Chapter 4 - Reliable Request-Reply Patterns #

Chapter 3 - Advanced Request-Reply Patterns covered advanced uses of ZeroMQ’s request-reply pattern with working examples. This chapter looks at the general question of reliability and builds a set of reliable messaging patterns on top of ZeroMQ’s core request-reply pattern.

In this chapter, we focus heavily on user-space request-reply patterns, reusable models that help you design your own ZeroMQ architectures:

- The Lazy Pirate pattern: reliable request-reply from the client side

- The Simple Pirate pattern: reliable request-reply using load balancing

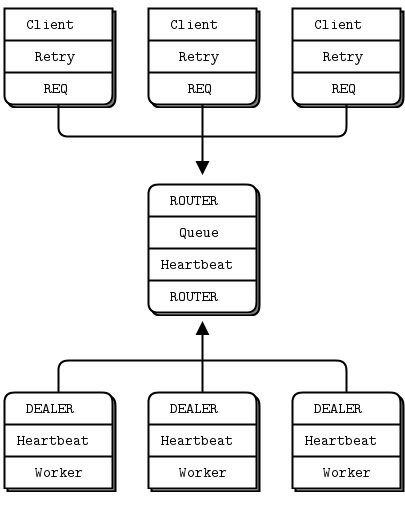

- The Paranoid Pirate pattern: reliable request-reply with heartbeating

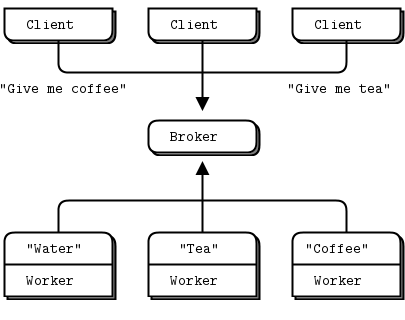

- The Majordomo pattern: service-oriented reliable queuing

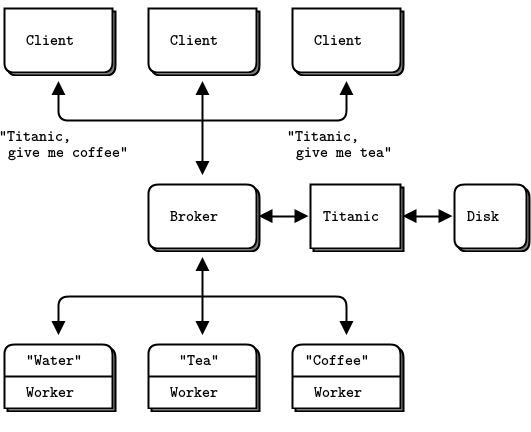

- The Titanic pattern: disk-based/disconnected reliable queuing

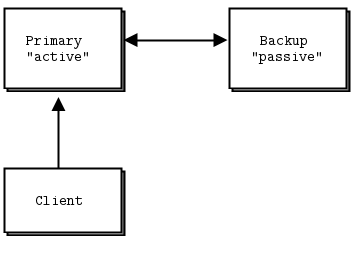

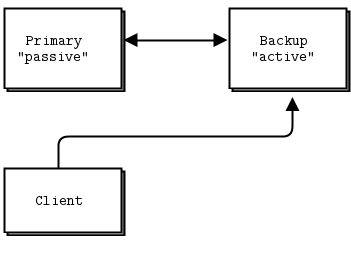

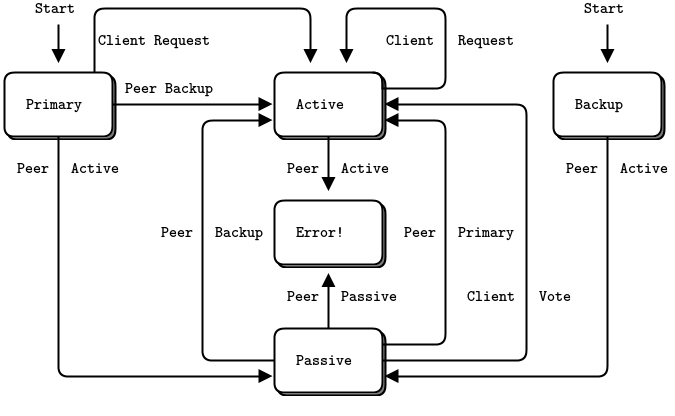

- The Binary Star pattern: primary-backup server failover

- The Freelance pattern: brokerless reliable request-reply

What is “Reliability”? #

Most people who speak of “reliability” don’t really know what they mean. We can only define reliability in terms of failure. That is, if we can handle a certain set of well-defined and understood failures, then we are reliable with respect to those failures. No more, no less. So let’s look at the possible causes of failure in a distributed ZeroMQ application, in roughly descending order of probability:

-

Application code is the worst offender. It can crash and exit, freeze and stop responding to input, run too slowly for its input, exhaust all memory, and so on.

-

System code–such as brokers we write using ZeroMQ–can die for the same reasons as application code. System code should be more reliable than application code, but it can still crash and burn, and especially run out of memory if it tries to queue messages for slow clients.

-

Message queues can overflow, typically in system code that has learned to deal brutally with slow clients. When a queue overflows, it starts to discard messages. So we get “lost” messages.

-

Networks can fail (e.g., WiFi gets switched off or goes out of range). ZeroMQ will automatically reconnect in such cases, but in the meantime, messages may get lost.

-

Hardware can fail and take with it all the processes running on that box.

-

Networks can fail in exotic ways, e.g., some ports on a switch may die and those parts of the network become inaccessible.

-

Entire data centers can be struck by lightning, earthquakes, fire, or more mundane power or cooling failures.

To make a software system fully reliable against all of these possible failures is an enormously difficult and expensive job and goes beyond the scope of this book.

Because the first five cases in the above list cover 99.9% of real world requirements outside large companies (according to a highly scientific study I just ran, which also told me that 78% of statistics are made up on the spot, and moreover never to trust a statistic that we didn’t falsify ourselves), that’s what we’ll examine. If you’re a large company with money to spend on the last two cases, contact my company immediately! There’s a large hole behind my beach house waiting to be converted into an executive swimming pool.

Designing Reliability #

So to make things brutally simple, reliability is “keeping things working properly when code freezes or crashes”, a situation we’ll shorten to “dies”. However, the things we want to keep working properly are more complex than just messages. We need to take each core ZeroMQ messaging pattern and see how to make it work (if we can) even when code dies.

Let’s take them one-by-one:

-

Request-reply: if the server dies (while processing a request), the client can figure that out because it won’t get an answer back. Then it can give up in a huff, wait and try again later, find another server, and so on. As for the client dying, we can brush that off as “someone else’s problem” for now.

-

Pub-sub: if the client dies (having gotten some data), the server doesn’t know about it. Pub-sub doesn’t send any information back from client to server. But the client can contact the server out-of-band, e.g., via request-reply, and ask, “please resend everything I missed”. As for the server dying, that’s out of scope for here. Subscribers can also self-verify that they’re not running too slowly, and take action (e.g., warn the operator and die) if they are.

-

Pipeline: if a worker dies (while working), the ventilator doesn’t know about it. Pipelines, like the grinding gears of time, only work in one direction. But the downstream collector can detect that one task didn’t get done, and send a message back to the ventilator saying, “hey, resend task 324!” If the ventilator or collector dies, whatever upstream client originally sent the work batch can get tired of waiting and resend the whole lot. It’s not elegant, but system code should really not die often enough to matter.

In this chapter we’ll focus just on request-reply, which is the low-hanging fruit of reliable messaging.

The basic request-reply pattern (a REQ client socket doing a blocking send/receive to a REP server socket) scores low on handling the most common types of failure. If the server crashes while processing the request, the client just hangs forever. If the network loses the request or the reply, the client hangs forever.

Request-reply is still much better than TCP, thanks to ZeroMQ’s ability to reconnect peers silently, to load balance messages, and so on. But it’s still not good enough for real work. The only case where you can really trust the basic request-reply pattern is between two threads in the same process where there’s no network or separate server process to die.

However, with a little extra work, this humble pattern becomes a good basis for real work across a distributed network, and we get a set of reliable request-reply (RRR) patterns that I like to call the Pirate patterns (you’ll eventually get the joke, I hope).

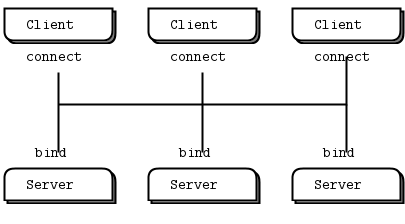

There are, in my experience, roughly three ways to connect clients to servers. Each needs a specific approach to reliability:

-

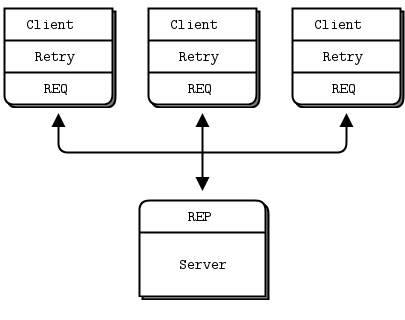

Multiple clients talking directly to a single server. Use case: a single well-known server to which clients need to talk. Types of failure we aim to handle: server crashes and restarts, and network disconnects.

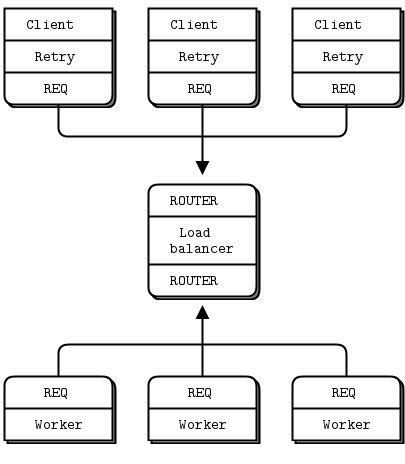

-

Multiple clients talking to a broker proxy that distributes work to multiple workers. Use case: service-oriented transaction processing. Types of failure we aim to handle: worker crashes and restarts, worker busy looping, worker overload, queue crashes and restarts, and network disconnects.

-

Multiple clients talking to multiple servers with no intermediary proxies. Use case: distributed services such as name resolution. Types of failure we aim to handle: service crashes and restarts, service busy looping, service overload, and network disconnects.

Each of these approaches has its trade-offs and often you’ll mix them. We’ll look at all three in detail.

Client-Side Reliability (Lazy Pirate Pattern) #

We can get very simple reliable request-reply with some changes to the client. We call this the Lazy Pirate pattern. Rather than doing a blocking receive, we:

- Poll the REQ socket and receive from it only when it’s sure a reply has arrived.

- Resend a request, if no reply has arrived within a timeout period.

- Abandon the transaction if there is still no reply after several requests.

If you try to use a REQ socket in anything other than a strict send/receive fashion, you’ll get an error (technically, the REQ socket implements a small finite-state machine to enforce the send/receive ping-pong, and so the error code is called “EFSM”). This is slightly annoying when we want to use REQ in a pirate pattern, because we may send several requests before getting a reply.

The pretty good brute force solution is to close and reopen the REQ socket after an error:

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Ada

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Basic

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in C

#include <czmq.h>

#define REQUEST_TIMEOUT 2500 // msecs, (>1000!)

#define REQUEST_RETRIES 3 // Before we abandon

#define SERVER_ENDPOINT "tcp://localhost:5555"

int main()

{

zsock_t *client = zsock_new_req(SERVER_ENDPOINT);

printf("I: Connecting to server...\n");

assert(client);

int sequence = 0;

int retries_left = REQUEST_RETRIES;

printf("Entering while loop...\n");

while(retries_left) // interrupt needs to be handled

{

// We send a request, then we get a reply

char request[10];

sprintf(request, "%d", ++sequence);

zstr_send(client, request);

int expect_reply = 1;

while(expect_reply)

{

printf("Expecting reply....\n");

zmq_pollitem_t items [] = {{zsock_resolve(client), 0, ZMQ_POLLIN, 0}};

printf("After polling\n");

int rc = zmq_poll(items, 1, REQUEST_TIMEOUT * ZMQ_POLL_MSEC);

printf("Polling Done.. \n");

if (rc == -1)

break; // Interrupted

// Here we process a server reply and exit our loop if the

// reply is valid. If we didn't get a reply we close the

// client socket, open it again and resend the request. We

// try a number times before finally abandoning:

if (items[0].revents & ZMQ_POLLIN)

{

// We got a reply from the server, must match sequence

char *reply = zstr_recv(client);

if(!reply)

break; // interrupted

if (atoi(reply) == sequence)

{

printf("I: server replied OK (%s)\n", reply);

retries_left=REQUEST_RETRIES;

expect_reply = 0;

}

else

{

printf("E: malformed reply from server: %s\n", reply);

}

free(reply);

}

else

{

if(--retries_left == 0)

{

printf("E: Server seems to be offline, abandoning\n");

break;

}

else

{

printf("W: no response from server, retrying...\n");

zsock_destroy(&client);

printf("I: reconnecting to server...\n");

client = zsock_new_req(SERVER_ENDPOINT);

zstr_send(client, request);

}

}

}

zsock_destroy(&client);

return 0;

}

}lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in C++

//

// Lazy Pirate client

// Use zmq_poll to do a safe request-reply

// To run, start piserver and then randomly kill/restart it

//

#include "zhelpers.hpp"

#include <sstream>

#define REQUEST_TIMEOUT 2500 // msecs, (> 1000!)

#define REQUEST_RETRIES 3 // Before we abandon

// Helper function that returns a new configured socket

// connected to the Hello World server

//

static zmq::socket_t * s_client_socket (zmq::context_t & context) {

std::cout << "I: connecting to server..." << std::endl;

zmq::socket_t * client = new zmq::socket_t (context, ZMQ_REQ);

client->connect ("tcp://localhost:5555");

// Configure socket to not wait at close time

int linger = 0;

client->setsockopt (ZMQ_LINGER, &linger, sizeof (linger));

return client;

}

int main () {

zmq::context_t context (1);

zmq::socket_t * client = s_client_socket (context);

int sequence = 0;

int retries_left = REQUEST_RETRIES;

while (retries_left) {

std::stringstream request;

request << ++sequence;

s_send (*client, request.str());

sleep (1);

bool expect_reply = true;

while (expect_reply) {

// Poll socket for a reply, with timeout

zmq::pollitem_t items[] = {

{ *client, 0, ZMQ_POLLIN, 0 } };

zmq::poll (&items[0], 1, REQUEST_TIMEOUT);

// If we got a reply, process it

if (items[0].revents & ZMQ_POLLIN) {

// We got a reply from the server, must match sequence

std::string reply = s_recv (*client);

if (atoi (reply.c_str ()) == sequence) {

std::cout << "I: server replied OK (" << reply << ")" << std::endl;

retries_left = REQUEST_RETRIES;

expect_reply = false;

}

else {

std::cout << "E: malformed reply from server: " << reply << std::endl;

}

}

else

if (--retries_left == 0) {

std::cout << "E: server seems to be offline, abandoning" << std::endl;

expect_reply = false;

break;

}

else {

std::cout << "W: no response from server, retrying..." << std::endl;

// Old socket will be confused; close it and open a new one

delete client;

client = s_client_socket (context);

// Send request again, on new socket

s_send (*client, request.str());

}

}

}

delete client;

return 0;

}

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in C#

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using System.Text;

using System.Threading;

using ZeroMQ;

namespace Examples

{

static partial class Program

{

//

// Lazy Pirate client

// Use zmq_poll (pollItem.PollIn) to do a safe request-reply

// To run, start lpserver and then randomly kill/restart it

//

// Author: metadings

//

static TimeSpan LPClient_RequestTimeout = TimeSpan.FromMilliseconds(2000);

static int LPClient_RequestRetries = 3;

static ZSocket LPClient_CreateZSocket(ZContext context, string name, out ZError error)

{

// Helper function that returns a new configured socket

// connected to the Lazy Pirate queue

var requester = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.REQ);

requester.IdentityString = name;

requester.Linger = TimeSpan.FromMilliseconds(1);

if (!requester.Connect("tcp://127.0.0.1:5555", out error))

{

return null;

}

return requester;

}

public static void LPClient(string[] args)

{

if (args == null || args.Length < 1)

{

Console.WriteLine();

Console.WriteLine("Usage: ./{0} LPClient [Name]", AppDomain.CurrentDomain.FriendlyName);

Console.WriteLine();

Console.WriteLine(" Name Your name. Default: People");

Console.WriteLine();

args = new string[] { "People" };

}

string name = args[0];

using (var context = new ZContext())

{

ZSocket requester = null;

try

{ // using (requester)

ZError error;

if (null == (requester = LPClient_CreateZSocket(context, name, out error)))

{

if (error == ZError.ETERM)

return; // Interrupted

throw new ZException(error);

}

int sequence = 0;

int retries_left = LPClient_RequestRetries;

var poll = ZPollItem.CreateReceiver();

while (retries_left > 0)

{

// We send a request, then we work to get a reply

using (var outgoing = ZFrame.Create(4))

{

outgoing.Write(++sequence);

if (!requester.Send(outgoing, out error))

{

if (error == ZError.ETERM)

return; // Interrupted

throw new ZException(error);

}

}

ZMessage incoming;

while (true)

{

// Here we process a server reply and exit our loop

// if the reply is valid.

// If we didn't a reply, we close the client socket

// and resend the request. We try a number of times

// before finally abandoning:

// Poll socket for a reply, with timeout

if (requester.PollIn(poll, out incoming, out error, LPClient_RequestTimeout))

{

using (incoming)

{

// We got a reply from the server

int incoming_sequence = incoming[0].ReadInt32();

if (sequence == incoming_sequence)

{

Console.WriteLine("I: server replied OK ({0})", incoming_sequence);

retries_left = LPClient_RequestRetries;

break;

}

else

{

Console_WriteZMessage("E: malformed reply from server", incoming);

}

}

}

else

{

if (error == ZError.EAGAIN)

{

if (--retries_left == 0)

{

Console.WriteLine("E: server seems to be offline, abandoning");

break;

}

Console.WriteLine("W: no response from server, retrying...");

// Old socket is confused; close it and open a new one

requester.Dispose();

if (null == (requester = LPClient_CreateZSocket(context, name, out error)))

{

if (error == ZError.ETERM)

return; // Interrupted

throw new ZException(error);

}

Console.WriteLine("I: reconnected");

// Send request again, on new socket

using (var outgoing = ZFrame.Create(4))

{

outgoing.Write(sequence);

if (!requester.Send(outgoing, out error))

{

if (error == ZError.ETERM)

return; // Interrupted

throw new ZException(error);

}

}

continue;

}

if (error == ZError.ETERM)

return; // Interrupted

throw new ZException(error);

}

}

}

}

finally

{

if (requester != null)

{

requester.Dispose();

requester = null;

}

}

}

}

}

}

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in CL

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Delphi

program lpclient;

//

// Lazy Pirate client

// Use zmq_poll to do a safe request-reply

// To run, start lpserver and then randomly kill/restart it

// @author Varga Balazs <bb.varga@gmail.com>

//

{$APPTYPE CONSOLE}

uses

SysUtils

, zmqapi

;

const

REQUEST_TIMEOUT = 2500; // msecs, (> 1000!)

REQUEST_RETRIES = 3; // Before we abandon

SERVER_ENDPOINT = 'tcp://localhost:5555';

var

ctx: TZMQContext;

client: TZMQSocket;

sequence,

retries_left,

expect_reply: Integer;

request,

reply: Utf8String;

poller: TZMQPoller;

begin

ctx := TZMQContext.create;

Writeln( 'I: connecting to server...' );

client := ctx.Socket( stReq );

client.Linger := 0;

client.connect( SERVER_ENDPOINT );

poller := TZMQPoller.Create( true );

poller.Register( client, [pePollIn] );

sequence := 0;

retries_left := REQUEST_RETRIES;

while ( retries_left > 0 ) and not ctx.Terminated do

try

// We send a request, then we work to get a reply

inc( sequence );

request := Format( '%d', [sequence] );

client.send( request );

expect_reply := 1;

while ( expect_reply > 0 ) do

begin

// Poll socket for a reply, with timeout

poller.poll( REQUEST_TIMEOUT );

// Here we process a server reply and exit our loop if the

// reply is valid. If we didn't a reply we close the client

// socket and resend the request. We try a number of times

// before finally abandoning:

if pePollIn in poller.PollItem[0].revents then

begin

// We got a reply from the server, must match sequence

client.recv( reply );

if StrToInt( reply ) = sequence then

begin

Writeln( Format( 'I: server replied OK (%s)', [reply] ) );

retries_left := REQUEST_RETRIES;

expect_reply := 0;

end else

Writeln( Format( 'E: malformed reply from server: %s', [ reply ] ) );

end else

begin

dec( retries_left );

if retries_left = 0 then

begin

Writeln( 'E: server seems to be offline, abandoning' );

break;

end else

begin

Writeln( 'W: no response from server, retrying...' );

// Old socket is confused; close it and open a new one

poller.Deregister( client, [pePollIn] );

client.Free;

Writeln( 'I: reconnecting to server...' );

client := ctx.Socket( stReq );

client.Linger := 0;

client.connect( SERVER_ENDPOINT );

poller.Register( client, [pePollIn] );

// Send request again, on new socket

client.send( request );

end;

end;

end;

except

end;

poller.Free;

ctx.Free;

end.

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Erlang

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Elixir

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in F#

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Felix

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Go

// Lazy Pirate client

// Use zmq_poll to do a safe request-reply

// To run, start lpserver and then randomly kill/restart it

//

// Author: iano <scaly.iano@gmail.com>

// Based on C example

package main

import (

"fmt"

zmq "github.com/alecthomas/gozmq"

"strconv"

"time"

)

const (

REQUEST_TIMEOUT = time.Duration(2500) * time.Millisecond

REQUEST_RETRIES = 3

SERVER_ENDPOINT = "tcp://localhost:5555"

)

func main() {

context, _ := zmq.NewContext()

defer context.Close()

fmt.Println("I: Connecting to server...")

client, _ := context.NewSocket(zmq.REQ)

client.Connect(SERVER_ENDPOINT)

for sequence, retriesLeft := 1, REQUEST_RETRIES; retriesLeft > 0; sequence++ {

fmt.Printf("I: Sending (%d)\n", sequence)

client.Send([]byte(strconv.Itoa(sequence)), 0)

for expectReply := true; expectReply; {

// Poll socket for a reply, with timeout

items := zmq.PollItems{

zmq.PollItem{Socket: client, Events: zmq.POLLIN},

}

if _, err := zmq.Poll(items, REQUEST_TIMEOUT); err != nil {

panic(err) // Interrupted

}

// .split process server reply

// Here we process a server reply and exit our loop if the

// reply is valid. If we didn't a reply we close the client

// socket and resend the request. We try a number of times

// before finally abandoning:

if item := items[0]; item.REvents&zmq.POLLIN != 0 {

// We got a reply from the server, must match sequence

reply, err := item.Socket.Recv(0)

if err != nil {

panic(err) // Interrupted

}

if replyInt, err := strconv.Atoi(string(reply)); replyInt == sequence && err == nil {

fmt.Printf("I: Server replied OK (%s)\n", reply)

retriesLeft = REQUEST_RETRIES

expectReply = false

} else {

fmt.Printf("E: Malformed reply from server: %s", reply)

}

} else if retriesLeft--; retriesLeft == 0 {

fmt.Println("E: Server seems to be offline, abandoning")

client.SetLinger(0)

client.Close()

break

} else {

fmt.Println("W: No response from server, retrying...")

// Old socket is confused; close it and open a new one

client.SetLinger(0)

client.Close()

client, _ = context.NewSocket(zmq.REQ)

client.Connect(SERVER_ENDPOINT)

fmt.Printf("I: Resending (%d)\n", sequence)

// Send request again, on new socket

client.Send([]byte(strconv.Itoa(sequence)), 0)

}

}

}

}

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Haskell

{--

Lazy Pirate client in Haskell

--}

module Main where

import System.ZMQ4.Monadic

import System.Random (randomRIO)

import System.Exit (exitSuccess)

import Control.Monad (forever, when)

import Control.Concurrent (threadDelay)

import Data.ByteString.Char8 (pack, unpack)

requestRetries = 3

requestTimeout_ms = 2500

serverEndpoint = "tcp://localhost:5555"

main :: IO ()

main =

runZMQ $ do

liftIO $ putStrLn "I: Connecting to server"

client <- socket Req

connect client serverEndpoint

sendServer 1 requestRetries client

sendServer :: Int -> Int -> Socket z Req -> ZMQ z ()

sendServer _ 0 _ = return ()

sendServer seq retries client = do

send client [] (pack $ show seq)

pollServer seq retries client

pollServer :: Int -> Int -> Socket z Req -> ZMQ z ()

pollServer seq retries client = do

[evts] <- poll requestTimeout_ms [Sock client [In] Nothing]

if In `elem` evts

then do

reply <- receive client

if (read . unpack $ reply) == seq

then do

liftIO $ putStrLn $ "I: Server replied OK " ++ (unpack reply)

sendServer (seq+1) requestRetries client

else do

liftIO $ putStrLn $ "E: malformed reply from server: " ++ (unpack reply)

pollServer seq retries client

else

if retries == 0

then liftIO $ putStrLn "E: Server seems to be offline, abandoning" >> exitSuccess

else do

liftIO $ putStrLn $ "W: No response from server, retrying..."

client' <- socket Req

connect client' serverEndpoint

send client' [] (pack $ show seq)

pollServer seq (retries-1) client'

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Haxe

package ;

import haxe.Stack;

import neko.Lib;

import org.zeromq.ZContext;

import org.zeromq.ZFrame;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ;

import org.zeromq.ZMQException;

import org.zeromq.ZMQPoller;

import org.zeromq.ZSocket;

/**

* Lazy Pirate client

* Use zmq_poll to do a safe request-reply

* To run, start lpserver and then randomly kill / restart it.

*

* @see http://zguide.zeromq.org/page:all#Client-side-Reliability-Lazy-Pirate-Pattern

*/

class LPClient

{

private static inline var REQUEST_TIMEOUT = 2500; // msecs, (> 1000!)

private static inline var REQUEST_RETRIES = 3; // Before we abandon

private static inline var SERVER_ENDPOINT = "tcp://localhost:5555";

public static function main() {

Lib.println("** LPClient (see: http://zguide.zeromq.org/page:all#Client-side-Reliability-Lazy-Pirate-Pattern)");

var ctx:ZContext = new ZContext();

Lib.println("I: connecting to server ...");

var client = ctx.createSocket(ZMQ_REQ);

if (client == null)

return;

client.connect(SERVER_ENDPOINT);

var sequence = 0;

var retries_left = REQUEST_RETRIES;

var poller = new ZMQPoller();

while (retries_left > 0 && !ZMQ.isInterrupted()) {

// We send a request, then we work to get a reply

var request = Std.string(++sequence);

ZFrame.newStringFrame(request).send(client);

var expect_reply = true;

while (expect_reply) {

poller.registerSocket(client, ZMQ.ZMQ_POLLIN());

// Poll socket for a reply, with timeout

try {

var res = poller.poll(REQUEST_TIMEOUT * 1000);

} catch (e:ZMQException) {

trace("ZMQException #:" + e.errNo + ", str:" + e.str());

trace (Stack.toString(Stack.exceptionStack()));

ctx.destroy();

return;

}

// If we got a reply, process it

if (poller.pollin(1)) {

// We got a reply from the server, must match sequence

var replyFrame = ZFrame.recvFrame(client);

if (replyFrame == null)

break; // Interrupted

if (Std.parseInt(replyFrame.toString()) == sequence) {

Lib.println("I: server replied OK (" + sequence + ")");

retries_left = REQUEST_RETRIES;

expect_reply = false;

} else

Lib.println("E: malformed reply from server: " + replyFrame.toString());

replyFrame.destroy();

} else if (--retries_left == 0) {

Lib.println("E: server seems to be offline, abandoning");

break;

} else {

Lib.println("W: no response from server, retrying...");

// Old socket is confused, close it and open a new one

ctx.destroySocket(client);

Lib.println("I: reconnecting to server...");

client = ctx.createSocket(ZMQ_REQ);

client.connect(SERVER_ENDPOINT);

// Send request again, on new socket

ZFrame.newStringFrame(request).send(client);

}

poller.unregisterAllSockets();

}

}

ctx.destroy();

}

}lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Java

package guide;

import org.zeromq.SocketType;

import org.zeromq.ZContext;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ.Poller;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ.Socket;

//

// Lazy Pirate client

// Use zmq_poll to do a safe request-reply

// To run, start lpserver and then randomly kill/restart it

//

public class lpclient

{

private final static int REQUEST_TIMEOUT = 2500; // msecs, (> 1000!)

private final static int REQUEST_RETRIES = 3; // Before we abandon

private final static String SERVER_ENDPOINT = "tcp://localhost:5555";

public static void main(String[] argv)

{

try (ZContext ctx = new ZContext()) {

System.out.println("I: connecting to server");

Socket client = ctx.createSocket(SocketType.REQ);

assert (client != null);

client.connect(SERVER_ENDPOINT);

Poller poller = ctx.createPoller(1);

poller.register(client, Poller.POLLIN);

int sequence = 0;

int retriesLeft = REQUEST_RETRIES;

while (retriesLeft > 0 && !Thread.currentThread().isInterrupted()) {

// We send a request, then we work to get a reply

String request = String.format("%d", ++sequence);

client.send(request);

int expect_reply = 1;

while (expect_reply > 0) {

// Poll socket for a reply, with timeout

int rc = poller.poll(REQUEST_TIMEOUT);

if (rc == -1)

break; // Interrupted

// Here we process a server reply and exit our loop if the

// reply is valid. If we didn't a reply we close the client

// socket and resend the request. We try a number of times

// before finally abandoning:

if (poller.pollin(0)) {

// We got a reply from the server, must match

// getSequence

String reply = client.recvStr();

if (reply == null)

break; // Interrupted

if (Integer.parseInt(reply) == sequence) {

System.out.printf(

"I: server replied OK (%s)\n", reply

);

retriesLeft = REQUEST_RETRIES;

expect_reply = 0;

}

else System.out.printf(

"E: malformed reply from server: %s\n", reply

);

}

else if (--retriesLeft == 0) {

System.out.println(

"E: server seems to be offline, abandoning\n"

);

break;

}

else {

System.out.println(

"W: no response from server, retrying\n"

);

// Old socket is confused; close it and open a new one

poller.unregister(client);

ctx.destroySocket(client);

System.out.println("I: reconnecting to server\n");

client = ctx.createSocket(SocketType.REQ);

client.connect(SERVER_ENDPOINT);

poller.register(client, Poller.POLLIN);

// Send request again, on new socket

client.send(request);

}

}

}

}

}

}

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Julia

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Lua

--

-- Lazy Pirate client

-- Use zmq_poll to do a safe request-reply

-- To run, start lpserver and then randomly kill/restart it

--

-- Author: Robert G. Jakabosky <bobby@sharedrealm.com>

--

require"zmq"

require"zmq.poller"

require"zhelpers"

local REQUEST_TIMEOUT = 2500 -- msecs, (> 1000!)

local REQUEST_RETRIES = 3 -- Before we abandon

-- Helper function that returns a new configured socket

-- connected to the Hello World server

--

local function s_client_socket(context)

printf ("I: connecting to server...\n")

local client = context:socket(zmq.REQ)

client:connect("tcp://localhost:5555")

-- Configure socket to not wait at close time

client:setopt(zmq.LINGER, 0)

return client

end

s_version_assert (2, 1)

local context = zmq.init(1)

local client = s_client_socket (context)

local sequence = 0

local retries_left = REQUEST_RETRIES

local expect_reply = true

local poller = zmq.poller(1)

local function client_cb()

-- We got a reply from the server, must match sequence

--local reply = assert(client:recv(zmq.NOBLOCK))

local reply = client:recv()

if (tonumber(reply) == sequence) then

printf ("I: server replied OK (%s)\n", reply)

retries_left = REQUEST_RETRIES

expect_reply = false

else

printf ("E: malformed reply from server: %s\n", reply)

end

end

poller:add(client, zmq.POLLIN, client_cb)

while (retries_left > 0) do

sequence = sequence + 1

-- We send a request, then we work to get a reply

local request = string.format("%d", sequence)

client:send(request)

expect_reply = true

while (expect_reply) do

-- Poll socket for a reply, with timeout

local cnt = assert(poller:poll(REQUEST_TIMEOUT * 1000))

-- Check if there was no reply

if (cnt == 0) then

retries_left = retries_left - 1

if (retries_left == 0) then

printf ("E: server seems to be offline, abandoning\n")

break

else

printf ("W: no response from server, retrying...\n")

-- Old socket is confused; close it and open a new one

poller:remove(client)

client:close()

client = s_client_socket (context)

poller:add(client, zmq.POLLIN, client_cb)

-- Send request again, on new socket

client:send(request)

end

end

end

end

client:close()

context:term()

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Node.js

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Objective-C

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in ooc

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Perl

# Lazy Pirate client in Perl

# Use poll to do a safe request-reply

# To run, start lpserver.pl then randomly kill/restart it

use strict;

use warnings;

use v5.10;

use ZMQ::FFI;

use ZMQ::FFI::Constants qw(ZMQ_REQ);

use EV;

my $REQUEST_TIMEOUT = 2500; # msecs

my $REQUEST_RETRIES = 3; # Before we abandon

my $SERVER_ENDPOINT = 'tcp://localhost:5555';

my $ctx = ZMQ::FFI->new();

say 'I: connecting to server...';

my $client = $ctx->socket(ZMQ_REQ);

$client->connect($SERVER_ENDPOINT);

my $sequence = 0;

my $retries_left = $REQUEST_RETRIES;

REQUEST_LOOP:

while ($retries_left) {

# We send a request, then we work to get a reply

my $request = ++$sequence;

$client->send($request);

my $expect_reply = 1;

RETRY_LOOP:

while ($expect_reply) {

# Poll socket for a reply, with timeout

EV::once $client->get_fd, EV::READ, $REQUEST_TIMEOUT / 1000, sub {

my ($revents) = @_;

# Here we process a server reply and exit our loop if the

# reply is valid. If we didn't get a reply we close the client

# socket and resend the request. We try a number of times

# before finally abandoning:

if ($revents == EV::READ) {

while ($client->has_pollin) {

# We got a reply from the server, must match sequence

my $reply = $client->recv();

if ($reply == $sequence) {

say "I: server replied OK ($reply)";

$retries_left = $REQUEST_RETRIES;

$expect_reply = 0;

}

else {

say "E: malformed reply from server: $reply";

}

}

}

elsif (--$retries_left == 0) {

say 'E: server seems to be offline, abandoning';

}

else {

say "W: no response from server, retrying...";

# Old socket is confused; close it and open a new one

$client->close;

say "reconnecting to server...";

$client = $ctx->socket(ZMQ_REQ);

$client->connect($SERVER_ENDPOINT);

# Send request again, on new socket

$client->send($request);

}

};

last RETRY_LOOP if $retries_left == 0;

EV::run;

}

}

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in PHP

<?php

/*

* Lazy Pirate client

* Use zmq_poll to do a safe request-reply

* To run, start lpserver and then randomly kill/restart it

*

* @author Ian Barber <ian(dot)barber(at)gmail(dot)com>

*/

define("REQUEST_TIMEOUT", 2500); // msecs, (> 1000!)

define("REQUEST_RETRIES", 3); // Before we abandon

/*

* Helper function that returns a new configured socket

* connected to the Hello World server

*/

function client_socket(ZMQContext $context)

{

echo "I: connecting to server...", PHP_EOL;

$client = new ZMQSocket($context,ZMQ::SOCKET_REQ);

$client->connect("tcp://localhost:5555");

// Configure socket to not wait at close time

$client->setSockOpt(ZMQ::SOCKOPT_LINGER, 0);

return $client;

}

$context = new ZMQContext();

$client = client_socket($context);

$sequence = 0;

$retries_left = REQUEST_RETRIES;

$read = $write = array();

while ($retries_left) {

// We send a request, then we work to get a reply

$client->send(++$sequence);

$expect_reply = true;

while ($expect_reply) {

// Poll socket for a reply, with timeout

$poll = new ZMQPoll();

$poll->add($client, ZMQ::POLL_IN);

$events = $poll->poll($read, $write, REQUEST_TIMEOUT);

// If we got a reply, process it

if ($events > 0) {

// We got a reply from the server, must match sequence

$reply = $client->recv();

if (intval($reply) == $sequence) {

printf ("I: server replied OK (%s)%s", $reply, PHP_EOL);

$retries_left = REQUEST_RETRIES;

$expect_reply = false;

} else {

printf ("E: malformed reply from server: %s%s", $reply, PHP_EOL);

}

} elseif (--$retries_left == 0) {

echo "E: server seems to be offline, abandoning", PHP_EOL;

break;

} else {

echo "W: no response from server, retrying...", PHP_EOL;

// Old socket will be confused; close it and open a new one

$client = client_socket($context);

// Send request again, on new socket

$client->send($sequence);

}

}

}

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Python

#

# Lazy Pirate client

# Use zmq_poll to do a safe request-reply

# To run, start lpserver and then randomly kill/restart it

#

# Author: Daniel Lundin <dln(at)eintr(dot)org>

#

import itertools

import logging

import sys

import zmq

logging.basicConfig(format="%(levelname)s: %(message)s", level=logging.INFO)

REQUEST_TIMEOUT = 2500

REQUEST_RETRIES = 3

SERVER_ENDPOINT = "tcp://localhost:5555"

context = zmq.Context()

logging.info("Connecting to server…")

client = context.socket(zmq.REQ)

client.connect(SERVER_ENDPOINT)

for sequence in itertools.count():

request = str(sequence).encode()

logging.info("Sending (%s)", request)

client.send(request)

retries_left = REQUEST_RETRIES

while True:

if (client.poll(REQUEST_TIMEOUT) & zmq.POLLIN) != 0:

reply = client.recv()

if int(reply) == sequence:

logging.info("Server replied OK (%s)", reply)

retries_left = REQUEST_RETRIES

break

else:

logging.error("Malformed reply from server: %s", reply)

continue

retries_left -= 1

logging.warning("No response from server")

# Socket is confused. Close and remove it.

client.setsockopt(zmq.LINGER, 0)

client.close()

if retries_left == 0:

logging.error("Server seems to be offline, abandoning")

sys.exit()

logging.info("Reconnecting to server…")

# Create new connection

client = context.socket(zmq.REQ)

client.connect(SERVER_ENDPOINT)

logging.info("Resending (%s)", request)

client.send(request)

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Q

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Racket

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Ruby

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Rust

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Scala

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in Tcl

lpclient: Lazy Pirate client in OCaml

Run this together with the matching server:

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Ada

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Basic

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in C

// Lazy Pirate server

// Binds REQ socket to tcp://*:5555

// Like hwserver except:

// - echoes request as-is

// - randomly runs slowly, or exits to simulate a crash.

#include "zhelpers.h"

#include <unistd.h>

int main (void)

{

srandom ((unsigned) time (NULL));

void *context = zmq_ctx_new ();

void *server = zmq_socket (context, ZMQ_REP);

zmq_bind (server, "tcp://*:5555");

int cycles = 0;

while (1) {

char *request = s_recv (server);

cycles++;

// Simulate various problems, after a few cycles

if (cycles > 3 && randof (3) == 0) {

printf ("I: simulating a crash\n");

break;

}

else

if (cycles > 3 && randof (3) == 0) {

printf ("I: simulating CPU overload\n");

sleep (2);

}

printf ("I: normal request (%s)\n", request);

sleep (1); // Do some heavy work

s_send (server, request);

free (request);

}

zmq_close (server);

zmq_ctx_destroy (context);

return 0;

}

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in C++

//

// Lazy Pirate server

// Binds REQ socket to tcp://*:5555

// Like hwserver except:

// - echoes request as-is

// - randomly runs slowly, or exits to simulate a crash.

//

#include "zhelpers.hpp"

int main ()

{

srandom ((unsigned) time (NULL));

zmq::context_t context(1);

zmq::socket_t server(context, ZMQ_REP);

server.bind("tcp://*:5555");

int cycles = 0;

while (1) {

std::string request = s_recv (server);

cycles++;

// Simulate various problems, after a few cycles

if (cycles > 3 && within (3) == 0) {

std::cout << "I: simulating a crash" << std::endl;

break;

}

else

if (cycles > 3 && within (3) == 0) {

std::cout << "I: simulating CPU overload" << std::endl;

sleep (2);

}

std::cout << "I: normal request (" << request << ")" << std::endl;

sleep (1); // Do some heavy work

s_send (server, request);

}

return 0;

}

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in C#

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using System.Text;

using System.Threading;

using ZeroMQ;

namespace Examples

{

static partial class Program

{

//

// Lazy Pirate server

// Binds REP socket to tcp://*:5555

// Like hwserver except:

// - echoes request as-is

// - randomly runs slowly, or exits to simulate a crash.

//

// Author: metadings

//

public static void LPServer(string[] args)

{

using (var context = new ZContext())

using (var responder = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.REP))

{

responder.Bind("tcp://*:5555");

ZError error;

int cycles = 0;

var rnd = new Random();

while (true)

{

ZMessage incoming;

if (null == (incoming = responder.ReceiveMessage(out error)))

{

if (error == ZError.ETERM)

return; // Interrupted

throw new ZException(error);

}

using (incoming)

{

++cycles;

// Simulate various problems, after a few cycles

if (cycles > 16 && rnd.Next(16) == 0)

{

Console.WriteLine("I: simulating a crash");

break;

}

else if (cycles > 4 && rnd.Next(4) == 0)

{

Console.WriteLine("I: simulating CPU overload");

Thread.Sleep(1000);

}

Console.WriteLine("I: normal request ({0})", incoming[0].ReadInt32());

Thread.Sleep(1); // Do some heavy work

responder.Send(incoming);

}

}

}

}

}

}

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in CL

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Delphi

program lpserver;

//

// Lazy Pirate server

// Binds REQ socket to tcp://*:5555

// Like hwserver except:

// - echoes request as-is

// - randomly runs slowly, or exits to simulate a crash.

// @author Varga Balazs <bb.varga@gmail.com>

//

{$APPTYPE CONSOLE}

uses

SysUtils

, zmqapi

;

var

context: TZMQContext;

server: TZMQSocket;

cycles: Integer;

request: Utf8String;

begin

Randomize;

context := TZMQContext.create;

server := context.socket( stRep );

server.bind( 'tcp://*:5555' );

cycles := 0;

while not context.Terminated do

try

server.recv( request );

inc( cycles );

// Simulate various problems, after a few cycles

if ( cycles > 3 ) and ( random(3) = 0) then

begin

Writeln( 'I: simulating a crash' );

break;

end else

if ( cycles > 3 ) and ( random(3) = 0 ) then

begin

Writeln( 'I: simulating CPU overload' );

sleep(2000);

end;

Writeln( Format( 'I: normal request (%s)', [request] ) );

sleep (1000); // Do some heavy work

server.send( request );

except

end;

context.Free;

end.

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Erlang

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Elixir

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in F#

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Felix

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Go

// Lazy Pirate server

// Binds REQ socket to tcp://*:5555

// Like hwserver except:

// - echoes request as-is

// - randomly runs slowly, or exits to simulate a crash.

//

// Author: iano <scaly.iano@gmail.com>

// Based on C example

package main

import (

"fmt"

zmq "github.com/alecthomas/gozmq"

"math/rand"

"time"

)

const (

SERVER_ENDPOINT = "tcp://*:5555"

)

func main() {

src := rand.NewSource(time.Now().UnixNano())

random := rand.New(src)

context, _ := zmq.NewContext()

defer context.Close()

server, _ := context.NewSocket(zmq.REP)

defer server.Close()

server.Bind(SERVER_ENDPOINT)

for cycles := 1; ; cycles++ {

request, _ := server.Recv(0)

// Simulate various problems, after a few cycles

if cycles > 3 {

switch r := random.Intn(3); r {

case 0:

fmt.Println("I: Simulating a crash")

return

case 1:

fmt.Println("I: simulating CPU overload")

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

}

}

fmt.Printf("I: normal request (%s)\n", request)

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second) // Do some heavy work

server.Send(request, 0)

}

}

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Haskell

{--

Lazy Pirate server in Haskell

--}

module Main where

import System.ZMQ4.Monadic

import System.Random (randomRIO)

import System.Exit (exitSuccess)

import Control.Monad (forever, when)

import Control.Concurrent (threadDelay)

import Data.ByteString.Char8 (pack, unpack)

main :: IO ()

main =

runZMQ $ do

server <- socket Rep

bind server "tcp://*:5555"

sendClient 0 server

sendClient :: Int -> Socket z Rep -> ZMQ z ()

sendClient cycles server = do

req <- receive server

chance <- liftIO $ randomRIO (0::Int, 3)

when (cycles > 3 && chance == 0) $ do

liftIO crash

chance' <- liftIO $ randomRIO (0::Int, 3)

when (cycles > 3 && chance' == 0) $ do

liftIO overload

liftIO $ putStrLn $ "I: normal request " ++ (unpack req)

liftIO $ threadDelay $ 1 * 1000 * 1000

send server [] req

sendClient (cycles+1) server

crash = do

putStrLn "I: Simulating a crash"

exitSuccess

overload = do

putStrLn "I: Simulating CPU overload"

threadDelay $ 2 * 1000 * 1000

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Haxe

package ;

import neko.Lib;

import neko.Sys;

import org.zeromq.ZContext;

import org.zeromq.ZFrame;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ;

/**

* Lazy Pirate server

* Binds REP socket to tcp://*:5555

* Like HWServer except:

* - echoes request as-is

* - randomly runs slowly, or exists to simulate a crash.

*

* @see http://zguide.zeromq.org/page:all#Client-side-Reliability-Lazy-Pirate-Pattern

*

*/

class LPServer

{

public static function main() {

Lib.println("** LPServer (see: http://zguide.zeromq.org/page:all#Client-side-Reliability-Lazy-Pirate-Pattern)");

var ctx = new ZContext();

var server = ctx.createSocket(ZMQ_REP);

server.bind("tcp://*:5555");

var cycles = 0;

while (true) {

var requestFrame = ZFrame.recvFrame(server);

cycles++;

// Simulate various problems, after a few cycles

if (cycles > 3 && ZHelpers.randof(3) == 0) {

Lib.println("I: simulating a crash");

break;

}

else if (cycles > 3 && ZHelpers.randof(3) == 0) {

Lib.println("I: simulating CPU overload");

Sys.sleep(2.0);

}

Lib.println("I: normal request (" + requestFrame.toString() + ")");

Sys.sleep(1.0); // Do some heavy work

requestFrame.send(server);

requestFrame.destroy();

}

server.close();

ctx.destroy();

}

}lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Java

package guide;

import java.util.Random;

import org.zeromq.SocketType;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ.Socket;

import org.zeromq.ZContext;

//

// Lazy Pirate server

// Binds REQ socket to tcp://*:5555

// Like hwserver except:

// - echoes request as-is

// - randomly runs slowly, or exits to simulate a crash.

//

public class lpserver

{

public static void main(String[] argv) throws Exception

{

Random rand = new Random(System.nanoTime());

try (ZContext context = new ZContext()) {

Socket server = context.createSocket(SocketType.REP);

server.bind("tcp://*:5555");

int cycles = 0;

while (true) {

String request = server.recvStr();

cycles++;

// Simulate various problems, after a few cycles

if (cycles > 3 && rand.nextInt(3) == 0) {

System.out.println("I: simulating a crash");

break;

}

else if (cycles > 3 && rand.nextInt(3) == 0) {

System.out.println("I: simulating CPU overload");

Thread.sleep(2000);

}

System.out.printf("I: normal request (%s)\n", request);

Thread.sleep(1000); // Do some heavy work

server.send(request);

}

}

}

}

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Julia

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Lua

--

-- Lazy Pirate server

-- Binds REQ socket to tcp://*:5555

-- Like hwserver except:

-- - echoes request as-is

-- - randomly runs slowly, or exits to simulate a crash.

--

-- Author: Robert G. Jakabosky <bobby@sharedrealm.com>

--

require"zmq"

require"zhelpers"

math.randomseed(os.time())

local context = zmq.init(1)

local server = context:socket(zmq.REP)

server:bind("tcp://*:5555")

local cycles = 0

while true do

local request = server:recv()

cycles = cycles + 1

-- Simulate various problems, after a few cycles

if (cycles > 3 and randof (3) == 0) then

printf("I: simulating a crash\n")

break

elseif (cycles > 3 and randof (3) == 0) then

printf("I: simulating CPU overload\n")

s_sleep(2000)

end

printf("I: normal request (%s)\n", request)

s_sleep(1000) -- Do some heavy work

server:send(request)

end

server:close()

context:term()

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Node.js

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Objective-C

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in ooc

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Perl

# Lazy Pirate server in Perl

# Binds REQ socket to tcp://*:5555

# Like hwserver except:

# - echoes request as-is

# - randomly runs slowly, or exits to simulate a crash.

use strict;

use warnings;

use v5.10;

use ZMQ::FFI;

use ZMQ::FFI::Constants qw(ZMQ_REP);

my $context = ZMQ::FFI->new();

my $server = $context->socket(ZMQ_REP);

$server->bind('tcp://*:5555');

my $cycles = 0;

SERVER_LOOP:

while (1) {

my $request = $server->recv();

$cycles++;

# Simulate various problems, after a few cycles

if ($cycles > 3 && int(rand(3)) == 0) {

say "I: simulating a crash";

last SERVER_LOOP;

}

elsif ($cycles > 3 && int(rand(3)) == 0) {

say "I: simulating CPU overload";

sleep 2;

}

say "I: normal request ($request)";

sleep 1; # Do some heavy work

$server->send($request);

}

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in PHP

<?php

/*

* Lazy Pirate server

* Binds REQ socket to tcp://*:5555

* Like hwserver except:

* - echoes request as-is

* - randomly runs slowly, or exits to simulate a crash.

*

* @author Ian Barber <ian(dot)barber(at)gmail(dot)com>

*/

$context = new ZMQContext();

$server = new ZMQSocket($context, ZMQ::SOCKET_REP);

$server->bind("tcp://*:5555");

$cycles = 0;

while (true) {

$request = $server->recv();

$cycles++;

// Simulate various problems, after a few cycles

if ($cycles > 3 && rand(0, 3) == 0) {

echo "I: simulating a crash", PHP_EOL;

break;

} elseif ($cycles > 3 && rand(0, 3) == 0) {

echo "I: simulating CPU overload", PHP_EOL;

sleep(5);

}

printf ("I: normal request (%s)%s", $request, PHP_EOL);

sleep(1); // Do some heavy work

$server->send($request);

}

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Python

#

# Lazy Pirate server

# Binds REQ socket to tcp://*:5555

# Like hwserver except:

# - echoes request as-is

# - randomly runs slowly, or exits to simulate a crash.

#

# Author: Daniel Lundin <dln(at)eintr(dot)org>

#

from random import randint

import itertools

import logging

import time

import zmq

logging.basicConfig(format="%(levelname)s: %(message)s", level=logging.INFO)

context = zmq.Context()

server = context.socket(zmq.REP)

server.bind("tcp://*:5555")

for cycles in itertools.count():

request = server.recv()

# Simulate various problems, after a few cycles

if cycles > 3 and randint(0, 3) == 0:

logging.info("Simulating a crash")

break

elif cycles > 3 and randint(0, 3) == 0:

logging.info("Simulating CPU overload")

time.sleep(2)

logging.info("Normal request (%s)", request)

time.sleep(1) # Do some heavy work

server.send(request)

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Q

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Racket

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Ruby

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Rust

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Scala

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in Tcl

lpserver: Lazy Pirate server in OCaml

To run this test case, start the client and the server in two console windows. The server will randomly misbehave after a few messages. You can check the client’s response. Here is typical output from the server:

I: normal request (1)

I: normal request (2)

I: normal request (3)

I: simulating CPU overload

I: normal request (4)

I: simulating a crash

And here is the client’s response:

I: connecting to server...

I: server replied OK (1)

I: server replied OK (2)

I: server replied OK (3)

W: no response from server, retrying...

I: connecting to server...

W: no response from server, retrying...

I: connecting to server...

E: server seems to be offline, abandoning

The client sequences each message and checks that replies come back exactly in order: that no requests or replies are lost, and no replies come back more than once, or out of order. Run the test a few times until you’re convinced that this mechanism actually works. You don’t need sequence numbers in a production application; they just help us trust our design.

The client uses a REQ socket, and does the brute force close/reopen because REQ sockets impose that strict send/receive cycle. You might be tempted to use a DEALER instead, but it would not be a good decision. First, it would mean emulating the secret sauce that REQ does with envelopes (if you’ve forgotten what that is, it’s a good sign you don’t want to have to do it). Second, it would mean potentially getting back replies that you didn’t expect.

Handling failures only at the client works when we have a set of clients talking to a single server. It can handle a server crash, but only if recovery means restarting that same server. If there’s a permanent error, such as a dead power supply on the server hardware, this approach won’t work. Because the application code in servers is usually the biggest source of failures in any architecture, depending on a single server is not a great idea.

So, pros and cons:

- Pro: simple to understand and implement.

- Pro: works easily with existing client and server application code.

- Pro: ZeroMQ automatically retries the actual reconnection until it works.

- Con: doesn’t failover to backup or alternate servers.

Basic Reliable Queuing (Simple Pirate Pattern) #

Our second approach extends the Lazy Pirate pattern with a queue proxy that lets us talk, transparently, to multiple servers, which we can more accurately call “workers”. We’ll develop this in stages, starting with a minimal working model, the Simple Pirate pattern.

In all these Pirate patterns, workers are stateless. If the application requires some shared state, such as a shared database, we don’t know about it as we design our messaging framework. Having a queue proxy means workers can come and go without clients knowing anything about it. If one worker dies, another takes over. This is a nice, simple topology with only one real weakness, namely the central queue itself, which can become a problem to manage, and a single point of failure.

The basis for the queue proxy is the load balancing broker from Chapter 3 - Advanced Request-Reply Patterns. What is the very minimum we need to do to handle dead or blocked workers? Turns out, it’s surprisingly little. We already have a retry mechanism in the client. So using the load balancing pattern will work pretty well. This fits with ZeroMQ’s philosophy that we can extend a peer-to-peer pattern like request-reply by plugging naive proxies in the middle.

We don’t need a special client; we’re still using the Lazy Pirate client. Here is the queue, which is identical to the main task of the load balancing broker:

spqueue: Simple Pirate queue in Ada

spqueue: Simple Pirate queue in Basic

spqueue: Simple Pirate queue in C

// Simple Pirate broker

// This is identical to load-balancing pattern, with no reliability

// mechanisms. It depends on the client for recovery. Runs forever.

#include "czmq.h"

#define WORKER_READY "\001" // Signals worker is ready

int main (void)

{

zctx_t *ctx = zctx_new ();

void *frontend = zsocket_new (ctx, ZMQ_ROUTER);

void *backend = zsocket_new (ctx, ZMQ_ROUTER);

zsocket_bind (frontend, "tcp://*:5555"); // For clients

zsocket_bind (backend, "tcp://*:5556"); // For workers

// Queue of available workers

zlist_t *workers = zlist_new ();

// The body of this example is exactly the same as lbbroker2.

// .skip

while (true) {

zmq_pollitem_t items [] = {

{ backend, 0, ZMQ_POLLIN, 0 },

{ frontend, 0, ZMQ_POLLIN, 0 }

};

// Poll frontend only if we have available workers

int rc = zmq_poll (items, zlist_size (workers)? 2: 1, -1);

if (rc == -1)

break; // Interrupted

// Handle worker activity on backend

if (items [0].revents & ZMQ_POLLIN) {

// Use worker identity for load-balancing

zmsg_t *msg = zmsg_recv (backend);

if (!msg)

break; // Interrupted

zframe_t *identity = zmsg_unwrap (msg);

zlist_append (workers, identity);

// Forward message to client if it's not a READY

zframe_t *frame = zmsg_first (msg);

if (memcmp (zframe_data (frame), WORKER_READY, 1) == 0)

zmsg_destroy (&msg);

else

zmsg_send (&msg, frontend);

}

if (items [1].revents & ZMQ_POLLIN) {

// Get client request, route to first available worker

zmsg_t *msg = zmsg_recv (frontend);

if (msg) {

zmsg_wrap (msg, (zframe_t *) zlist_pop (workers));

zmsg_send (&msg, backend);

}

}

}

// When we're done, clean up properly

while (zlist_size (workers)) {

zframe_t *frame = (zframe_t *) zlist_pop (workers);

zframe_destroy (&frame);

}

zlist_destroy (&workers);

zctx_destroy (&ctx);

return 0;

// .until

}

spqueue: Simple Pirate queue in C++

//

// Simple Pirate queue

// This is identical to the LRU pattern, with no reliability mechanisms

// at all. It depends on the client for recovery. Runs forever.

//

// Andreas Hoelzlwimmer <andreas.hoelzlwimmer@fh-hagenberg.at

#include "zmsg.hpp"

#include <queue>

#define MAX_WORKERS 100

int main (void)

{

s_version_assert (2, 1);

// Prepare our context and sockets

zmq::context_t context(1);

zmq::socket_t frontend (context, ZMQ_ROUTER);

zmq::socket_t backend (context, ZMQ_ROUTER);

frontend.bind("tcp://*:5555"); // For clients

backend.bind("tcp://*:5556"); // For workers

// Queue of available workers

std::queue<std::string> worker_queue;

while (1) {

zmq::pollitem_t items [] = {

{ backend, 0, ZMQ_POLLIN, 0 },

{ frontend, 0, ZMQ_POLLIN, 0 }

};

// Poll frontend only if we have available workers

if (worker_queue.size())

zmq::poll (items, 2, -1);

else

zmq::poll (items, 1, -1);

// Handle worker activity on backend

if (items [0].revents & ZMQ_POLLIN) {

zmsg zm(backend);

//zmsg_t *zmsg = zmsg_recv (backend);

// Use worker address for LRU routing

assert (worker_queue.size() < MAX_WORKERS);

worker_queue.push(zm.unwrap());

// Return reply to client if it's not a READY

if (strcmp (zm.address(), "READY") == 0)

zm.clear();

else

zm.send (frontend);

}

if (items [1].revents & ZMQ_POLLIN) {

// Now get next client request, route to next worker

zmsg zm(frontend);

// REQ socket in worker needs an envelope delimiter

zm.wrap(worker_queue.front().c_str(), "");

zm.send(backend);

// Dequeue and drop the next worker address

worker_queue.pop();

}

}

// We never exit the main loop

return 0;

}

spqueue: Simple Pirate queue in C#

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using System.Text;

using System.Threading;

using ZeroMQ;

namespace Examples

{

static partial class Program

{

public static void SPQueue(string[] args)

{

//

// Simple Pirate broker

// This is identical to load-balancing pattern, with no reliability

// mechanisms. It depends on the client for recovery. Runs forever.

//

// Author: metadings

//

using (var context = new ZContext())

using (var frontend = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.ROUTER))

using (var backend = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.ROUTER))

{

frontend.Bind("tcp://*:5555");

backend.Bind("tcp://*:5556");

// Queue of available workers

var worker_queue = new List<string>();

ZError error;

ZMessage incoming;

var poll = ZPollItem.CreateReceiver();

while (true)

{

if (backend.PollIn(poll, out incoming, out error, TimeSpan.FromMilliseconds(64)))

{

using (incoming)

{

// Handle worker activity on backend

// incoming[0] is worker_id

string worker_id = incoming[0].ReadString();

// Queue worker identity for load-balancing

worker_queue.Add(worker_id);

// incoming[1] is empty

// incoming[2] is READY or else client_id

string client_id = incoming[2].ReadString();

if (client_id == "READY")

{

Console.WriteLine("I: ({0}) worker ready", worker_id);

}

else

{

// incoming[3] is empty

// incoming[4] is reply

// string reply = incoming[4].ReadString();

// int reply = incoming[4].ReadInt32();

Console.WriteLine("I: ({0}) work complete", worker_id);

using (var outgoing = new ZMessage())

{

outgoing.Add(new ZFrame(client_id));

outgoing.Add(new ZFrame());

outgoing.Add(incoming[4]);

// Send

frontend.Send(outgoing);

}

}

}

}

else

{

if (error == ZError.ETERM)

return;

if (error != ZError.EAGAIN)

throw new ZException(error);

}

if (worker_queue.Count > 0)

{

// Poll frontend only if we have available workers

if (frontend.PollIn(poll, out incoming, out error, TimeSpan.FromMilliseconds(64)))

{

using (incoming)

{

// Here is how we handle a client request

// Dequeue the next worker identity

string worker_id = worker_queue[0];

worker_queue.RemoveAt(0);

// incoming[0] is client_id

string client_id = incoming[0].ReadString();

// incoming[1] is empty

// incoming[2] is request

// string request = incoming[2].ReadString();

int request = incoming[2].ReadInt32();

Console.WriteLine("I: ({0}) working on ({1}) {2}", worker_id, client_id, request);

using (var outgoing = new ZMessage())

{

outgoing.Add(new ZFrame(worker_id));

outgoing.Add(new ZFrame());

outgoing.Add(new ZFrame(client_id));

outgoing.Add(new ZFrame());

outgoing.Add(incoming[2]);

// Send

backend.Send(outgoing);

}

}

}

else

{

if (error == ZError.ETERM)

return;

if (error != ZError.EAGAIN)

throw new ZException(error);

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

spqueue: Simple Pirate queue in CL

spqueue: Simple Pirate queue in Delphi

program spqueue;

//

// Simple Pirate broker

// This is identical to load-balancing pattern, with no reliability

// mechanisms. It depends on the client for recovery. Runs forever.

// @author Varga Balazs <bb.varga@gmail.com>

//

{$APPTYPE CONSOLE}

uses

SysUtils

, zmqapi

;

const

WORKER_READY = '\001'; // Signals worker is ready

var

ctx: TZMQContext;

frontend,

backend: TZMQSocket;

workers: TZMQMsg;

poller: TZMQPoller;

pc: Integer;

msg: TZMQMsg;

identity,

frame: TZMQFrame;

begin

ctx := TZMQContext.create;

frontend := ctx.Socket( stRouter );

backend := ctx.Socket( stRouter );

frontend.bind( 'tcp://*:5555' ); // For clients

backend.bind( 'tcp://*:5556' ); // For workers

// Queue of available workers

workers := TZMQMsg.create;

poller := TZMQPoller.Create( true );

poller.Register( backend, [pePollIn] );

poller.Register( frontend, [pePollIn] );

// The body of this example is exactly the same as lbbroker2.

while not ctx.Terminated do

try

// Poll frontend only if we have available workers

if workers.size > 0 then

pc := 2

else

pc := 1;

poller.poll( 1000, pc );

// Handle worker activity on backend

if pePollIn in poller.PollItem[0].revents then

begin

// Use worker identity for load-balancing

backend.recv( msg );

identity := msg.unwrap;

workers.add( identity );

// Forward message to client if it's not a READY

frame := msg.first;

if frame.asUtf8String = WORKER_READY then

begin

msg.Free;

msg := nil;

end else

frontend.send( msg );

end;

if pePollIn in poller.PollItem[1].revents then

begin

// Get client request, route to first available worker

frontend.recv( msg );

msg.wrap( workers.pop );

backend.send( msg );

end;

except

end;

workers.Free;

ctx.Free;

end.

spqueue: Simple Pirate queue in Erlang

spqueue: Simple Pirate queue in Elixir

spqueue: Simple Pirate queue in F#

spqueue: Simple Pirate queue in Felix

spqueue: Simple Pirate queue in Go

// Simple Pirate broker

// This is identical to load-balancing pattern, with no reliability

// mechanisms. It depends on the client for recovery. Runs forever.

//

// Author: iano <scaly.iano@gmail.com>

// Based on C & Python example

package main

import (

zmq "github.com/alecthomas/gozmq"

)

const LRU_READY = "\001"

func main() {

context, _ := zmq.NewContext()

defer context.Close()

frontend, _ := context.NewSocket(zmq.ROUTER)

defer frontend.Close()

frontend.Bind("tcp://*:5555") // For clients

backend, _ := context.NewSocket(zmq.ROUTER)

defer backend.Close()

backend.Bind("tcp://*:5556") // For workers

// Queue of available workers

workers := make([][]byte, 0, 0)

for {

items := zmq.PollItems{

zmq.PollItem{Socket: backend, Events: zmq.POLLIN},

zmq.PollItem{Socket: frontend, Events: zmq.POLLIN},

}

// Poll frontend only if we have available workers

if len(workers) > 0 {

zmq.Poll(items, -1)

} else {

zmq.Poll(items[:1], -1)

}

// Handle worker activity on backend

if items[0].REvents&zmq.POLLIN != 0 {

// Use worker identity for load-balancing

msg, err := backend.RecvMultipart(0)

if err != nil {

panic(err) // Interrupted

}

address := msg[0]

workers = append(workers, address)

// Forward message to client if it's not a READY

if reply := msg[2:]; string(reply[0]) != LRU_READY {

frontend.SendMultipart(reply, 0)

}

}

if items[1].REvents&zmq.POLLIN != 0 {

// Get client request, route to first available worker

msg, err := frontend.RecvMultipart(0)

if err != nil {

panic(err) // Interrupted

}

last := workers[len(workers)-1]

workers = workers[:len(workers)-1]

request := append([][]byte{last, nil}, msg...)

backend.SendMultipart(request, 0)

}

}

}

spqueue: Simple Pirate queue in Haskell

{--

Simple Pirate queue in Haskell

--}

module Main where

import System.ZMQ4.Monadic

import Control.Concurrent (threadDelay)

import Control.Applicative ((<$>))

import Control.Monad (when)

import Data.ByteString.Char8 (pack, unpack, empty)

import Data.List (intercalate)

type SockID = String

workerReady = "\001"

main :: IO ()

main =

runZMQ $ do

frontend <- socket Router

bind frontend "tcp://*:5555"

backend <- socket Router

bind backend "tcp://*:5556"

pollPeers frontend backend []

pollPeers :: Socket z Router -> Socket z Router -> [SockID] -> ZMQ z ()

pollPeers frontend backend workers = do

let toPoll = getPollList workers

evts <- poll 0 toPoll

workers' <- getBackend backend frontend evts workers

workers'' <- getFrontend frontend backend evts workers'

pollPeers frontend backend workers''

where getPollList [] = [Sock backend [In] Nothing]

getPollList _ = [Sock backend [In] Nothing, Sock frontend [In] Nothing]

getBackend :: Socket z Router -> Socket z Router ->

[[Event]] -> [SockID] -> ZMQ z ([SockID])

getBackend backend frontend evts workers =

if (In `elem` (evts !! 0))

then do

wkrID <- receive backend

id <- (receive backend >> receive backend)

msg <- (receive backend >> receive backend)

when ((unpack msg) /= workerReady) $ do

liftIO $ putStrLn $ "I: sending backend - " ++ (unpack msg)

send frontend [SendMore] id

send frontend [SendMore] empty

send frontend [] msg

return $ (unpack wkrID):workers

else return workers

getFrontend :: Socket z Router -> Socket z Router ->

[[Event]] -> [SockID] -> ZMQ z [SockID]

getFrontend frontend backend evts workers =

if (length evts > 1 && In `elem` (evts !! 1))

then do

id <- receive frontend

msg <- (receive frontend >> receive frontend)

liftIO $ putStrLn $ "I: msg on frontend - " ++ (unpack msg)

let wkrID = head workers

send backend [SendMore] (pack wkrID)

send backend [SendMore] empty

send backend [SendMore] id

send backend [SendMore] empty

send backend [] msg

return $ tail workers

else return workers

spqueue: Simple Pirate queue in Haxe

package ;

import haxe.Stack;

import neko.Lib;

import org.zeromq.ZFrame;

import org.zeromq.ZContext;

import org.zeromq.ZMQSocket;

import org.zeromq.ZMQPoller;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ;

import org.zeromq.ZMsg;

import org.zeromq.ZMQException;

/**

* Simple Pirate queue

* This is identical to the LRU pattern, with no reliability mechanisms

* at all. It depends on the client for recovery. Runs forever.

*

* @see http://zguide.zeromq.org/page:all#Basic-Reliable-Queuing-Simple-Pirate-Pattern

*/

class SPQueue

{

// Signals workers are ready

private static inline var LRU_READY:String = String.fromCharCode(1);

public static function main() {

Lib.println("** SPQueue (see: http://zguide.zeromq.org/page:all#Basic-Reliable-Queuing-Simple-Pirate-Pattern)");

// Prepare our context and sockets

var context:ZContext = new ZContext();

var frontend:ZMQSocket = context.createSocket(ZMQ_ROUTER);

var backend:ZMQSocket = context.createSocket(ZMQ_ROUTER);

frontend.bind("tcp://*:5555"); // For clients

backend.bind("tcp://*:5556"); // For workers

// Queue of available workers

var workerQueue:List<ZFrame> = new List<ZFrame>();

var poller:ZMQPoller = new ZMQPoller();

poller.registerSocket(backend, ZMQ.ZMQ_POLLIN());

while (true) {

poller.unregisterSocket(frontend);

if (workerQueue.length > 0) {

// Only poll frontend if there is at least 1 worker ready to do work

poller.registerSocket(frontend, ZMQ.ZMQ_POLLIN());

}

try {

poller.poll( -1 );

} catch (e:ZMQException) {

if (ZMQ.isInterrupted())

break;

trace("ZMQException #:" + e.errNo + ", str:" + e.str());

trace (Stack.toString(Stack.exceptionStack()));

}

if (poller.pollin(1)) {

// Use worker address for LRU routing

var msg = ZMsg.recvMsg(backend);

if (msg == null)

break; // Interrupted

var address = msg.unwrap();

workerQueue.add(address);

// Forward message to client if it's not a READY

var frame = msg.first();

if (frame.streq(LRU_READY))

msg.destroy();

else

msg.send(frontend);

}

if (poller.pollin(2)) {

// Get client request, route to first available worker

var msg = ZMsg.recvMsg(frontend);

if (msg != null) {

msg.wrap(workerQueue.pop());

msg.send(backend);

}

}

}

// When we're done, clean up properly

for (f in workerQueue) {

f.destroy();

}

context.destroy();

}

}spqueue: Simple Pirate queue in Java

package guide;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import org.zeromq.*;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ.Poller;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ.Socket;

//

// Simple Pirate queue

// This is identical to load-balancing pattern, with no reliability mechanisms

// at all. It depends on the client for recovery. Runs forever.

//

public class spqueue

{

private final static String WORKER_READY = "\001"; // Signals worker is ready

public static void main(String[] args)

{

try (ZContext ctx = new ZContext()) {

Socket frontend = ctx.createSocket(SocketType.ROUTER);

Socket backend = ctx.createSocket(SocketType.ROUTER);

frontend.bind("tcp://*:5555"); // For clients

backend.bind("tcp://*:5556"); // For workers

// Queue of available workers

ArrayList<ZFrame> workers = new ArrayList<ZFrame>();

Poller poller = ctx.createPoller(2);

poller.register(backend, Poller.POLLIN);

poller.register(frontend, Poller.POLLIN);

// The body of this example is exactly the same as lruqueue2.

while (true) {

boolean workersAvailable = workers.size() > 0;

int rc = poller.poll(-1);

// Poll frontend only if we have available workers

if (rc == -1)

break; // Interrupted

// Handle worker activity on backend

if (poller.pollin(0)) {

// Use worker address for LRU routing

ZMsg msg = ZMsg.recvMsg(backend);

if (msg == null)

break; // Interrupted

ZFrame address = msg.unwrap();

workers.add(address);

// Forward message to client if it's not a READY

ZFrame frame = msg.getFirst();

if (new String(frame.getData(), ZMQ.CHARSET).equals(WORKER_READY))

msg.destroy();

else msg.send(frontend);

}

if (workersAvailable && poller.pollin(1)) {

// Get client request, route to first available worker

ZMsg msg = ZMsg.recvMsg(frontend);

if (msg != null) {

msg.wrap(workers.remove(0));

msg.send(backend);

}

}

}

// When we're done, clean up properly

while (workers.size() > 0) {

ZFrame frame = workers.remove(0);

frame.destroy();

}

workers.clear();

}

}

}

spqueue: Simple Pirate queue in Julia

spqueue: Simple Pirate queue in Lua

--

-- Simple Pirate queue

-- This is identical to the LRU pattern, with no reliability mechanisms

-- at all. It depends on the client for recovery. Runs forever.

--

-- Author: Robert G. Jakabosky <bobby@sharedrealm.com>

--

require"zmq"