. I’ll explain in more detail how we identify those connections, and what a ROUTER socket does when it can’t send a message.

Identities and Addresses #

The identity concept in ZeroMQ refers specifically to ROUTER sockets and how they identify the connections they have to other sockets. More broadly, identities are used as addresses in the reply envelope. In most cases, the identity is arbitrary and local to the ROUTER socket: it’s a lookup key in a hash table. Independently, a peer can have an address that is physical (a network endpoint like “tcp://192.168.55.117:5670”) or logical (a UUID or email address or other unique key).

An application that uses a ROUTER socket to talk to specific peers can convert a logical address to an identity if it has built the necessary hash table. Because ROUTER sockets only announce the identity of a connection (to a specific peer) when that peer sends a message, you can only really reply to a message, not spontaneously talk to a peer.

This is true even if you flip the rules and make the ROUTER connect to the peer rather than wait for the peer to connect to the ROUTER. However you can force the ROUTER socket to use a logical address in place of its identity. The zmq_setsockopt reference page calls this setting the socket identity. It works as follows:

- The peer application sets the ZMQ_IDENTITY option of its peer socket (DEALER or REQ) before binding or connecting.

- Usually the peer then connects to the already-bound ROUTER socket. But the ROUTER can also connect to the peer.

- At connection time, the peer socket tells the router socket, “please use this identity for this connection”.

- If the peer socket doesn’t say that, the router generates its usual arbitrary random identity for the connection.

- The ROUTER socket now provides this logical address to the application as a prefix identity frame for any messages coming in from that peer.

- The ROUTER also expects the logical address as the prefix identity frame for any outgoing messages.

Here is a simple example of two peers that connect to a ROUTER socket, one that imposes a logical address “PEER2”:

identity: Identity check in Ada

identity: Identity check in Basic

identity: Identity check in C

// Demonstrate request-reply identities

#include "zhelpers.h"

int main (void)

{

void *context = zmq_ctx_new ();

void *sink = zmq_socket (context, ZMQ_ROUTER);

zmq_bind (sink, "inproc://example");

// First allow 0MQ to set the identity

void *anonymous = zmq_socket (context, ZMQ_REQ);

zmq_connect (anonymous, "inproc://example");

s_send (anonymous, "ROUTER uses a generated 5 byte identity");

s_dump (sink);

// Then set the identity ourselves

void *identified = zmq_socket (context, ZMQ_REQ);

zmq_setsockopt (identified, ZMQ_IDENTITY, "PEER2", 5);

zmq_connect (identified, "inproc://example");

s_send (identified, "ROUTER socket uses REQ's socket identity");

s_dump (sink);

zmq_close (sink);

zmq_close (anonymous);

zmq_close (identified);

zmq_ctx_destroy (context);

return 0;

}

identity: Identity check in C++

//

// Demonstrate identities as used by the request-reply pattern. Run this

// program by itself.

//

#include <zmq.hpp>

#include "zhelpers.hpp"

int main () {

zmq::context_t context(1);

zmq::socket_t sink(context, ZMQ_ROUTER);

sink.bind( "inproc://example");

// First allow 0MQ to set the identity

zmq::socket_t anonymous(context, ZMQ_REQ);

anonymous.connect( "inproc://example");

s_send (anonymous, std::string("ROUTER uses a generated 5 byte identity"));

s_dump (sink);

// Then set the identity ourselves

zmq::socket_t identified (context, ZMQ_REQ);

identified.set( zmq::sockopt::routing_id, "PEER2");

identified.connect( "inproc://example");

s_send (identified, std::string("ROUTER socket uses REQ's socket identity"));

s_dump (sink);

return 0;

}

identity: Identity check in C#

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using System.Text;

using System.Threading;

using ZeroMQ;

namespace Examples

{

static partial class Program

{

public static void Identity(string[] args)

{

//

// Demonstrate request-reply identities

//

// Author: metadings

//

using (var context = new ZContext())

using (var sink = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.ROUTER))

{

sink.Bind("inproc://example");

// First allow 0MQ to set the identity

using (var anonymous = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.REQ))

{

anonymous.Connect("inproc://example");

anonymous.Send(new ZFrame("ROUTER uses REQ's generated 5 byte identity"));

}

using (ZMessage msg = sink.ReceiveMessage())

{

msg.DumpZmsg("--------------------------");

}

// Then set the identity ourselves

using (var identified = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.REQ))

{

identified.IdentityString = "PEER2";

identified.Connect("inproc://example");

identified.Send(new ZFrame("ROUTER uses REQ's socket identity"));

}

using (ZMessage msg = sink.ReceiveMessage())

{

msg.DumpZmsg("--------------------------");

}

}

}

}

}

identity: Identity check in CL

;;; -*- Mode:Lisp; Syntax:ANSI-Common-Lisp; -*-

;;;

;;; Demonstrate identities as used by the request-reply pattern in Common Lisp.

;;; Run this program by itself. Note that the utility functions are

;;; provided by zhelpers.lisp. It gets boring for everyone to keep repeating

;;; this code.

;;;

;;; Kamil Shakirov <kamils80@gmail.com>

;;;

(defpackage #:zguide.identity

(:nicknames #:identity)

(:use #:cl #:zhelpers)

(:export #:main))

(in-package :zguide.identity)

(defun main ()

(zmq:with-context (context 1)

(zmq:with-socket (sink context zmq:router)

(zmq:bind sink "inproc://example")

;; First allow 0MQ to set the identity

(zmq:with-socket (anonymous context zmq:req)

(zmq:connect anonymous "inproc://example")

(send-text anonymous "ROUTER uses a generated 5 byte identity")

(dump-socket sink)

;; Then set the identity ourselves

(zmq:with-socket (identified context zmq:req)

(zmq:setsockopt identified zmq:identity "PEER2")

(zmq:connect identified "inproc://example")

(send-text identified "ROUTER socket uses REQ's socket identity")

(dump-socket sink)))))

(cleanup))

identity: Identity check in Delphi

program identity;

//

// Demonstrate identities as used by the request-reply pattern. Run this

// program by itself.

// @author Varga Balazs <bb.varga@gmail.com>

//

{$APPTYPE CONSOLE}

uses

SysUtils

, zmqapi

, zhelpers

;

var

context: TZMQContext;

sink,

anonymous,

identified: TZMQSocket;

begin

context := TZMQContext.create;

sink := context.Socket( stRouter );

sink.bind( 'inproc://example' );

// First allow 0MQ to set the identity

anonymous := context.Socket( stReq );

anonymous.connect( 'inproc://example' );

anonymous.send( 'ROUTER uses a generated 5 byte identity' );

s_dump( sink );

// Then set the identity ourself

identified := context.Socket( stReq );

identified.Identity := 'PEER2';

identified.connect( 'inproc://example' );

identified.send( 'ROUTER socket uses REQ''s socket identity' );

s_dump( sink );

sink.Free;

anonymous.Free;

identified.Free;

context.Free;

end.

identity: Identity check in Erlang

#! /usr/bin/env escript

%%

%% Demonstrate identities as used by the request-reply pattern.

%%

main(_) ->

{ok, Context} = erlzmq:context(),

{ok, Sink} = erlzmq:socket(Context, router),

ok = erlzmq:bind(Sink, "inproc://example"),

%% First allow 0MQ to set the identity

{ok, Anonymous} = erlzmq:socket(Context, req),

ok = erlzmq:connect(Anonymous, "inproc://example"),

ok = erlzmq:send(Anonymous, <<"ROUTER uses a generated 5 byte identity">>),

erlzmq_util:dump(Sink),

%% Then set the identity ourselves

{ok, Identified} = erlzmq:socket(Context, req),

ok = erlzmq:setsockopt(Identified, identity, <<"PEER2">>),

ok = erlzmq:connect(Identified, "inproc://example"),

ok = erlzmq:send(Identified,

<<"ROUTER socket uses REQ's socket identity">>),

erlzmq_util:dump(Sink),

erlzmq:close(Sink),

erlzmq:close(Anonymous),

erlzmq:close(Identified),

erlzmq:term(Context).

identity: Identity check in Elixir

defmodule Identity do

@moduledoc """

Generated by erl2ex (http://github.com/dazuma/erl2ex)

From Erlang source: (Unknown source file)

At: 2019-12-20 13:57:24

"""

def main() do

{:ok, context} = :erlzmq.context()

{:ok, sink} = :erlzmq.socket(context, :router)

:ok = :erlzmq.bind(sink, 'inproc://example')

{:ok, anonymous} = :erlzmq.socket(context, :req)

:ok = :erlzmq.connect(anonymous, 'inproc://example')

:ok = :erlzmq.send(anonymous, "ROUTER uses a generated 5 byte identity")

#:erlzmq_util.dump(sink)

IO.inspect(sink, label: "1. sink")

{:ok, identified} = :erlzmq.socket(context, :req)

:ok = :erlzmq.setsockopt(identified, :identity, "PEER2")

:ok = :erlzmq.connect(identified, 'inproc://example')

:ok = :erlzmq.send(identified, "ROUTER socket uses REQ's socket identity")

#:erlzmq_util.dump(sink)

IO.inspect(sink, label: "2. sink")

:erlzmq.close(sink)

:erlzmq.close(anonymous)

:erlzmq.close(identified)

:erlzmq.term(context)

end

end

Identity.main

identity: Identity check in F#

(*

Demonstrate identities as used by the request-reply pattern. Run this

program by itself. Note that the utility functions s_ are provided by

zhelpers.fs. It gets boring for everyone to keep repeating this code.

*)

#r @"bin/fszmq.dll"

open fszmq

open fszmq.Context

open fszmq.Socket

#load "zhelpers.fs"

let main () =

use context = new Context(1)

use sink = route context

"inproc://example" |> bind sink

// first allow 0MQ to set the identity

use anonymous = req context

"inproc://example" |> connect anonymous

"ROUTER uses a generated 5 byte identity" |> s_send anonymous

s_dump sink

// then set the identity ourselves

use identified = req context

(ZMQ.IDENTITY,"PEER2"B) |> set identified

"inproc://example" |> connect identified

"ROUTER socket uses REQ's socket identity" |> s_send identified

s_dump sink

EXIT_SUCCESS

main ()

identity: Identity check in Felix

identity: Identity check in Go

//

// Demonstrate identities as used by the request-reply pattern. Run this

// program by itself.

//

package main

import (

"fmt"

zmq "github.com/alecthomas/gozmq"

)

func dump(sink *zmq.Socket) {

parts, err := sink.RecvMultipart(0)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

}

for _, msgdata := range parts {

is_text := true

fmt.Printf("[%03d] ", len(msgdata))

for _, char := range msgdata {

if char < 32 || char > 127 {

is_text = false

}

}

if is_text {

fmt.Printf("%s\n", msgdata)

} else {

fmt.Printf("%X\n", msgdata)

}

}

}

func main() {

context, _ := zmq.NewContext()

defer context.Close()

sink, err := context.NewSocket(zmq.ROUTER)

if err != nil {

print(err)

}

defer sink.Close()

sink.Bind("inproc://example")

// First allow 0MQ to set the identity

anonymous, err := context.NewSocket(zmq.REQ)

defer anonymous.Close()

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

}

anonymous.Connect("inproc://example")

err = anonymous.Send([]byte("ROUTER uses a generated 5 byte identity"), 0)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

}

dump(sink)

// Then set the identity ourselves

identified, err := context.NewSocket(zmq.REQ)

if err != nil {

print(err)

}

defer identified.Close()

identified.SetIdentity("PEER2")

identified.Connect("inproc://example")

identified.Send([]byte("ROUTER socket uses REQ's socket identity"), zmq.NOBLOCK)

dump(sink)

}

identity: Identity check in Haskell

{-# LANGUAGE OverloadedStrings #-}

module Main where

import System.ZMQ4.Monadic

import ZHelpers (dumpSock)

main :: IO ()

main =

runZMQ $ do

sink <- socket Router

bind sink "inproc://example"

anonymous <- socket Req

connect anonymous "inproc://example"

send anonymous [] "ROUTER uses a generated 5 byte identity"

dumpSock sink

identified <- socket Req

setIdentity (restrict "PEER2") identified

connect identified "inproc://example"

send identified [] "ROUTER socket uses REQ's socket identity"

dumpSock sink

identity: Identity check in Haxe

package ;

import ZHelpers;

import neko.Lib;

import neko.Sys;

import haxe.io.Bytes;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ;

import org.zeromq.ZContext;

import org.zeromq.ZFrame;

import org.zeromq.ZMQSocket;

/**

* Demonstrate identities as used by the request-reply pattern. Run this

* program by itself.

*/

class Identity

{

public static function main() {

var context:ZContext = new ZContext();

Lib.println("** Identity (see: http://zguide.zeromq.org/page:all#Request-Reply-Envelopes)");

// Socket facing clients

var sink:ZMQSocket = context.createSocket(ZMQ_ROUTER);

sink.bind("inproc://example");

// First allow 0MQ to set the identity

var anonymous:ZMQSocket = context.createSocket(ZMQ_REQ);

anonymous.connect("inproc://example");

anonymous.sendMsg(Bytes.ofString("ROUTER uses a generated 5 byte identity"));

ZHelpers.dump(sink);

// Then set the identity ourselves

var identified:ZMQSocket = context.createSocket(ZMQ_REQ);

identified.setsockopt(ZMQ_IDENTITY, Bytes.ofString("PEER2"));

identified.connect("inproc://example");

identified.sendMsg(Bytes.ofString("ROUTER socket uses REQ's socket identity"));

ZHelpers.dump(sink);

context.destroy();

}

}

identity: Identity check in Java

package guide;

import org.zeromq.SocketType;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ.Socket;

import org.zeromq.ZContext;

/**

* Demonstrate identities as used by the request-reply pattern.

*/

public class identity

{

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException

{

try (ZContext context = new ZContext()) {

Socket sink = context.createSocket(SocketType.ROUTER);

sink.bind("inproc://example");

// First allow 0MQ to set the identity, [00] + random 4byte

Socket anonymous = context.createSocket(SocketType.REQ);

anonymous.connect("inproc://example");

anonymous.send("ROUTER uses a generated UUID", 0);

ZHelper.dump(sink);

// Then set the identity ourself

Socket identified = context.createSocket(SocketType.REQ);

identified.setIdentity("PEER2".getBytes(ZMQ.CHARSET));

identified.connect("inproc://example");

identified.send("ROUTER socket uses REQ's socket identity", 0);

ZHelper.dump(sink);

}

}

}

identity: Identity check in Julia

identity: Identity check in Lua

--

-- Demonstrate identities as used by the request-reply pattern. Run this

-- program by itself. Note that the utility functions s_ are provided by

-- zhelpers.h. It gets boring for everyone to keep repeating this code.

--

-- Author: Robert G. Jakabosky <bobby@sharedrealm.com>

--

require"zmq"

require"zhelpers"

local context = zmq.init(1)

local sink = context:socket(zmq.ROUTER)

sink:bind("inproc://example")

-- First allow 0MQ to set the identity

local anonymous = context:socket(zmq.REQ)

anonymous:connect("inproc://example")

anonymous:send("ROUTER uses a generated 5 byte identity")

s_dump(sink)

-- Then set the identity ourselves

local identified = context:socket(zmq.REQ)

identified:setopt(zmq.IDENTITY, "PEER2")

identified:connect("inproc://example")

identified:send("ROUTER socket uses REQ's socket identity")

s_dump(sink)

sink:close()

anonymous:close()

identified:close()

context:term()

identity: Identity check in Node.js

// Demonstrate request-reply identities

var zmq = require('zeromq'),

zhelpers = require('./zhelpers');

var sink = zmq.socket("router");

sink.bind("inproc://example");

sink.on("message", zhelpers.dumpFrames);

// First allow 0MQ to set the identity

var anonymous = zmq.socket("req");

anonymous.connect("inproc://example");

anonymous.send("ROUTER uses generated 5 byte identity");

// Then set the identity ourselves

var identified = zmq.socket("req");

identified.identity = "PEER2";

identified.connect("inproc://example");

identified.send("ROUTER uses REQ's socket identity");

setTimeout(function() {

anonymous.close();

identified.close();

sink.close();

}, 250);

identity: Identity check in Objective-C

identity: Identity check in ooc

identity: Identity check in Perl

# Demonstrate request-reply identities in Perl

use strict;

use warnings;

use v5.10;

use ZMQ::FFI;

use ZMQ::FFI::Constants qw(ZMQ_ROUTER ZMQ_REQ ZMQ_IDENTITY);

use zhelpers;

my $context = ZMQ::FFI->new();

my $sink = $context->socket(ZMQ_ROUTER);

$sink->bind('inproc://example');

# First allow 0MQ to set the identity

my $anonymous = $context->socket(ZMQ_REQ);

$anonymous->connect('inproc://example');

$anonymous->send('ROUTER uses a generated 5 byte identity');

zhelpers::dump($sink);

# Then set the identity ourselves

my $identified = $context->socket(ZMQ_REQ);

$identified->set_identity('PEER2');

$identified->connect('inproc://example');

$identified->send("ROUTER socket uses REQ's socket identity");

zhelpers::dump($sink);

identity: Identity check in PHP

<?php

/*

* Demonstrate identities as used by the request-reply pattern. Run this

* program by itself. Note that the utility functions s_ are provided by

* zhelpers.h. It gets boring for everyone to keep repeating this code.

* @author Ian Barber <ian(dot)barber(at)gmail(dot)com>

*/

include 'zhelpers.php';

$context = new ZMQContext();

$sink = new ZMQSocket($context, ZMQ::SOCKET_ROUTER);

$sink->bind("inproc://example");

// First allow 0MQ to set the identity

$anonymous = new ZMQSocket($context, ZMQ::SOCKET_REQ);

$anonymous->connect("inproc://example");

$anonymous->send("ROUTER uses a generated 5 byte identity");

s_dump ($sink);

// Then set the identity ourselves

$identified = new ZMQSocket($context, ZMQ::SOCKET_REQ);

$identified->setSockOpt(ZMQ::SOCKOPT_IDENTITY, "PEER2");

$identified->connect("inproc://example");

$identified->send("ROUTER socket uses REQ's socket identity");

s_dump ($sink);

identity: Identity check in Python

# encoding: utf-8

#

# Demonstrate identities as used by the request-reply pattern. Run this

# program by itself.

#

# Author: Jeremy Avnet (brainsik) <spork(dash)zmq(at)theory(dot)org>

#

import zmq

import zhelpers

context = zmq.Context()

sink = context.socket(zmq.ROUTER)

sink.bind("inproc://example")

# First allow 0MQ to set the identity

anonymous = context.socket(zmq.REQ)

anonymous.connect("inproc://example")

anonymous.send(b"ROUTER uses a generated 5 byte identity")

zhelpers.dump(sink)

# Then set the identity ourselves

identified = context.socket(zmq.REQ)

identified.setsockopt(zmq.IDENTITY, b"PEER2")

identified.connect("inproc://example")

identified.send(b"ROUTER socket uses REQ's socket identity")

zhelpers.dump(sink)

identity: Identity check in Q

// Demonstrate identities as used by the request-reply pattern.

\l qzmq.q

ctx:zctx.new[]

sink:zsocket.new[ctx; zmq`ROUTER]

port:zsocket.bind[sink; `inproc://example]

// First allow 0MQ to set the identity

anonymous:zsocket.new[ctx; zmq`REQ]

zsocket.connect[anonymous; `inproc://example]

m0:zmsg.new[]

zmsg.push[m0; zframe.new["ROUTER uses a generated 5 byte identity"]]

zmsg.send[m0; anonymous]

zmsg.dump[zmsg.recv[sink]]

// Then set the identity ourselves

identified:zsocket.new[ctx; zmq`REQ]

zsockopt.set_identity[identified; "PEER2"]

zsocket.connect[identified; `inproc://example]

m1:zmsg.new[]

zmsg.push[m1; zframe.new["ROUTER socket users REQ's socket identity"]]

zmsg.send[m1; identified]

zmsg.dump[zmsg.recv[sink]]

zsocket.destroy[ctx; sink]

zsocket.destroy[ctx; anonymous]

zsocket.destroy[ctx; identified]

zctx.destroy[ctx]

\\

identity: Identity check in Racket

identity: Identity check in Ruby

identity: Identity check in Rust

identity: Identity check in Scala

identity: Identity check in Tcl

identity: Identity check in OCaml

Here is what the program prints:

----------------------------------------

[005] 006B8B4567

[000]

[039] ROUTER uses a generated 5 byte identity

----------------------------------------

[005] PEER2

[000]

[038] ROUTER uses REQ's socket identity

ROUTER Error Handling #

ROUTER sockets do have a somewhat brutal way of dealing with messages they can’t send anywhere: they drop them silently. It’s an attitude that makes sense in working code, but it makes debugging hard. The “send identity as first frame” approach is tricky enough that we often get this wrong when we’re learning, and the ROUTER’s stony silence when we mess up isn’t very constructive.

Since ZeroMQ v3.2 there’s a socket option you can set to catch this error: ZMQ_ROUTER_MANDATORY. Set that on the ROUTER socket and then when you provide an unroutable identity on a send call, the socket will signal an EHOSTUNREACH error.

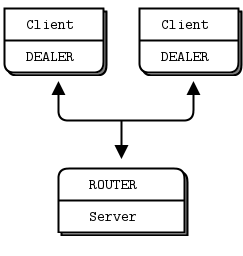

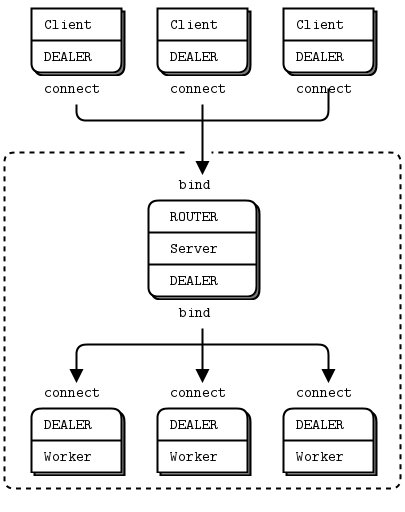

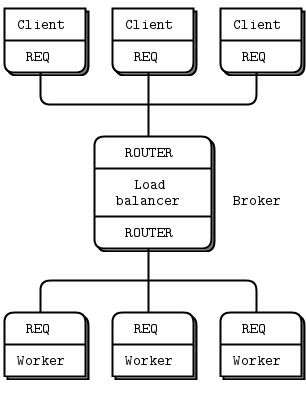

The Load Balancing Pattern #

Now let’s look at some code. We’ll see how to connect a ROUTER socket to a REQ socket, and then to a DEALER socket. These two examples follow the same logic, which is a load balancing pattern. This pattern is our first exposure to using the ROUTER socket for deliberate routing, rather than simply acting as a reply channel.

The load balancing pattern is very common and we’ll see it several times in this book. It solves the main problem with simple round robin routing (as PUSH and DEALER offer) which is that round robin becomes inefficient if tasks do not all roughly take the same time.

It’s the post office analogy. If you have one queue per counter, and you have some people buying stamps (a fast, simple transaction), and some people opening new accounts (a very slow transaction), then you will find stamp buyers getting unfairly stuck in queues. Just as in a post office, if your messaging architecture is unfair, people will get annoyed.

The solution in the post office is to create a single queue so that even if one or two counters get stuck with slow work, other counters will continue to serve clients on a first-come, first-serve basis.

One reason PUSH and DEALER use the simplistic approach is sheer performance. If you arrive in any major US airport, you’ll find long queues of people waiting at immigration. The border patrol officials will send people in advance to queue up at each counter, rather than using a single queue. Having people walk fifty yards in advance saves a minute or two per passenger. And because every passport check takes roughly the same time, it’s more or less fair. This is the strategy for PUSH and DEALER: send work loads ahead of time so that there is less travel distance.

This is a recurring theme with ZeroMQ: the world’s problems are diverse and you can benefit from solving different problems each in the right way. The airport isn’t the post office and one size fits no one, really well.

Let’s return to the scenario of a worker (DEALER or REQ) connected to a broker (ROUTER). The broker has to know when the worker is ready, and keep a list of workers so that it can take the least recently used worker each time.

The solution is really simple, in fact: workers send a “ready” message when they start, and after they finish each task. The broker reads these messages one-by-one. Each time it reads a message, it is from the last used worker. And because we’re using a ROUTER socket, we get an identity that we can then use to send a task back to the worker.

It’s a twist on request-reply because the task is sent with the reply, and any response for the task is sent as a new request. The following code examples should make it clearer.

ROUTER Broker and REQ Workers #

Here is an example of the load balancing pattern using a ROUTER broker talking to a set of REQ workers:

rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in Ada

rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in Basic

rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in C

// 2015-01-16T09:56+08:00

// ROUTER-to-REQ example

#include "zhelpers.h"

#include <pthread.h>

#define NBR_WORKERS 10

static void *

worker_task(void *args)

{

void *context = zmq_ctx_new();

void *worker = zmq_socket(context, ZMQ_REQ);

#if (defined (WIN32))

s_set_id(worker, (intptr_t)args);

#else

s_set_id(worker); // Set a printable identity.

#endif

zmq_connect(worker, "tcp://localhost:5671");

int total = 0;

while (1) {

// Tell the broker we're ready for work

s_send(worker, "Hi Boss");

// Get workload from broker, until finished

char *workload = s_recv(worker);

int finished = (strcmp(workload, "Fired!") == 0);

free(workload);

if (finished) {

printf("Completed: %d tasks\n", total);

break;

}

total++;

// Do some random work

s_sleep(randof(500) + 1);

}

zmq_close(worker);

zmq_ctx_destroy(context);

return NULL;

}

// .split main task

// While this example runs in a single process, that is only to make

// it easier to start and stop the example. Each thread has its own

// context and conceptually acts as a separate process.

int main(void)

{

void *context = zmq_ctx_new();

void *broker = zmq_socket(context, ZMQ_ROUTER);

zmq_bind(broker, "tcp://*:5671");

srandom((unsigned)time(NULL));

int worker_nbr;

for (worker_nbr = 0; worker_nbr < NBR_WORKERS; worker_nbr++) {

pthread_t worker;

pthread_create(&worker, NULL, worker_task, (void *)(intptr_t)worker_nbr);

}

// Run for five seconds and then tell workers to end

int64_t end_time = s_clock() + 5000;

int workers_fired = 0;

while (1) {

// Next message gives us least recently used worker

char *identity = s_recv(broker);

s_sendmore(broker, identity);

free(identity);

free(s_recv(broker)); // Envelope delimiter

free(s_recv(broker)); // Response from worker

s_sendmore(broker, "");

// Encourage workers until it's time to fire them

if (s_clock() < end_time)

s_send(broker, "Work harder");

else {

s_send(broker, "Fired!");

if (++workers_fired == NBR_WORKERS)

break;

}

}

zmq_close(broker);

zmq_ctx_destroy(context);

return 0;

}rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in C++

//

// Custom routing Router to Mama (ROUTER to REQ)

//

#include "zhelpers.hpp"

#include <thread>

#include <vector>

static void *

worker_thread(void *arg) {

zmq::context_t context(1);

zmq::socket_t worker(context, ZMQ_REQ);

// We use a string identity for ease here

#if (defined (WIN32))

s_set_id(worker, (intptr_t)arg);

worker.connect("tcp://localhost:5671"); // "ipc" doesn't yet work on windows.

#else

s_set_id(worker);

worker.connect("ipc://routing.ipc");

#endif

int total = 0;

while (1) {

// Tell the broker we're ready for work

s_send(worker, std::string("Hi Boss"));

// Get workload from broker, until finished

std::string workload = s_recv(worker);

if ("Fired!" == workload) {

std::cout << "Processed: " << total << " tasks" << std::endl;

break;

}

total++;

// Do some random work

s_sleep(within(500) + 1);

}

return NULL;

}

int main() {

zmq::context_t context(1);

zmq::socket_t broker(context, ZMQ_ROUTER);

#if (defined(WIN32))

broker.bind("tcp://*:5671"); // "ipc" doesn't yet work on windows.

#else

broker.bind("ipc://routing.ipc");

#endif

const int NBR_WORKERS = 10;

std::vector<std::thread> workers;

for (int worker_nbr = 0; worker_nbr < NBR_WORKERS; worker_nbr++) {

workers.push_back(std::move(std::thread(worker_thread, (void *)(intptr_t)worker_nbr)));

}

// Run for five seconds and then tell workers to end

int64_t end_time = s_clock() + 5000;

int workers_fired = 0;

while (1) {

// Next message gives us least recently used worker

std::string identity = s_recv(broker);

s_recv(broker); // Envelope delimiter

s_recv(broker); // Response from worker

s_sendmore(broker, identity);

s_sendmore(broker, std::string(""));

// Encourage workers until it's time to fire them

if (s_clock() < end_time)

s_send(broker, std::string("Work harder"));

else {

s_send(broker, std::string("Fired!"));

if (++workers_fired == NBR_WORKERS)

break;

}

}

for (int worker_nbr = 0; worker_nbr < NBR_WORKERS; worker_nbr++) {

workers[worker_nbr].join();

}

return 0;

}

rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in C#

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Diagnostics;

using System.Linq;

using System.Text;

using System.Threading;

using ZeroMQ;

namespace Examples

{

static partial class Program

{

static int RTReq_Workers = 10;

public static void RTReq(string[] args)

{

//

// ROUTER-to-REQ example

//

// While this example runs in a single process, that is only to make

// it easier to start and stop the example. Each thread has its own

// context and conceptually acts as a separate process.

//

// Author: metadings

//

using (var context = new ZContext())

using (var broker = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.ROUTER))

{

broker.Bind("tcp://*:5671");

for (int i = 0; i < RTReq_Workers; ++i)

{

int j = i; new Thread(() => RTReq_Worker(j)).Start();

}

var stopwatch = new Stopwatch();

stopwatch.Start();

// Run for five seconds and then tell workers to end

int workers_fired = 0;

while (true)

{

// Next message gives us least recently used worker

using (ZMessage identity = broker.ReceiveMessage())

{

broker.SendMore(identity[0]);

broker.SendMore(new ZFrame());

// Encourage workers until it's time to fire them

if (stopwatch.Elapsed < TimeSpan.FromSeconds(5))

{

broker.Send(new ZFrame("Work harder!"));

}

else

{

broker.Send(new ZFrame("Fired!"));

if (++workers_fired == RTReq_Workers)

{

break;

}

}

}

}

}

}

static void RTReq_Worker(int i)

{

using (var context = new ZContext())

using (var worker = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.REQ))

{

worker.IdentityString = "PEER" + i; // Set a printable identity

worker.Connect("tcp://127.0.0.1:5671");

int total = 0;

while (true)

{

// Tell the broker we're ready for work

worker.Send(new ZFrame("Hi Boss"));

// Get workload from broker, until finished

using (ZFrame frame = worker.ReceiveFrame())

{

bool finished = (frame.ReadString() == "Fired!");

if (finished)

{

break;

}

}

total++;

// Do some random work

Thread.Sleep(1);

}

Console.WriteLine("Completed: PEER{0}, {1} tasks", i, total);

}

}

}

}

rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in CL

;;; -*- Mode:Lisp; Syntax:ANSI-Common-Lisp; -*-

;;;

;;; Custom routing Router to Mama (ROUTER to REQ) in Common Lisp

;;;

;;; Kamil Shakirov <kamils80@gmail.com>

;;;

(defpackage #:zguide.rtmama

(:nicknames #:rtmama)

(:use #:cl #:zhelpers)

(:export #:main))

(in-package :zguide.rtmama)

(defparameter *number-workers* 10)

(defun worker-thread (context)

(zmq:with-socket (worker context zmq:req)

;; We use a string identity for ease here

(set-socket-id worker)

(zmq:connect worker "ipc://routing.ipc")

(let ((total 0))

(loop

;; Tell the router we're ready for work

(send-text worker "ready")

;; Get workload from router, until finished

(let ((workload (recv-text worker)))

(when (string= workload "END")

(message "Processed: ~D tasks~%" total)

(return))

(incf total))

;; Do some random work

(isys:usleep (within 100000))))))

(defun main ()

(zmq:with-context (context 1)

(zmq:with-socket (client context zmq:router)

(zmq:bind client "ipc://routing.ipc")

(dotimes (i *number-workers*)

(bt:make-thread (lambda () (worker-thread context))

:name (format nil "worker-thread-~D" i)))

(loop :repeat (* 10 *number-workers*) :do

;; LRU worker is next waiting in queue

(let ((address (recv-text client)))

(recv-text client) ; empty

(recv-text client) ; ready

(send-more-text client address)

(send-more-text client "")

(send-text client "This is the workload")))

;; Now ask mamas to shut down and report their results

(loop :repeat *number-workers* :do

;; LRU worker is next waiting in queue

(let ((address (recv-text client)))

(recv-text client) ; empty

(recv-text client) ; ready

(send-more-text client address)

(send-more-text client "")

(send-text client "END")))

;; Give 0MQ/2.0.x time to flush output

(sleep 1)))

(cleanup))

rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in Delphi

program rtreq;

//

// ROUTER-to-REQ example

// @author Varga Balazs <bb.varga@gmail.com>

//

{$APPTYPE CONSOLE}

uses

SysUtils

, Windows

, zmqapi

, zhelpers

;

const

NBR_WORKERS = 10;

procedure worker_task( args: Pointer );

var

context: TZMQContext;

worker: TZMQSocket;

total: Integer;

workload: Utf8String;

begin

context := TZMQContext.create;

worker := context.Socket( stReq );

s_set_id( worker ); // Set a printable identity

worker.connect( 'tcp://localhost:5671' );

total := 0;

while true do

begin

// Tell the broker we're ready for work

worker.send( 'Hi Boss' );

// Get workload from broker, until finished

worker.recv( workload );

if workload = 'Fired!' then

begin

zNote( Format( 'Completed: %d tasks', [total] ) );

break;

end;

Inc( total );

// Do some random work

sleep( random( 500 ) + 1 );

end;

worker.Free;

context.Free;

end;

// While this example runs in a single process, that is just to make

// it easier to start and stop the example. Each thread has its own

// context and conceptually acts as a separate process.

var

context: TZMQContext;

broker: TZMQSocket;

i,

workers_fired: Integer;

tid: Cardinal;

identity,

s: Utf8String;

fFrequency,

fstart,

fStop,

dt: Int64;

begin

context := TZMQContext.create;

broker := context.Socket( stRouter );

broker.bind( 'tcp://*:5671' );

Randomize;

for i := 0 to NBR_WORKERS - 1 do

BeginThread( nil, 0, @worker_task, nil, 0, tid );

// Start our clock now

QueryPerformanceFrequency( fFrequency );

QueryPerformanceCounter( fStart );

// Run for five seconds and then tell workers to end

workers_fired := 0;

while true do

begin

// Next message gives us least recently used worker

broker.recv( identity );

broker.send( identity, [sfSndMore] );

broker.recv( s ); // Envelope delimiter

broker.recv( s ); // Response from worker

broker.send( '', [sfSndMore] );

QueryPerformanceCounter( fStop );

dt := ( MSecsPerSec * ( fStop - fStart ) ) div fFrequency;

if dt < 5000 then

broker.send( 'Work harder' )

else begin

broker.send( 'Fired!' );

Inc( workers_fired );

if workers_fired = NBR_WORKERS then

break;

end;

end;

broker.Free;

context.Free;

end.

rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in Erlang

#! /usr/bin/env escript

%%

%% Custom routing Router to Mama (ROUTER to REQ)

%%

%% While this example runs in a single process, that is just to make

%% it easier to start and stop the example. Each thread has its own

%% context and conceptually acts as a separate process.

%%

-define(NBR_WORKERS, 10).

worker_task() ->

random:seed(now()),

{ok, Context} = erlzmq:context(),

{ok, Worker} = erlzmq:socket(Context, req),

%% We use a string identity for ease here

ok = erlzmq:setsockopt(Worker, identity, pid_to_list(self())),

ok = erlzmq:connect(Worker, "ipc://routing.ipc"),

Total = handle_tasks(Worker, 0),

io:format("Processed ~b tasks~n", [Total]),

erlzmq:close(Worker),

erlzmq:term(Context).

handle_tasks(Worker, TaskCount) ->

%% Tell the router we're ready for work

ok = erlzmq:send(Worker, <<"ready">>),

%% Get workload from router, until finished

case erlzmq:recv(Worker) of

{ok, <<"END">>} -> TaskCount;

{ok, _} ->

%% Do some random work

timer:sleep(random:uniform(1000) + 1),

handle_tasks(Worker, TaskCount + 1)

end.

main(_) ->

{ok, Context} = erlzmq:context(),

{ok, Client} = erlzmq:socket(Context, router),

ok = erlzmq:bind(Client, "ipc://routing.ipc"),

start_workers(?NBR_WORKERS),

route_work(Client, ?NBR_WORKERS * 10),

stop_workers(Client, ?NBR_WORKERS),

ok = erlzmq:close(Client),

ok = erlzmq:term(Context).

start_workers(0) -> ok;

start_workers(N) when N > 0 ->

spawn(fun() -> worker_task() end),

start_workers(N - 1).

route_work(_Client, 0) -> ok;

route_work(Client, N) when N > 0 ->

%% LRU worker is next waiting in queue

{ok, Address} = erlzmq:recv(Client),

{ok, <<>>} = erlzmq:recv(Client),

{ok, <<"ready">>} = erlzmq:recv(Client),

ok = erlzmq:send(Client, Address, [sndmore]),

ok = erlzmq:send(Client, <<>>, [sndmore]),

ok = erlzmq:send(Client, <<"This is the workload">>),

route_work(Client, N - 1).

stop_workers(_Client, 0) -> ok;

stop_workers(Client, N) ->

%% Ask mama to shut down and report their results

{ok, Address} = erlzmq:recv(Client),

{ok, <<>>} = erlzmq:recv(Client),

{ok, _Ready} = erlzmq:recv(Client),

ok = erlzmq:send(Client, Address, [sndmore]),

ok = erlzmq:send(Client, <<>>, [sndmore]),

ok = erlzmq:send(Client, <<"END">>),

stop_workers(Client, N - 1).

rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in Elixir

defmodule Rtreq do

@moduledoc """

Generated by erl2ex (http://github.com/dazuma/erl2ex)

From Erlang source: (Unknown source file)

At: 2019-12-20 13:57:33

"""

defmacrop erlconst_NBR_WORKERS() do

quote do

10

end

end

def worker_task() do

:random.seed(:erlang.now())

{:ok, context} = :erlzmq.context()

{:ok, worker} = :erlzmq.socket(context, :req)

:ok = :erlzmq.setsockopt(worker, :identity, :erlang.pid_to_list(self()))

:ok = :erlzmq.connect(worker, 'ipc://routing.ipc')

total = handle_tasks(worker, 0)

:io.format('Processed ~b tasks~n', [total])

:erlzmq.close(worker)

:erlzmq.term(context)

end

def handle_tasks(worker, taskCount) do

:ok = :erlzmq.send(worker, "ready")

case(:erlzmq.recv(worker)) do

{:ok, "END"} ->

taskCount

{:ok, _} ->

:timer.sleep(:random.uniform(1000) + 1)

handle_tasks(worker, taskCount + 1)

end

end

def main() do

{:ok, context} = :erlzmq.context()

{:ok, client} = :erlzmq.socket(context, :router)

:ok = :erlzmq.bind(client, 'ipc://routing.ipc')

start_workers(erlconst_NBR_WORKERS())

route_work(client, erlconst_NBR_WORKERS() * 10)

stop_workers(client, erlconst_NBR_WORKERS())

:ok = :erlzmq.close(client)

:ok = :erlzmq.term(context)

end

def start_workers(0) do

:ok

end

def start_workers(n) when n > 0 do

:erlang.spawn(fn -> worker_task() end)

start_workers(n - 1)

end

def route_work(_client, 0) do

:ok

end

def route_work(client, n) when n > 0 do

{:ok, address} = :erlzmq.recv(client)

{:ok, <<>>} = :erlzmq.recv(client)

{:ok, "ready"} = :erlzmq.recv(client)

:ok = :erlzmq.send(client, address, [:sndmore])

:ok = :erlzmq.send(client, <<>>, [:sndmore])

:ok = :erlzmq.send(client, "This is the workload")

route_work(client, n - 1)

end

def stop_workers(_client, 0) do

:ok

end

def stop_workers(client, n) do

{:ok, address} = :erlzmq.recv(client)

{:ok, <<>>} = :erlzmq.recv(client)

{:ok, _ready} = :erlzmq.recv(client)

:ok = :erlzmq.send(client, address, [:sndmore])

:ok = :erlzmq.send(client, <<>>, [:sndmore])

:ok = :erlzmq.send(client, "END")

stop_workers(client, n - 1)

end

end

Rtreq.main

rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in F#

(*

Custom routing Router to Mama (ROUTER to REQ)

While this example runs in a single process, that is just to make

it easier to start and stop the example. Each thread has its own

context and conceptually acts as a separate process.

*)

#r @"bin/fszmq.dll"

open fszmq

open fszmq.Context

open fszmq.Socket

#load "zhelpers.fs"

open System.Threading

let [<Literal>] NBR_WORKERS = 10

let rand = srandom()

let worker_task () =

use context = new Context(1)

use worker = req context

// we use a string identity for ease here

s_setID worker

"tcp://localhost:5571" |> connect worker

let workerID = ZMQ.IDENTITY |> get worker |> decode

let rec loop total =

// tell the router we're ready for work

"ready"B |>> worker

// get workload from router, until finished

let workload = s_recv worker

if workload = "END"

then printfn' "(%s) Processed: %d tasks" workerID total

else // do some random work

sleep (rand.Next(0,1000) + 1)

loop (total + 1)

loop 0

let main () =

use context = new Context(1)

use client = route context

"tcp://*:5571" |> bind client

for _ in 1 .. NBR_WORKERS do

let worker = Thread(ThreadStart(worker_task))

worker.Start()

for _ in 1 .. (NBR_WORKERS * 10) do

// LRU worker is next waiting in queue

let address = recv client

recv client |> ignore // empty

recv client |> ignore // ready

client <~| address

<~| ""B

<<| "This is the workload"B

// now ask the mamas to shut down and report their results

for _ in 1 .. NBR_WORKERS do

let address = recv client

recv client |> ignore // empty

recv client |> ignore // ready

client <~| address

<~| ""B

<<| "END"B

EXIT_SUCCESS

main ()

rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in Felix

rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in Go

//

// ROUTER-to-REQ example

//

package main

import (

"fmt"

zmq "github.com/alecthomas/gozmq"

"math/rand"

"strings"

"time"

)

const NBR_WORKERS = 10

func randomString() string {

source := "abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz"

target := make([]string, 20)

for i := 0; i < 20; i++ {

target[i] = string(source[rand.Intn(len(source))])

}

return strings.Join(target, "")

}

func workerTask() {

context, _ := zmq.NewContext()

defer context.Close()

worker, _ := context.NewSocket(zmq.REQ)

worker.SetIdentity(randomString())

worker.Connect("tcp://localhost:5671")

defer worker.Close()

total := 0

for {

err := worker.Send([]byte("Hi Boss"), 0)

if err != nil {

print(err)

}

workload, _ := worker.Recv(0)

if string(workload) == "Fired!" {

id, _ := worker.Identity()

fmt.Printf("Completed: %d tasks (%s)\n", total, id)

break

}

total += 1

msec := rand.Intn(1000)

time.Sleep(time.Duration(msec) * time.Millisecond)

}

}

// While this example runs in a single process, that is just to make

// it easier to start and stop the example. Each goroutine has its own

// context and conceptually acts as a separate process.

func main() {

context, _ := zmq.NewContext()

defer context.Close()

broker, _ := context.NewSocket(zmq.ROUTER)

defer broker.Close()

broker.Bind("tcp://*:5671")

rand.Seed(time.Now().Unix())

for i := 0; i < NBR_WORKERS; i++ {

go workerTask()

}

end_time := time.Now().Unix() + 5

workers_fired := 0

for {

// Next message gives us least recently used worker

parts, err := broker.RecvMultipart(0)

if err != nil {

print(err)

}

identity := parts[0]

now := time.Now().Unix()

if now < end_time {

broker.SendMultipart([][]byte{identity, []byte(""), []byte("Work harder")}, 0)

} else {

broker.SendMultipart([][]byte{identity, []byte(""), []byte("Fired!")}, 0)

workers_fired++

if workers_fired == NBR_WORKERS {

break

}

}

}

}

rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in Haskell

{-# LANGUAGE OverloadedStrings #-}

-- |

-- Router broker and REQ workers (p.92)

module Main where

import System.ZMQ4.Monadic

import Control.Concurrent (threadDelay, forkIO)

import Control.Concurrent.MVar (withMVar, newMVar, MVar)

import Data.ByteString.Char8 (unpack)

import Control.Monad (replicateM_, unless)

import ZHelpers (setRandomIdentity)

import Text.Printf

import Data.Time.Clock (diffUTCTime, getCurrentTime, UTCTime)

import System.Random

nbrWorkers :: Int

nbrWorkers = 10

-- In general, although locks are an antipattern in ZeroMQ, we need a lock

-- for the stdout handle, otherwise we will get jumbled text. We don't

-- use the lock for anything zeroMQ related, just output to screen.

workerThread :: MVar () -> IO ()

workerThread lock =

runZMQ $ do

worker <- socket Req

setRandomIdentity worker

connect worker "ipc://routing.ipc"

work worker

where

work = loop 0 where

loop val sock = do

send sock [] "ready"

workload <- receive sock

if unpack workload == "Fired!"

then liftIO $ withMVar lock $ \_ -> printf "Completed: %d tasks\n" (val::Int)

else do

rand <- liftIO $ getStdRandom (randomR (500::Int, 5000))

liftIO $ threadDelay rand

loop (val+1) sock

main :: IO ()

main =

runZMQ $ do

client <- socket Router

bind client "ipc://routing.ipc"

-- We only need MVar for printing the output (so output doesn't become interleaved)

-- The alternative is to Make an ipc channel, but that distracts from the example

-- or to 'NoBuffering' 'stdin'

lock <- liftIO $ newMVar ()

liftIO $ replicateM_ nbrWorkers (forkIO $ workerThread lock)

start <- liftIO getCurrentTime

clientTask client start

-- You need to give some time to the workers so they can exit properly

liftIO $ threadDelay $ 1 * 1000 * 1000

where

clientTask :: Socket z Router -> UTCTime -> ZMQ z ()

clientTask = loop nbrWorkers where

loop c sock start = unless (c <= 0) $ do

-- Next message is the leaset recently used worker

ident <- receive sock

send sock [SendMore] ident

-- Envelope delimiter

receive sock

-- Ready signal from worker

receive sock

-- Send delimiter

send sock [SendMore] ""

-- Send Work unless time is up

now <- liftIO getCurrentTime

if c /= nbrWorkers || diffUTCTime now start > 5

then do

send sock [] "Fired!"

loop (c-1) sock start

else do

send sock [] "Work harder"

loop c sock startrtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in Haxe

package ;

import haxe.io.Bytes;

import neko.Lib;

import neko.Sys;

#if (neko || cpp)

import neko.vm.Thread;

#end

import org.zeromq.ZFrame;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ;

import org.zeromq.ZContext;

import org.zeromq.ZMQSocket;

import ZHelpers;

/**

* Custom routing Router to Mama (ROUTER to REQ)

*

* While this example runs in a single process (for cpp & neko), that is just

* to make it easier to start and stop the example. Each thread has its own

* context and conceptually acts as a separate process.

*

* See: http://zguide.zeromq.org/page:all#Least-Recently-Used-Routing-LRU-Pattern

*/

class RTMama

{

private static inline var NBR_WORKERS = 10;

public static function workerTask() {

var context:ZContext = new ZContext();

var worker:ZMQSocket = context.createSocket(ZMQ_REQ);

// Use a random string identity for ease here

var id = ZHelpers.setID(worker);

worker.connect("ipc:///tmp/routing.ipc");

var total = 0;

while (true) {

// Tell the router we are ready

ZFrame.newStringFrame("ready").send(worker);

// Get workload from router, until finished

var workload:ZFrame = ZFrame.recvFrame(worker);

if (workload == null) break;

if (workload.streq("END")) {

Lib.println("Processed: " + total + " tasks");

break;

}

total++;

// Do some random work

Sys.sleep((ZHelpers.randof(1000) + 1) / 1000.0);

}

context.destroy();

}

public static function main() {

Lib.println("** RTMama (see: http://zguide.zeromq.org/page:all#Least-Recently-Used-Routing-LRU-Pattern)");

// Implementation note: Had to move php forking before main thread ZMQ Context creation to

// get the main thread to receive messages from the child processes.

for (worker_nbr in 0 ... NBR_WORKERS) {

#if php

forkWorkerTask();

#else

Thread.create(workerTask);

#end

}

var context:ZContext = new ZContext();

var client:ZMQSocket = context.createSocket(ZMQ_ROUTER);

// Implementation note: Had to add the /tmp prefix to get this to work on Linux Ubuntu 10

client.bind("ipc:///tmp/routing.ipc");

Sys.sleep(1);

for (task_nbr in 0 ... NBR_WORKERS * 10) {

// LRU worker is next waiting in queue

var address:ZFrame = ZFrame.recvFrame(client);

var empty:ZFrame = ZFrame.recvFrame(client);

var ready:ZFrame = ZFrame.recvFrame(client);

address.send(client, ZFrame.ZFRAME_MORE);

ZFrame.newStringFrame("").send(client, ZFrame.ZFRAME_MORE);

ZFrame.newStringFrame("This is the workload").send(client);

}

// Now ask mamas to shut down and report their results

for (worker_nbr in 0 ... NBR_WORKERS) {

var address:ZFrame = ZFrame.recvFrame(client);

var empty:ZFrame = ZFrame.recvFrame(client);

var ready:ZFrame = ZFrame.recvFrame(client);

address.send(client, ZFrame.ZFRAME_MORE);

ZFrame.newStringFrame("").send(client, ZFrame.ZFRAME_MORE);

ZFrame.newStringFrame("END").send(client);

}

context.destroy();

}

#if php

private static inline function forkWorkerTask() {

untyped __php__('

$pid = pcntl_fork();

if ($pid == 0) {

RTMama::workerTask();

exit();

}');

return;

}

#end

}rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in Java

package guide;

import java.util.Random;

import org.zeromq.SocketType;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ.Socket;

import org.zeromq.ZContext;

/**

* ROUTER-TO-REQ example

*/

public class rtreq

{

private static Random rand = new Random();

private static final int NBR_WORKERS = 10;

private static class Worker extends Thread

{

@Override

public void run()

{

try (ZContext context = new ZContext()) {

Socket worker = context.createSocket(SocketType.REQ);

ZHelper.setId(worker); // Set a printable identity

worker.connect("tcp://localhost:5671");

int total = 0;

while (true) {

// Tell the broker we're ready for work

worker.send("Hi Boss");

// Get workload from broker, until finished

String workload = worker.recvStr();

boolean finished = workload.equals("Fired!");

if (finished) {

System.out.printf("Completed: %d tasks\n", total);

break;

}

total++;

// Do some random work

try {

Thread.sleep(rand.nextInt(500) + 1);

}

catch (InterruptedException e) {

}

}

}

}

}

/**

* While this example runs in a single process, that is just to make

* it easier to start and stop the example. Each thread has its own

* context and conceptually acts as a separate process.

*/

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception

{

try (ZContext context = new ZContext()) {

Socket broker = context.createSocket(SocketType.ROUTER);

broker.bind("tcp://*:5671");

for (int workerNbr = 0; workerNbr < NBR_WORKERS; workerNbr++) {

Thread worker = new Worker();

worker.start();

}

// Run for five seconds and then tell workers to end

long endTime = System.currentTimeMillis() + 5000;

int workersFired = 0;

while (true) {

// Next message gives us least recently used worker

String identity = broker.recvStr();

broker.sendMore(identity);

broker.recvStr(); // Envelope delimiter

broker.recvStr(); // Response from worker

broker.sendMore("");

// Encourage workers until it's time to fire them

if (System.currentTimeMillis() < endTime)

broker.send("Work harder");

else {

broker.send("Fired!");

if (++workersFired == NBR_WORKERS)

break;

}

}

}

}

}

rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in Julia

rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in Lua

--

-- Custom routing Router to Mama (ROUTER to REQ)

--

-- While this example runs in a single process, that is just to make

-- it easier to start and stop the example. Each thread has its own

-- context and conceptually acts as a separate process.

--

-- Author: Robert G. Jakabosky <bobby@sharedrealm.com>

--

require"zmq"

require"zmq.threads"

require"zhelpers"

NBR_WORKERS = 10

local pre_code = [[

local identity, seed = ...

local zmq = require"zmq"

require"zhelpers"

math.randomseed(seed)

]]

local worker_task = pre_code .. [[

local context = zmq.init(1)

local worker = context:socket(zmq.REQ)

-- We use a string identity for ease here

worker:setopt(zmq.IDENTITY, identity)

worker:connect("ipc://routing.ipc")

local total = 0

while true do

-- Tell the router we're ready for work

worker:send("ready")

-- Get workload from router, until finished

local workload = worker:recv()

local finished = (workload == "END")

if (finished) then

printf ("Processed: %d tasks\n", total)

break

end

total = total + 1

-- Do some random work

s_sleep (randof (1000) + 1)

end

worker:close()

context:term()

]]

s_version_assert (2, 1)

local context = zmq.init(1)

local client = context:socket(zmq.ROUTER)

client:bind("ipc://routing.ipc")

math.randomseed(os.time())

local workers = {}

for n=1,NBR_WORKERS do

local identity = string.format("%04X-%04X", randof (0x10000), randof (0x10000))

local seed = os.time() + math.random()

workers[n] = zmq.threads.runstring(context, worker_task, identity, seed)

workers[n]:start()

end

for n=1,(NBR_WORKERS * 10) do

-- LRU worker is next waiting in queue

local address = client:recv()

local empty = client:recv()

local ready = client:recv()

client:send(address, zmq.SNDMORE)

client:send("", zmq.SNDMORE)

client:send("This is the workload")

end

-- Now ask mamas to shut down and report their results

for n=1,NBR_WORKERS do

local address = client:recv()

local empty = client:recv()

local ready = client:recv()

client:send(address, zmq.SNDMORE)

client:send("", zmq.SNDMORE)

client:send("END")

end

for n=1,NBR_WORKERS do

assert(workers[n]:join())

end

client:close()

context:term()

rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in Node.js

var zmq = require('zeromq');

var WORKERS_NUM = 10;

var router = zmq.socket('router');

var d = new Date();

var endTime = d.getTime() + 5000;

router.bindSync('tcp://*:9000');

router.on('message', function () {

// get the identity of current worker

var identity = Array.prototype.slice.call(arguments)[0];

var d = new Date();

var time = d.getTime();

if (time < endTime) {

router.send([identity, '', 'Work harder!'])

} else {

router.send([identity, '', 'Fired!']);

}

});

// To keep it simple we going to use

// workers in closures and tcp instead of

// node clusters and threads

for (var i = 0; i < WORKERS_NUM; i++) {

(function () {

var worker = zmq.socket('req');

worker.connect('tcp://127.0.0.1:9000');

var total = 0;

worker.on('message', function (msg) {

var message = msg.toString();

if (message === 'Fired!'){

console.log('Completed %d tasks', total);

worker.close();

}

total++;

setTimeout(function () {

worker.send('Hi boss!');

}, 1000)

});

worker.send('Hi boss!');

})();

}

rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in Objective-C

rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in ooc

rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in Perl

# ROUTER-to-REQ in Perl

use strict;

use warnings;

use v5.10;

use threads;

use Time::HiRes qw(usleep);

use ZMQ::FFI;

use ZMQ::FFI::Constants qw(ZMQ_REQ ZMQ_ROUTER);

my $NBR_WORKERS = 10;

sub worker_task {

my $context = ZMQ::FFI->new();

my $worker = $context->socket(ZMQ_REQ);

$worker->set_identity(Time::HiRes::time());

$worker->connect('tcp://localhost:5671');

my $total = 0;

WORKER_LOOP:

while (1) {

# Tell the broker we're ready for work

$worker->send('Hi Boss');

# Get workload from broker, until finished

my $workload = $worker->recv();

my $finished = $workload eq "Fired!";

if ($finished) {

say "Completed $total tasks";

last WORKER_LOOP;

}

$total++;

# Do some random work

usleep int(rand(500_000)) + 1;

}

}

# While this example runs in a single process, that is only to make

# it easier to start and stop the example. Each thread has its own

# context and conceptually acts as a separate process.

my $context = ZMQ::FFI->new();

my $broker = $context->socket(ZMQ_ROUTER);

$broker->bind('tcp://*:5671');

for my $worker_nbr (1..$NBR_WORKERS) {

threads->create('worker_task')->detach();

}

# Run for five seconds and then tell workers to end

my $end_time = time() + 5;

my $workers_fired = 0;

BROKER_LOOP:

while (1) {

# Next message gives us least recently used worker

my ($identity, $delimiter, $response) = $broker->recv_multipart();

# Encourage workers until it's time to fire them

if ( time() < $end_time ) {

$broker->send_multipart([$identity, '', 'Work harder']);

}

else {

$broker->send_multipart([$identity, '', 'Fired!']);

if ( ++$workers_fired == $NBR_WORKERS) {

last BROKER_LOOP;

}

}

}

rtreq: ROUTER-to-REQ in PHP

<?php

/*

* Custom routing Router to Mama (ROUTER to REQ)

* @author Ian Barber <ian(dot)barber(at)gmail(dot)com>a

*/

define("NBR_WORKERS", 10);

function worker_thread()

{

$context = new ZMQContext();