Chapter 5 - Advanced Pub-Sub Patterns #

In Chapter 3 - Advanced Request-Reply Patterns and Chapter 4 - Reliable Request-Reply Patterns we looked at advanced use of ZeroMQ’s request-reply pattern. If you managed to digest all that, congratulations. In this chapter we’ll focus on publish-subscribe and extend ZeroMQ’s core pub-sub pattern with higher-level patterns for performance, reliability, state distribution, and monitoring.

We’ll cover:

- When to use publish-subscribe

- How to handle too-slow subscribers (the Suicidal Snail pattern)

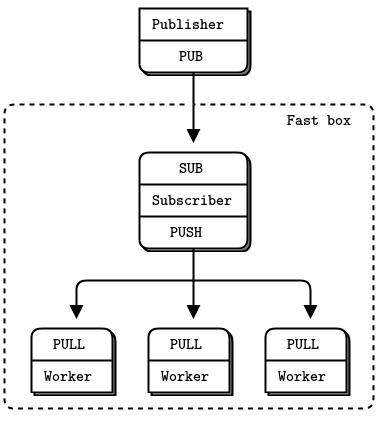

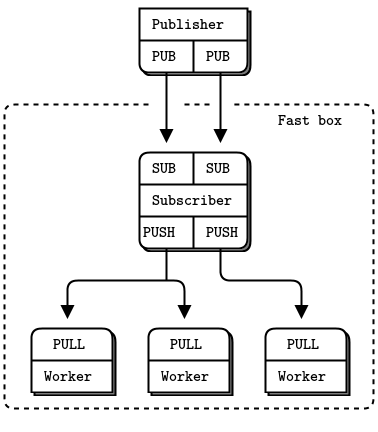

- How to design high-speed subscribers (the Black Box pattern)

- How to monitor a pub-sub network (the Espresso pattern)

- How to build a shared key-value store (the Clone pattern)

- How to use reactors to simplify complex servers

- How to use the Binary Star pattern to add failover to a server

Pros and Cons of Pub-Sub #

ZeroMQ’s low-level patterns have their different characters. Pub-sub addresses an old messaging problem, which is multicast or group messaging. It has that unique mix of meticulous simplicity and brutal indifference that characterizes ZeroMQ. It’s worth understanding the trade-offs that pub-sub makes, how these benefit us, and how we can work around them if needed.

First, PUB sends each message to “all of many”, whereas PUSH and DEALER rotate messages to “one of many”. You cannot simply replace PUSH with PUB or vice versa and hope that things will work. This bears repeating because people seem to quite often suggest doing this.

More profoundly, pub-sub is aimed at scalability. This means large volumes of data, sent rapidly to many recipients. If you need millions of messages per second sent to thousands of points, you’ll appreciate pub-sub a lot more than if you need a few messages a second sent to a handful of recipients.

To get scalability, pub-sub uses the same trick as push-pull, which is to get rid of back-chatter. This means that recipients don’t talk back to senders. There are some exceptions, e.g., SUB sockets will send subscriptions to PUB sockets, but it’s anonymous and infrequent.

Killing back-chatter is essential to real scalability. With pub-sub, it’s how the pattern can map cleanly to the PGM multicast protocol, which is handled by the network switch. In other words, subscribers don’t connect to the publisher at all, they connect to a multicast group on the switch, to which the publisher sends its messages.

When we remove back-chatter, our overall message flow becomes much simpler, which lets us make simpler APIs, simpler protocols, and in general reach many more people. But we also remove any possibility to coordinate senders and receivers. What this means is:

-

Publishers can’t tell when subscribers are successfully connected, both on initial connections, and on reconnections after network failures.

-

Subscribers can’t tell publishers anything that would allow publishers to control the rate of messages they send. Publishers only have one setting, which is full-speed, and subscribers must either keep up or lose messages.

-

Publishers can’t tell when subscribers have disappeared due to processes crashing, networks breaking, and so on.

The downside is that we actually need all of these if we want to do reliable multicast. The ZeroMQ pub-sub pattern will lose messages arbitrarily when a subscriber is connecting, when a network failure occurs, or just if the subscriber or network can’t keep up with the publisher.

The upside is that there are many use cases where almost reliable multicast is just fine. When we need this back-chatter, we can either switch to using ROUTER-DEALER (which I tend to do for most normal volume cases), or we can add a separate channel for synchronization (we’ll see an example of this later in this chapter).

Pub-sub is like a radio broadcast; you miss everything before you join, and then how much information you get depends on the quality of your reception. Surprisingly, this model is useful and widespread because it maps perfectly to real world distribution of information. Think of Facebook and Twitter, the BBC World Service, and the sports results.

As we did for request-reply, let’s define reliability in terms of what can go wrong. Here are the classic failure cases for pub-sub:

- Subscribers join late, so they miss messages the server already sent.

- Subscribers can fetch messages too slowly, so queues build up and then overflow.

- Subscribers can drop off and lose messages while they are away.

- Subscribers can crash and restart, and lose whatever data they already received.

- Networks can become overloaded and drop data (specifically, for PGM).

- Networks can become too slow, so publisher-side queues overflow and publishers crash.

A lot more can go wrong but these are the typical failures we see in a realistic system. Since v3.x, ZeroMQ forces default limits on its internal buffers (the so-called high-water mark or HWM), so publisher crashes are rarer unless you deliberately set the HWM to infinite.

All of these failure cases have answers, though not always simple ones. Reliability requires complexity that most of us don’t need, most of the time, which is why ZeroMQ doesn’t attempt to provide it out of the box (even if there was one global design for reliability, which there isn’t).

Pub-Sub Tracing (Espresso Pattern) #

Let’s start this chapter by looking at a way to trace pub-sub networks. In Chapter 2 - Sockets and Patterns we saw a simple proxy that used these to do transport bridging. The zmq_proxy() method has three arguments: a frontend and backend socket that it bridges together, and a capture socket to which it will send all messages.

The code is deceptively simple:

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Ada

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Basic

espresso: Espresso Pattern in C

// Espresso Pattern

// This shows how to capture data using a pub-sub proxy

#include "czmq.h"

// The subscriber thread requests messages starting with

// A and B, then reads and counts incoming messages.

static void

subscriber_thread (void *args, zctx_t *ctx, void *pipe)

{

// Subscribe to "A" and "B"

void *subscriber = zsocket_new (ctx, ZMQ_SUB);

zsocket_connect (subscriber, "tcp://localhost:6001");

zsocket_set_subscribe (subscriber, "A");

zsocket_set_subscribe (subscriber, "B");

int count = 0;

while (count < 5) {

char *string = zstr_recv (subscriber);

if (!string)

break; // Interrupted

free (string);

count++;

}

zsocket_destroy (ctx, subscriber);

}

// .split publisher thread

// The publisher sends random messages starting with A-J:

static void

publisher_thread (void *args, zctx_t *ctx, void *pipe)

{

void *publisher = zsocket_new (ctx, ZMQ_PUB);

zsocket_bind (publisher, "tcp://*:6000");

while (!zctx_interrupted) {

char string [10];

sprintf (string, "%c-%05d", randof (10) + 'A', randof (100000));

if (zstr_send (publisher, string) == -1)

break; // Interrupted

zclock_sleep (100); // Wait for 1/10th second

}

}

// .split listener thread

// The listener receives all messages flowing through the proxy, on its

// pipe. In CZMQ, the pipe is a pair of ZMQ_PAIR sockets that connect

// attached child threads. In other languages your mileage may vary:

static void

listener_thread (void *args, zctx_t *ctx, void *pipe)

{

// Print everything that arrives on pipe

while (true) {

zframe_t *frame = zframe_recv (pipe);

if (!frame)

break; // Interrupted

zframe_print (frame, NULL);

zframe_destroy (&frame);

}

}

// .split main thread

// The main task starts the subscriber and publisher, and then sets

// itself up as a listening proxy. The listener runs as a child thread:

int main (void)

{

// Start child threads

zctx_t *ctx = zctx_new ();

zthread_fork (ctx, publisher_thread, NULL);

zthread_fork (ctx, subscriber_thread, NULL);

void *subscriber = zsocket_new (ctx, ZMQ_XSUB);

zsocket_connect (subscriber, "tcp://localhost:6000");

void *publisher = zsocket_new (ctx, ZMQ_XPUB);

zsocket_bind (publisher, "tcp://*:6001");

void *listener = zthread_fork (ctx, listener_thread, NULL);

zmq_proxy (subscriber, publisher, listener);

puts (" interrupted");

// Tell attached threads to exit

zctx_destroy (&ctx);

return 0;

}

espresso: Espresso Pattern in C++

#include <iostream>

#include <thread>

#include <zmq.hpp>

#include <string>

#include <chrono>

#include <unistd.h>

// Subscriber thread function

void subscriber_thread(zmq::context_t& ctx) {

zmq::socket_t subscriber(ctx, ZMQ_SUB);

subscriber.connect("tcp://localhost:6001");

subscriber.set(zmq::sockopt::subscribe, "A");

subscriber.set(zmq::sockopt::subscribe, "B");

int count = 0;

while (count < 5) {

zmq::message_t message;

if (subscriber.recv(message)) {

std::string msg = std::string((char*)(message.data()), message.size());

std::cout << "Received: " << msg << std::endl;

count++;

}

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::milliseconds(100));

}

}

// Publisher thread function

void publisher_thread(zmq::context_t& ctx) {

zmq::socket_t publisher(ctx, ZMQ_PUB);

publisher.bind("tcp://*:6000");

while (true) {

char string[10];

sprintf(string, "%c-%05d", rand() % 10 + 'A', rand() % 100000);

zmq::message_t message(string, strlen(string));

publisher.send(message, zmq::send_flags::none);

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::milliseconds(100));

}

}

// Listener thread function

void listener_thread(zmq::context_t& ctx) {

zmq::socket_t listener(ctx, ZMQ_PAIR);

listener.connect("inproc://listener");

while (true) {

zmq::message_t message;

if (listener.recv(message)) {

std::string msg = std::string((char*)(message.data()), message.size());

std::cout << "Listener Received: ";

if (msg[0] == 0 || msg[0] == 1){

std::cout << int(msg[0]);

std::cout << msg[1]<< std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << msg << std::endl;

}

}

}

}

int main() {

zmq::context_t context(1);

// Main thread acts as the listener proxy

zmq::socket_t proxy(context, ZMQ_PAIR);

proxy.bind("inproc://listener");

zmq::socket_t xsub(context, ZMQ_XSUB);

zmq::socket_t xpub(context, ZMQ_XPUB);

xpub.bind("tcp://*:6001");

sleep(1);

// Start publisher and subscriber threads

std::thread pub_thread(publisher_thread, std::ref(context));

std::thread sub_thread(subscriber_thread, std::ref(context));

// Set up listener thread

std::thread lis_thread(listener_thread, std::ref(context));

sleep(1);

xsub.connect("tcp://localhost:6000");

// Proxy messages between SUB and PUB sockets

zmq_proxy(xsub, xpub, proxy);

// Wait for threads to finish

pub_thread.join();

sub_thread.join();

lis_thread.join();

return 0;

}

espresso: Espresso Pattern in C#

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using System.Text;

using System.Threading;

using ZeroMQ;

namespace Examples

{

static partial class Program

{

public static void Espresso(string[] args)

{

//

// Espresso Pattern

// This shows how to capture data using a pub-sub proxy

//

// Author: metadings

//

using (var context = new ZContext())

using (var subscriber = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.XSUB))

using (var publisher = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.XPUB))

using (var listener = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.PAIR))

{

new Thread(() => Espresso_Publisher(context)).Start();

new Thread(() => Espresso_Subscriber(context)).Start();

new Thread(() => Espresso_Listener(context)).Start();

subscriber.Connect("tcp://127.0.0.1:6000");

publisher.Bind("tcp://*:6001");

listener.Bind("inproc://listener");

ZError error;

if (!ZContext.Proxy(subscriber, publisher, listener, out error))

{

if (error == ZError.ETERM)

return; // Interrupted

throw new ZException(error);

}

}

}

static void Espresso_Publisher(ZContext context)

{

// The publisher sends random messages starting with A-J:

using (var publisher = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.PUB))

{

publisher.Bind("tcp://*:6000");

ZError error;

while (true)

{

var frame = ZFrame.Create(8);

var bytes = new byte[8];

using (var rng = new System.Security.Cryptography.RNGCryptoServiceProvider())

{

rng.GetBytes(bytes);

}

frame.Write(bytes, 0, 8);

if (!publisher.SendFrame(frame, out error))

{

if (error == ZError.ETERM)

return; // Interrupted

throw new ZException(error);

}

Thread.Sleep(1);

}

}

}

static void Espresso_Subscriber(ZContext context)

{

// The subscriber thread requests messages starting with

// A and B, then reads and counts incoming messages.

using (var subscriber = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.SUB))

{

subscriber.Connect("tcp://127.0.0.1:6001");

subscriber.Subscribe("A");

subscriber.Subscribe("B");

ZError error;

ZFrame frame;

int count = 0;

while (count < 5)

{

if (null == (frame = subscriber.ReceiveFrame(out error)))

{

if (error == ZError.ETERM)

return; // Interrupted

throw new ZException(error);

}

++count;

}

Console.WriteLine("I: subscriber counted {0}", count);

}

}

static void Espresso_Listener(ZContext context)

{

// The listener receives all messages flowing through the proxy, on its

// pipe. In CZMQ, the pipe is a pair of ZMQ_PAIR sockets that connect

// attached child threads. In other languages your mileage may vary:

using (var listener = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.PAIR))

{

listener.Connect("inproc://listener");

ZError error;

ZFrame frame;

while (true)

{

if (null != (frame = listener.ReceiveFrame(out error)))

{

using (frame)

{

byte first = frame.ReadAsByte();

var rest = new byte[9];

frame.Read(rest, 0, rest.Length);

Console.WriteLine("{0} {1}", (char)first, rest.ToHexString());

if (first == 0x01)

{

// Subscribe

}

else if (first == 0x00)

{

// Unsubscribe

context.Shutdown();

}

}

}

else

{

if (error == ZError.ETERM)

return; // Interrupted

throw new ZException(error);

}

}

}

}

}

}

espresso: Espresso Pattern in CL

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Delphi

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Erlang

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Elixir

espresso: Espresso Pattern in F#

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Felix

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Go

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Haskell

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Haxe

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Java

package guide;

import java.util.Random;

import org.zeromq.*;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ.Socket;

import org.zeromq.ZThread.IAttachedRunnable;

// Espresso Pattern

// This shows how to capture data using a pub-sub proxy

public class espresso

{

// The subscriber thread requests messages starting with

// A and B, then reads and counts incoming messages.

private static class Subscriber implements IAttachedRunnable

{

@Override

public void run(Object[] args, ZContext ctx, Socket pipe)

{

// Subscribe to "A" and "B"

Socket subscriber = ctx.createSocket(SocketType.SUB);

subscriber.connect("tcp://localhost:6001");

subscriber.subscribe("A".getBytes(ZMQ.CHARSET));

subscriber.subscribe("B".getBytes(ZMQ.CHARSET));

int count = 0;

while (count < 5) {

String string = subscriber.recvStr();

if (string == null)

break; // Interrupted

count++;

}

ctx.destroySocket(subscriber);

}

}

// .split publisher thread

// The publisher sends random messages starting with A-J:

private static class Publisher implements IAttachedRunnable

{

@Override

public void run(Object[] args, ZContext ctx, Socket pipe)

{

Socket publisher = ctx.createSocket(SocketType.PUB);

publisher.bind("tcp://*:6000");

Random rand = new Random(System.currentTimeMillis());

while (!Thread.currentThread().isInterrupted()) {

String string = String.format("%c-%05d", 'A' + rand.nextInt(10), rand.nextInt(100000));

if (!publisher.send(string))

break; // Interrupted

try {

Thread.sleep(100); // Wait for 1/10th second

}

catch (InterruptedException e) {

}

}

ctx.destroySocket(publisher);

}

}

// .split listener thread

// The listener receives all messages flowing through the proxy, on its

// pipe. In CZMQ, the pipe is a pair of ZMQ_PAIR sockets that connect

// attached child threads. In other languages your mileage may vary:

private static class Listener implements IAttachedRunnable

{

@Override

public void run(Object[] args, ZContext ctx, Socket pipe)

{

// Print everything that arrives on pipe

while (true) {

ZFrame frame = ZFrame.recvFrame(pipe);

if (frame == null)

break; // Interrupted

frame.print(null);

frame.destroy();

}

}

}

// .split main thread

// The main task starts the subscriber and publisher, and then sets

// itself up as a listening proxy. The listener runs as a child thread:

public static void main(String[] argv)

{

try (ZContext ctx = new ZContext()) {

// Start child threads

ZThread.fork(ctx, new Publisher());

ZThread.fork(ctx, new Subscriber());

Socket subscriber = ctx.createSocket(SocketType.XSUB);

subscriber.connect("tcp://localhost:6000");

Socket publisher = ctx.createSocket(SocketType.XPUB);

publisher.bind("tcp://*:6001");

Socket listener = ZThread.fork(ctx, new Listener());

ZMQ.proxy(subscriber, publisher, listener);

System.out.println(" interrupted");

// NB: child threads exit here when the context is closed

}

}

}

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Julia

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Lua

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Node.js

/**

* Pub-Sub Tracing (Espresso Pattern)

* explained in

* https://zguide.zeromq.org/docs/chapter5

*/

"use strict";

Object.defineProperty(exports, "__esModule", { value: true });

exports.runListenerThread = exports.runPubThread = exports.runSubThread = void 0;

const zmq = require("zeromq"),

publisher = new zmq.Publisher,

pubKeypair = zmq.curveKeyPair(),

publicKey = pubKeypair.publicKey;

var interrupted = false;

function getRandomInt(max) {

return Math.floor(Math.random() * Math.floor(max));

}

async function runSubThread() {

const subscriber = new zmq.Subscriber;

const subKeypair = zmq.curveKeyPair();

// Setup encryption.

for (const s of [subscriber]) {

subscriber.curveServerKey = publicKey; // '03P+E+f4AU6bSTcuzvgX&oGnt&Or<rN)FYIPyjQW'

subscriber.curveSecretKey = subKeypair.secretKey;

subscriber.curvePublicKey = subKeypair.publicKey;

}

await subscriber.connect("tcp://127.0.0.1:6000");

console.log('subscriber connected! subscribing A,B,C and D..');

//subscribe all at once - simultaneous subscriptions needed

Promise.all([

subscriber.subscribe("A"),

subscriber.subscribe("B"),

subscriber.subscribe("C"),

subscriber.subscribe("D"),

subscriber.subscribe("E"),

]);

for await (const [msg] of subscriber) {

console.log(`Received at subscriber: ${msg}`);

if (interrupted) {

await subscriber.disconnect("tcp://127.0.0.1:6000");

await subscriber.close();

break;

}

}

}

//Run the Publisher Thread!

async function runPubThread() {

// Setup encryption.

for (const s of [publisher]) {

s.curveServer = true;

s.curvePublicKey = publicKey;

s.curveSecretKey = pubKeypair.secretKey;

}

await publisher.bind("tcp://127.0.0.1:6000");

console.log(`Started publisher at tcp://127.0.0.1:6000 ..`);

var subs = 'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789';

while (!interrupted) { //until ctl+c

var str = `${subs.charAt(getRandomInt(10))}-${getRandomInt(100000).toString().padStart(6, '0')}`; //"%c-%05d";

console.log(`Publishing ${str}`);

if (-1 == await publisher.send(str))

break; //Interrupted

await new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(resolve, 1000));

}

//if(! publisher.closed())

await publisher.close();

}

//Run the Pipe

async function runListenerThread() {

//a pipe using 'Pair' which receives and transmits data

const pipe = new zmq.Pair;

await pipe.connect("tcp://127.0.0.1:6000");

await pipe.bind("tcp://127.0.0.1:6001");

console.log('starting pipe (using Pair)..');

while (!interrupted) {

await pipe.send(await pipe.receive());

}

setTimeout(() => {

console.log('Terminating pipe..');

pipe.close();

}, 1000);

//a pipe using 'Proxy' <= not working, but give it a try.

// Still working with Proxy

/*

const pipe = new zmq.Proxy (new zmq.Router, new zmq.Dealer)

await pipe.backEnd.connect("tcp://127.0.0.1:6000")

await pipe.frontEnd.bind("tcp://127.0.0.1:6001")

await pipe.run()

setTimeout(() => {

console.log('Terminating pipe..');

await pipe.terminate()

}, 10000);

*/

}

exports.runSubThread = runSubThread;

exports.runPubThread = runPubThread;

exports.runListenerThread = runListenerThread;

process.on('SIGINT', function () {

interrupted = true;

});

process.setMaxListeners(30);

async function main() {

//execute all at once

Promise.all([

runPubThread(),

runListenerThread(),

runSubThread(),

]);

}

main().catch(err => {

console.error(err);

process.exit(1);

});

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Objective-C

espresso: Espresso Pattern in ooc

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Perl

espresso: Espresso Pattern in PHP

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Python

# Espresso Pattern

# This shows how to capture data using a pub-sub proxy

#

import time

from random import randint

from string import ascii_uppercase as uppercase

from threading import Thread

import zmq

from zmq.devices import monitored_queue

from zhelpers import zpipe

# The subscriber thread requests messages starting with

# A and B, then reads and counts incoming messages.

def subscriber_thread():

ctx = zmq.Context.instance()

# Subscribe to "A" and "B"

subscriber = ctx.socket(zmq.SUB)

subscriber.connect("tcp://localhost:6001")

subscriber.setsockopt(zmq.SUBSCRIBE, b"A")

subscriber.setsockopt(zmq.SUBSCRIBE, b"B")

count = 0

while count < 5:

try:

msg = subscriber.recv_multipart()

except zmq.ZMQError as e:

if e.errno == zmq.ETERM:

break # Interrupted

else:

raise

count += 1

print ("Subscriber received %d messages" % count)

# publisher thread

# The publisher sends random messages starting with A-J:

def publisher_thread():

ctx = zmq.Context.instance()

publisher = ctx.socket(zmq.PUB)

publisher.bind("tcp://*:6000")

while True:

string = "%s-%05d" % (uppercase[randint(0,10)], randint(0,100000))

try:

publisher.send(string.encode('utf-8'))

except zmq.ZMQError as e:

if e.errno == zmq.ETERM:

break # Interrupted

else:

raise

time.sleep(0.1) # Wait for 1/10th second

# listener thread

# The listener receives all messages flowing through the proxy, on its

# pipe. Here, the pipe is a pair of ZMQ_PAIR sockets that connects

# attached child threads via inproc. In other languages your mileage may vary:

def listener_thread (pipe):

# Print everything that arrives on pipe

while True:

try:

print (pipe.recv_multipart())

except zmq.ZMQError as e:

if e.errno == zmq.ETERM:

break # Interrupted

# main thread

# The main task starts the subscriber and publisher, and then sets

# itself up as a listening proxy. The listener runs as a child thread:

def main ():

# Start child threads

ctx = zmq.Context.instance()

p_thread = Thread(target=publisher_thread)

s_thread = Thread(target=subscriber_thread)

p_thread.start()

s_thread.start()

pipe = zpipe(ctx)

subscriber = ctx.socket(zmq.XSUB)

subscriber.connect("tcp://localhost:6000")

publisher = ctx.socket(zmq.XPUB)

publisher.bind("tcp://*:6001")

l_thread = Thread(target=listener_thread, args=(pipe[1],))

l_thread.start()

try:

monitored_queue(subscriber, publisher, pipe[0], b'pub', b'sub')

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print ("Interrupted")

del subscriber, publisher, pipe

ctx.term()

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Q

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Racket

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Ruby

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Rust

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Scala

espresso: Espresso Pattern in Tcl

espresso: Espresso Pattern in OCaml

Espresso works by creating a listener thread that reads a PAIR socket and prints anything it gets. That PAIR socket is one end of a pipe; the other end (another PAIR) is the socket we pass to zmq_proxy(). In practice, you’d filter interesting messages to get the essence of what you want to track (hence the name of the pattern).

The subscriber thread subscribes to “A” and “B”, receives five messages, and then destroys its socket. When you run the example, the listener prints two subscription messages, five data messages, two unsubscribe messages, and then silence:

[002] 0141

[002] 0142

[007] B-91164

[007] B-12979

[007] A-52599

[007] A-06417

[007] A-45770

[002] 0041

[002] 0042

This shows neatly how the publisher socket stops sending data when there are no subscribers for it. The publisher thread is still sending messages. The socket just drops them silently.

Last Value Caching #

If you’ve used commercial pub-sub systems, you may be used to some features that are missing in the fast and cheerful ZeroMQ pub-sub model. One of these is last value caching (LVC). This solves the problem of how a new subscriber catches up when it joins the network. The theory is that publishers get notified when a new subscriber joins and subscribes to some specific topics. The publisher can then rebroadcast the last message for those topics.

I’ve already explained why publishers don’t get notified when there are new subscribers, because in large pub-sub systems, the volumes of data make it pretty much impossible. To make really large-scale pub-sub networks, you need a protocol like PGM that exploits an upscale Ethernet switch’s ability to multicast data to thousands of subscribers. Trying to do a TCP unicast from the publisher to each of thousands of subscribers just doesn’t scale. You get weird spikes, unfair distribution (some subscribers getting the message before others), network congestion, and general unhappiness.

PGM is a one-way protocol: the publisher sends a message to a multicast address at the switch, which then rebroadcasts that to all interested subscribers. The publisher never sees when subscribers join or leave: this all happens in the switch, which we don’t really want to start reprogramming.

However, in a lower-volume network with a few dozen subscribers and a limited number of topics, we can use TCP and then the XSUB and XPUB sockets do talk to each other as we just saw in the Espresso pattern.

Can we make an LVC using ZeroMQ? The answer is yes, if we make a proxy that sits between the publisher and subscribers; an analog for the PGM switch, but one we can program ourselves.

I’ll start by making a publisher and subscriber that highlight the worst case scenario. This publisher is pathological. It starts by immediately sending messages to each of a thousand topics, and then it sends one update a second to a random topic. A subscriber connects, and subscribes to a topic. Without LVC, a subscriber would have to wait an average of 500 seconds to get any data. To add some drama, let’s pretend there’s an escaped convict called Gregor threatening to rip the head off Roger the toy bunny if we can’t fix that 8.3 minutes’ delay.

Here’s the publisher code. Note that it has the command line option to connect to some address, but otherwise binds to an endpoint. We’ll use this later to connect to our last value cache:

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Ada

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Basic

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in C

// Pathological publisher

// Sends out 1,000 topics and then one random update per second

#include "czmq.h"

int main (int argc, char *argv [])

{

zctx_t *context = zctx_new ();

void *publisher = zsocket_new (context, ZMQ_PUB);

if (argc == 2)

zsocket_bind (publisher, argv [1]);

else

zsocket_bind (publisher, "tcp://*:5556");

// Ensure subscriber connection has time to complete

sleep (1);

// Send out all 1,000 topic messages

int topic_nbr;

for (topic_nbr = 0; topic_nbr < 1000; topic_nbr++) {

zstr_sendfm (publisher, "%03d", topic_nbr);

zstr_send (publisher, "Save Roger");

}

// Send one random update per second

srandom ((unsigned) time (NULL));

while (!zctx_interrupted) {

sleep (1);

zstr_sendfm (publisher, "%03d", randof (1000));

zstr_send (publisher, "Off with his head!");

}

zctx_destroy (&context);

return 0;

}

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in C++

// Pathological publisher

// Sends out 1,000 topics and then one random update per second

#include <thread>

#include <chrono>

#include "zhelpers.hpp"

int main (int argc, char *argv [])

{

zmq::context_t context(1);

zmq::socket_t publisher(context, ZMQ_PUB);

// Initialize random number generator

srandom ((unsigned) time (NULL));

if (argc == 2)

publisher.bind(argv [1]);

else

publisher.bind("tcp://*:5556");

// Ensure subscriber connection has time to complete

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::seconds(1));

// Send out all 1,000 topic messages

int topic_nbr;

for (topic_nbr = 0; topic_nbr < 1000; topic_nbr++) {

std::stringstream ss;

ss << std::dec << std::setw(3) << std::setfill('0') << topic_nbr;

s_sendmore (publisher, ss.str());

s_send (publisher, std::string("Save Roger"));

}

// Send one random update per second

while (1) {

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::seconds(1));

std::stringstream ss;

ss << std::dec << std::setw(3) << std::setfill('0') << within(1000);

s_sendmore (publisher, ss.str());

s_send (publisher, std::string("Off with his head!"));

}

return 0;

}

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in C#

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using System.Text;

using System.Threading;

using ZeroMQ;

namespace Examples

{

static partial class Program

{

public static void PathoPub(string[] args)

{

//

// Pathological publisher

// Sends out 1,000 topics and then one random update per second

//

// Author: metadings

//

if (args == null || args.Length < 1)

{

Console.WriteLine();

Console.WriteLine("Usage: ./{0} PathoPub [Endpoint]", AppDomain.CurrentDomain.FriendlyName);

Console.WriteLine();

Console.WriteLine(" Endpoint Where PathoPub should connect to.");

Console.WriteLine(" Default is null, Binding on tcp://*:5556");

Console.WriteLine();

args = new string[] { null };

}

using (var context = new ZContext())

using (var publisher = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.PUB))

{

if (args[0] != null)

{

publisher.Connect(args[0]);

}

else

{

publisher.Bind("tcp://*:5556");

}

// Ensure subscriber connection has time to complete

Thread.Sleep(100);

// Send out all 1,000 topic messages

for (int topic = 0; topic < 1000; ++topic)

{

publisher.SendMore(new ZFrame(string.Format("{0:D3}", topic)));

publisher.Send(new ZFrame("Save Roger"));

}

// Send one random update per second

var rnd = new Random();

while (true)

{

Thread.Sleep(10);

publisher.SendMore(new ZFrame(string.Format("{0:D3}", rnd.Next(1000))));

publisher.Send(new ZFrame("Off with his head!"));

}

}

}

}

}

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in CL

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Delphi

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Erlang

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Elixir

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in F#

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Felix

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Go

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Haskell

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Haxe

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Java

package guide;

import java.util.Random;

import org.zeromq.SocketType;

import org.zeromq.ZContext;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ.Socket;

// Pathological publisher

// Sends out 1,000 topics and then one random update per second

public class pathopub

{

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception

{

try (ZContext context = new ZContext()) {

Socket publisher = context.createSocket(SocketType.PUB);

if (args.length == 1)

publisher.connect(args[0]);

else publisher.bind("tcp://*:5556");

// Ensure subscriber connection has time to complete

Thread.sleep(1000);

// Send out all 1,000 topic messages

int topicNbr;

for (topicNbr = 0; topicNbr < 1000; topicNbr++) {

publisher.send(String.format("%03d", topicNbr), ZMQ.SNDMORE);

publisher.send("Save Roger");

}

// Send one random update per second

Random rand = new Random(System.currentTimeMillis());

while (!Thread.currentThread().isInterrupted()) {

Thread.sleep(1000);

publisher.send(

String.format("%03d", rand.nextInt(1000)), ZMQ.SNDMORE

);

publisher.send("Off with his head!");

}

}

}

}

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Julia

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Lua

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Node.js

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Objective-C

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in ooc

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Perl

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in PHP

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Python

#

# Pathological publisher

# Sends out 1,000 topics and then one random update per second

#

import sys

import time

from random import randint

import zmq

def main(url=None):

ctx = zmq.Context.instance()

publisher = ctx.socket(zmq.PUB)

if url:

publisher.bind(url)

else:

publisher.bind("tcp://*:5556")

# Ensure subscriber connection has time to complete

time.sleep(1)

# Send out all 1,000 topic messages

for topic_nbr in range(1000):

publisher.send_multipart([

b"%03d" % topic_nbr,

b"Save Roger",

])

while True:

# Send one random update per second

try:

time.sleep(1)

publisher.send_multipart([

b"%03d" % randint(0,999),

b"Off with his head!",

])

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print "interrupted"

break

if __name__ == '__main__':

main(sys.argv[1] if len(sys.argv) > 1 else None)

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Q

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Racket

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Ruby

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Rust

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Scala

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in Tcl

pathopub: Pathologic Publisher in OCaml

And here’s the subscriber:

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Ada

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Basic

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in C

// Pathological subscriber

// Subscribes to one random topic and prints received messages

#include "czmq.h"

int main (int argc, char *argv [])

{

zctx_t *context = zctx_new ();

void *subscriber = zsocket_new (context, ZMQ_SUB);

if (argc == 2)

zsocket_connect (subscriber, argv [1]);

else

zsocket_connect (subscriber, "tcp://localhost:5556");

srandom ((unsigned) time (NULL));

char subscription [5];

sprintf (subscription, "%03d", randof (1000));

zsocket_set_subscribe (subscriber, subscription);

while (true) {

char *topic = zstr_recv (subscriber);

if (!topic)

break;

char *data = zstr_recv (subscriber);

assert (streq (topic, subscription));

puts (data);

free (topic);

free (data);

}

zctx_destroy (&context);

return 0;

}

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in C++

// Pathological subscriber

// Subscribes to one random topic and prints received messages

#include "zhelpers.hpp"

int main (int argc, char *argv [])

{

zmq::context_t context(1);

zmq::socket_t subscriber (context, ZMQ_SUB);

// Initialize random number generator

srandom ((unsigned) time (NULL));

if (argc == 2)

subscriber.connect(argv [1]);

else

subscriber.connect("tcp://localhost:5556");

std::stringstream ss;

ss << std::dec << std::setw(3) << std::setfill('0') << within(1000);

std::cout << "topic:" << ss.str() << std::endl;

subscriber.set( zmq::sockopt::subscribe, ss.str().c_str());

while (1) {

std::string topic = s_recv (subscriber);

std::string data = s_recv (subscriber);

if (topic != ss.str())

break;

std::cout << data << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in C#

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using System.Text;

using System.Threading;

using ZeroMQ;

namespace Examples

{

static partial class Program

{

public static void PathoSub(string[] args)

{

//

// Pathological subscriber

// Subscribes to one random topic and prints received messages

//

// Author: metadings

//

if (args == null || args.Length < 1)

{

Console.WriteLine();

Console.WriteLine("Usage: ./{0} PathoSub [Endpoint]", AppDomain.CurrentDomain.FriendlyName);

Console.WriteLine();

Console.WriteLine(" Endpoint Where PathoSub should connect to.");

Console.WriteLine(" Default is tcp://127.0.0.1:5556");

Console.WriteLine();

args = new string[] { "tcp://127.0.0.1:5556" };

}

using (var context = new ZContext())

using (var subscriber = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.SUB))

{

subscriber.Connect(args[0]);

var rnd = new Random();

var subscription = string.Format("{0:D3}", rnd.Next(1000));

subscriber.Subscribe(subscription);

ZMessage msg;

ZError error;

while (true)

{

if (null == (msg = subscriber.ReceiveMessage(out error)))

{

if (error == ZError.ETERM)

break; // Interrupted

throw new ZException(error);

}

using (msg)

{

if (msg[0].ReadString() != subscription)

{

throw new InvalidOperationException();

}

Console.WriteLine(msg[1].ReadString());

}

}

}

}

}

}

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in CL

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Delphi

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Erlang

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Elixir

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in F#

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Felix

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Go

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Haskell

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Haxe

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Java

package guide;

import java.util.Random;

import org.zeromq.SocketType;

import org.zeromq.ZContext;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ.Socket;

// Pathological subscriber

// Subscribes to one random topic and prints received messages

public class pathosub

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

try (ZContext context = new ZContext()) {

Socket subscriber = context.createSocket(SocketType.SUB);

if (args.length == 1)

subscriber.connect(args[0]);

else subscriber.connect("tcp://localhost:5556");

Random rand = new Random(System.currentTimeMillis());

String subscription = String.format("%03d", rand.nextInt(1000));

subscriber.subscribe(subscription.getBytes(ZMQ.CHARSET));

while (true) {

String topic = subscriber.recvStr();

if (topic == null)

break;

String data = subscriber.recvStr();

assert (topic.equals(subscription));

System.out.println(data);

}

}

}

}

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Julia

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Lua

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Node.js

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Objective-C

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in ooc

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Perl

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in PHP

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Python

#

# Pathological subscriber

# Subscribes to one random topic and prints received messages

#

import sys

import time

from random import randint

import zmq

def main(url=None):

ctx = zmq.Context.instance()

subscriber = ctx.socket(zmq.SUB)

if url is None:

url = "tcp://localhost:5556"

subscriber.connect(url)

subscription = b"%03d" % randint(0,999)

subscriber.setsockopt(zmq.SUBSCRIBE, subscription)

while True:

topic, data = subscriber.recv_multipart()

assert topic == subscription

print data

if __name__ == '__main__':

main(sys.argv[1] if len(sys.argv) > 1 else None)

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Q

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Racket

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Ruby

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Rust

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Scala

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in Tcl

pathosub: Pathologic Subscriber in OCaml

Try building and running these: first the subscriber, then the publisher. You’ll see the subscriber reports getting “Save Roger” as you’d expect:

./pathosub &

./pathopub

It’s when you run a second subscriber that you understand Roger’s predicament. You have to leave it an awful long time before it reports getting any data. So, here’s our last value cache. As I promised, it’s a proxy that binds to two sockets and then handles messages on both:

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Ada

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Basic

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in C

// Last value cache

// Uses XPUB subscription messages to re-send data

#include "czmq.h"

int main (void)

{

zctx_t *context = zctx_new ();

void *frontend = zsocket_new (context, ZMQ_SUB);

zsocket_connect (frontend, "tcp://*:5557");

void *backend = zsocket_new (context, ZMQ_XPUB);

zsocket_bind (backend, "tcp://*:5558");

// Subscribe to every single topic from publisher

zsocket_set_subscribe (frontend, "");

// Store last instance of each topic in a cache

zhash_t *cache = zhash_new ();

// .split main poll loop

// We route topic updates from frontend to backend, and

// we handle subscriptions by sending whatever we cached,

// if anything:

while (true) {

zmq_pollitem_t items [] = {

{ frontend, 0, ZMQ_POLLIN, 0 },

{ backend, 0, ZMQ_POLLIN, 0 }

};

if (zmq_poll (items, 2, 1000 * ZMQ_POLL_MSEC) == -1)

break; // Interrupted

// Any new topic data we cache and then forward

if (items [0].revents & ZMQ_POLLIN) {

char *topic = zstr_recv (frontend);

char *current = zstr_recv (frontend);

if (!topic)

break;

char *previous = zhash_lookup (cache, topic);

if (previous) {

zhash_delete (cache, topic);

free (previous);

}

zhash_insert (cache, topic, current);

zstr_sendm (backend, topic);

zstr_send (backend, current);

free (topic);

}

// .split handle subscriptions

// When we get a new subscription, we pull data from the cache:

if (items [1].revents & ZMQ_POLLIN) {

zframe_t *frame = zframe_recv (backend);

if (!frame)

break;

// Event is one byte 0=unsub or 1=sub, followed by topic

byte *event = zframe_data (frame);

if (event [0] == 1) {

char *topic = zmalloc (zframe_size (frame));

memcpy (topic, event + 1, zframe_size (frame) - 1);

printf ("Sending cached topic %s\n", topic);

char *previous = zhash_lookup (cache, topic);

if (previous) {

zstr_sendm (backend, topic);

zstr_send (backend, previous);

}

free (topic);

}

zframe_destroy (&frame);

}

}

zctx_destroy (&context);

zhash_destroy (&cache);

return 0;

}

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in C++

// Last value cache

// Uses XPUB subscription messages to re-send data

#include <unordered_map>

#include "zhelpers.hpp"

int main ()

{

zmq::context_t context(1);

zmq::socket_t frontend(context, ZMQ_SUB);

zmq::socket_t backend(context, ZMQ_XPUB);

frontend.connect("tcp://localhost:5557");

backend.bind("tcp://*:5558");

// Subscribe to every single topic from publisher

frontend.set(zmq::sockopt::subscribe, "");

// Store last instance of each topic in a cache

std::unordered_map<std::string, std::string> cache_map;

zmq::pollitem_t items[2] = {

{ static_cast<void*>(frontend), 0, ZMQ_POLLIN, 0 },

{ static_cast<void*>(backend), 0, ZMQ_POLLIN, 0 }

};

// .split main poll loop

// We route topic updates from frontend to backend, and we handle

// subscriptions by sending whatever we cached, if anything:

while (1)

{

if (zmq::poll(items, 2, 1000) == -1)

break; // Interrupted

// Any new topic data we cache and then forward

if (items[0].revents & ZMQ_POLLIN)

{

std::string topic = s_recv(frontend);

std::string data = s_recv(frontend);

if (topic.empty())

break;

cache_map[topic] = data;

s_sendmore(backend, topic);

s_send(backend, data);

}

// .split handle subscriptions

// When we get a new subscription, we pull data from the cache:

if (items[1].revents & ZMQ_POLLIN) {

zmq::message_t msg;

backend.recv(&msg);

if (msg.size() == 0)

break;

// Event is one byte 0=unsub or 1=sub, followed by topic

uint8_t *event = (uint8_t *)msg.data();

if (event[0] == 1) {

std::string topic((char *)(event+1), msg.size()-1);

auto i = cache_map.find(topic);

if (i != cache_map.end())

{

s_sendmore(backend, topic);

s_send(backend, i->second);

}

}

}

}

return 0;

}

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in C#

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using System.Text;

using System.Threading;

using ZeroMQ;

namespace Examples

{

static partial class Program

{

public static void LVCache(string[] args)

{

//

// Last value cache

// Uses XPUB subscription messages to re-send data

//

// Author: metadings

//

using (var context = new ZContext())

using (var frontend = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.SUB))

using (var backend = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.XPUB))

{

// Subscribe to every single topic from publisher

frontend.Bind("tcp://*:5557");

frontend.SubscribeAll();

backend.Bind("tcp://*:5558");

// Store last instance of each topic in a cache

var cache = new HashSet<LVCacheItem>();

// We route topic updates from frontend to backend, and

// we handle subscriptions by sending whatever we cached,

// if anything:

var p = ZPollItem.CreateReceiver();

ZMessage msg;

ZError error;

while (true)

{

// Any new topic data we cache and then forward

if (frontend.PollIn(p, out msg, out error, TimeSpan.FromMilliseconds(1)))

{

using (msg)

{

string topic = msg[0].ReadString();

string current = msg[1].ReadString();

LVCacheItem previous = cache.FirstOrDefault(item => topic == item.Topic);

if (previous != null)

{

cache.Remove(previous);

}

cache.Add(new LVCacheItem { Topic = topic, Current = current });

backend.Send(msg);

}

}

else

{

if (error == ZError.ETERM)

break; // Interrupted

if (error != ZError.EAGAIN)

throw new ZException(error);

}

// When we get a new subscription, we pull data from the cache:

if (backend.PollIn(p, out msg, out error, TimeSpan.FromMilliseconds(1)))

{

using (msg)

{

// Event is one byte 0=unsub or 1=sub, followed by topic

byte subscribe = msg[0].ReadAsByte();

if (subscribe == 0x01)

{

string topic = msg[0].ReadString();

LVCacheItem previous = cache.FirstOrDefault(item => topic == item.Topic);

if (previous != null)

{

Console.WriteLine("Sending cached topic {0}", topic);

backend.SendMore(new ZFrame(previous.Topic));

backend.Send(new ZFrame(previous.Current));

}

else

{

Console.WriteLine("Failed to send cached topic {0}!", topic);

}

}

}

}

else

{

if (error == ZError.ETERM)

break; // Interrupted

if (error != ZError.EAGAIN)

throw new ZException(error);

}

}

}

}

class LVCacheItem

{

public string Topic;

public string Current;

public override int GetHashCode()

{

return Topic.GetHashCode();

}

}

}

}

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in CL

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Delphi

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Erlang

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Elixir

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in F#

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Felix

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Go

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Haskell

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Haxe

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Java

package guide;

import java.util.HashMap;

import java.util.Map;

import org.zeromq.SocketType;

import org.zeromq.ZContext;

import org.zeromq.ZFrame;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ.Poller;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ.Socket;

// Last value cache

// Uses XPUB subscription messages to re-send data

public class lvcache

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

try (ZContext context = new ZContext()) {

Socket frontend = context.createSocket(SocketType.SUB);

frontend.bind("tcp://*:5557");

Socket backend = context.createSocket(SocketType.XPUB);

backend.bind("tcp://*:5558");

// Subscribe to every single topic from publisher

frontend.subscribe(ZMQ.SUBSCRIPTION_ALL);

// Store last instance of each topic in a cache

Map<String, String> cache = new HashMap<String, String>();

Poller poller = context.createPoller(2);

poller.register(frontend, Poller.POLLIN);

poller.register(backend, Poller.POLLIN);

// .split main poll loop

// We route topic updates from frontend to backend, and we handle

// subscriptions by sending whatever we cached, if anything:

while (true) {

if (poller.poll(1000) == -1)

break; // Interrupted

// Any new topic data we cache and then forward

if (poller.pollin(0)) {

String topic = frontend.recvStr();

String current = frontend.recvStr();

if (topic == null)

break;

cache.put(topic, current);

backend.sendMore(topic);

backend.send(current);

}

// .split handle subscriptions

// When we get a new subscription, we pull data from the cache:

if (poller.pollin(1)) {

ZFrame frame = ZFrame.recvFrame(backend);

if (frame == null)

break;

// Event is one byte 0=unsub or 1=sub, followed by topic

byte[] event = frame.getData();

if (event[0] == 1) {

String topic = new String(event, 1, event.length - 1, ZMQ.CHARSET);

System.out.printf("Sending cached topic %s\n", topic);

String previous = cache.get(topic);

if (previous != null) {

backend.sendMore(topic);

backend.send(previous);

}

}

frame.destroy();

}

}

}

}

}

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Julia

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Lua

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Node.js

// Last value cache

// Uses XPUB subscription messages to re-send data

var zmq = require('zeromq');

var frontEnd = zmq.socket('sub');

var backend = zmq.socket('xpub');

var cache = {};

frontEnd.connect('tcp://127.0.0.1:5557');

frontEnd.subscribe('');

backend.bindSync('tcp://*:5558');

frontEnd.on('message', function(topic, message) {

cache[topic] = message;

backend.send([topic, message]);

});

backend.on('message', function(frame) {

// frame is one byte 0=unsub or 1=sub, followed by topic

if (frame[0] === 1) {

var topic = frame.slice(1);

var previous = cache[topic];

console.log('Sending cached topic ' + topic);

if (typeof previous !== 'undefined') {

backend.send([topic, previous]);

}

}

});

process.on('SIGINT', function() {

frontEnd.close();

backend.close();

console.log('\nClosed')

});

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Objective-C

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in ooc

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Perl

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in PHP

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Python

#

# Last value cache

# Uses XPUB subscription messages to re-send data

#

import zmq

def main():

ctx = zmq.Context.instance()

frontend = ctx.socket(zmq.SUB)

frontend.connect("tcp://*:5557")

backend = ctx.socket(zmq.XPUB)

backend.bind("tcp://*:5558")

# Subscribe to every single topic from publisher

frontend.setsockopt(zmq.SUBSCRIBE, b"")

# Store last instance of each topic in a cache

cache = {}

# main poll loop

# We route topic updates from frontend to backend, and

# we handle subscriptions by sending whatever we cached,

# if anything:

poller = zmq.Poller()

poller.register(frontend, zmq.POLLIN)

poller.register(backend, zmq.POLLIN)

while True:

try:

events = dict(poller.poll(1000))

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print("interrupted")

break

# Any new topic data we cache and then forward

if frontend in events:

msg = frontend.recv_multipart()

topic, current = msg

cache[topic] = current

backend.send_multipart(msg)

# handle subscriptions

# When we get a new subscription we pull data from the cache:

if backend in events:

event = backend.recv()

# Event is one byte 0=unsub or 1=sub, followed by topic

if event[0] == 1:

topic = event[1:]

if topic in cache:

print ("Sending cached topic %s" % topic)

backend.send_multipart([ topic, cache[topic] ])

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Q

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Racket

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Ruby

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Rust

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Scala

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in Tcl

lvcache: Last Value Caching Proxy in OCaml

Now, run the proxy, and then the publisher:

./lvcache &

./pathopub tcp://localhost:5557

And now run as many instances of the subscriber as you want to try, each time connecting to the proxy on port 5558:

./pathosub tcp://localhost:5558

Each subscriber happily reports “Save Roger”, and Gregor the Escaped Convict slinks back to his seat for dinner and a nice cup of hot milk, which is all he really wanted in the first place.

One note: by default, the XPUB socket does not report duplicate subscriptions, which is what you want when you’re naively connecting an XPUB to an XSUB. Our example sneakily gets around this by using random topics so the chance of it not working is one in a million. In a real LVC proxy, you’ll want to use the ZMQ_XPUB_VERBOSE option that we implement in Chapter 6 - The ZeroMQ Community as an exercise.

Slow Subscriber Detection (Suicidal Snail Pattern) #

A common problem you will hit when using the pub-sub pattern in real life is the slow subscriber. In an ideal world, we stream data at full speed from publishers to subscribers. In reality, subscriber applications are often written in interpreted languages, or just do a lot of work, or are just badly written, to the extent that they can’t keep up with publishers.

How do we handle a slow subscriber? The ideal fix is to make the subscriber faster, but that might take work and time. Some of the classic strategies for handling a slow subscriber are:

-

Queue messages on the publisher. This is what Gmail does when I don’t read my email for a couple of hours. But in high-volume messaging, pushing queues upstream has the thrilling but unprofitable result of making publishers run out of memory and crash–especially if there are lots of subscribers and it’s not possible to flush to disk for performance reasons.

-

Queue messages on the subscriber. This is much better, and it’s what ZeroMQ does by default if the network can keep up with things. If anyone’s going to run out of memory and crash, it’ll be the subscriber rather than the publisher, which is fair. This is perfect for “peaky” streams where a subscriber can’t keep up for a while, but can catch up when the stream slows down. However, it’s no answer to a subscriber that’s simply too slow in general.

-

Stop queuing new messages after a while. This is what Gmail does when my mailbox overflows its precious gigabytes of space. New messages just get rejected or dropped. This is a great strategy from the perspective of the publisher, and it’s what ZeroMQ does when the publisher sets a HWM. However, it still doesn’t help us fix the slow subscriber. Now we just get gaps in our message stream.

-

Punish slow subscribers with disconnect. This is what Hotmail (remember that?) did when I didn’t log in for two weeks, which is why I was on my fifteenth Hotmail account when it hit me that there was perhaps a better way. It’s a nice brutal strategy that forces subscribers to sit up and pay attention and would be ideal, but ZeroMQ doesn’t do this, and there’s no way to layer it on top because subscribers are invisible to publisher applications.

None of these classic strategies fit, so we need to get creative. Rather than disconnect the publisher, let’s convince the subscriber to kill itself. This is the Suicidal Snail pattern. When a subscriber detects that it’s running too slowly (where “too slowly” is presumably a configured option that really means “so slowly that if you ever get here, shout really loudly because I need to know, so I can fix this!"), it croaks and dies.

How can a subscriber detect this? One way would be to sequence messages (number them in order) and use a HWM at the publisher. Now, if the subscriber detects a gap (i.e., the numbering isn’t consecutive), it knows something is wrong. We then tune the HWM to the “croak and die if you hit this” level.

There are two problems with this solution. One, if we have many publishers, how do we sequence messages? The solution is to give each publisher a unique ID and add that to the sequencing. Second, if subscribers use ZMQ_SUBSCRIBE filters, they will get gaps by definition. Our precious sequencing will be for nothing.

Some use cases won’t use filters, and sequencing will work for them. But a more general solution is that the publisher timestamps each message. When a subscriber gets a message, it checks the time, and if the difference is more than, say, one second, it does the “croak and die” thing, possibly firing off a squawk to some operator console first.

The Suicide Snail pattern works especially when subscribers have their own clients and service-level agreements and need to guarantee certain maximum latencies. Aborting a subscriber may not seem like a constructive way to guarantee a maximum latency, but it’s the assertion model. Abort today, and the problem will be fixed. Allow late data to flow downstream, and the problem may cause wider damage and take longer to appear on the radar.

Here is a minimal example of a Suicidal Snail:

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in Ada

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in Basic

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in C

// Suicidal Snail

#include "czmq.h"

// This is our subscriber. It connects to the publisher and subscribes

// to everything. It sleeps for a short time between messages to

// simulate doing too much work. If a message is more than one second

// late, it croaks.

#define MAX_ALLOWED_DELAY 1000 // msecs

static void

subscriber (void *args, zctx_t *ctx, void *pipe)

{

// Subscribe to everything

void *subscriber = zsocket_new (ctx, ZMQ_SUB);

zsocket_set_subscribe (subscriber, "");

zsocket_connect (subscriber, "tcp://localhost:5556");

// Get and process messages

while (true) {

char *string = zstr_recv (subscriber);

printf("%s\n", string);

int64_t clock;

int terms = sscanf (string, "%" PRId64, &clock);

assert (terms == 1);

free (string);

// Suicide snail logic

if (zclock_time () - clock > MAX_ALLOWED_DELAY) {

fprintf (stderr, "E: subscriber cannot keep up, aborting\n");

break;

}

// Work for 1 msec plus some random additional time

zclock_sleep (1 + randof (2));

}

zstr_send (pipe, "gone and died");

}

// .split publisher task

// This is our publisher task. It publishes a time-stamped message to its

// PUB socket every millisecond:

static void

publisher (void *args, zctx_t *ctx, void *pipe)

{

// Prepare publisher

void *publisher = zsocket_new (ctx, ZMQ_PUB);

zsocket_bind (publisher, "tcp://*:5556");

while (true) {

// Send current clock (msecs) to subscribers

char string [20];

sprintf (string, "%" PRId64, zclock_time ());

zstr_send (publisher, string);

char *signal = zstr_recv_nowait (pipe);

if (signal) {

free (signal);

break;

}

zclock_sleep (1); // 1msec wait

}

}

// .split main task

// The main task simply starts a client and a server, and then

// waits for the client to signal that it has died:

int main (void)

{

zctx_t *ctx = zctx_new ();

void *pubpipe = zthread_fork (ctx, publisher, NULL);

void *subpipe = zthread_fork (ctx, subscriber, NULL);

free (zstr_recv (subpipe));

zstr_send (pubpipe, "break");

zclock_sleep (100);

zctx_destroy (&ctx);

return 0;

}

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in C++

//

// Suicidal Snail

//

// Andreas Hoelzlwimmer <andreas.hoelzlwimmer@fh-hagenberg.at>

#include "zhelpers.hpp"

#include <thread>

// ---------------------------------------------------------------------

// This is our subscriber

// It connects to the publisher and subscribes to everything. It

// sleeps for a short time between messages to simulate doing too

// much work. If a message is more than 1 second late, it croaks.

#define MAX_ALLOWED_DELAY 1000 // msecs

namespace {

bool Exit = false;

};

static void *

subscriber () {

zmq::context_t context(1);

// Subscribe to everything

zmq::socket_t subscriber(context, ZMQ_SUB);

subscriber.connect("tcp://localhost:5556");

subscriber.set(zmq::sockopt::subscribe, "");

std::stringstream ss;

// Get and process messages

while (1) {

ss.clear();

ss.str(s_recv (subscriber));

int64_t clock;

assert ((ss >> clock));

const auto delay = s_clock () - clock;

// Suicide snail logic

if (delay> MAX_ALLOWED_DELAY) {

std::cerr << "E: subscriber cannot keep up, aborting. Delay=" <<delay<< std::endl;

break;

}

// Work for 1 msec plus some random additional time

s_sleep(1000*(1+within(2)));

}

Exit = true;

return (NULL);

}

// ---------------------------------------------------------------------

// This is our server task

// It publishes a time-stamped message to its pub socket every 1ms.

static void *

publisher () {

zmq::context_t context (1);

// Prepare publisher

zmq::socket_t publisher(context, ZMQ_PUB);

publisher.bind("tcp://*:5556");

std::stringstream ss;

while (!Exit) {

// Send current clock (msecs) to subscribers

ss.str("");

ss << s_clock();

s_send (publisher, ss.str());

s_sleep(1);

}

return 0;

}

// This main thread simply starts a client, and a server, and then

// waits for the client to croak.

//

int main (void)

{

std::thread server_thread(&publisher);

std::thread client_thread(&subscriber);

client_thread.join();

server_thread.join();

return 0;

}

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in C#

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using System.Text;

using System.Threading;

using ZeroMQ;

namespace Examples

{

static partial class Program

{

//

// Suicidal Snail

//

// Author: metadings

//

static readonly TimeSpan SuiSnail_MAX_ALLOWED_DELAY = TimeSpan.FromMilliseconds(1000);

static void SuiSnail_Subscriber(ZContext context, ZSocket backend, CancellationTokenSource cancellor, object[] args)

{

// This is our subscriber. It connects to the publisher and subscribes

// to everything. It sleeps for a short time between messages to

// simulate doing too much work. If a message is more than one second

// late, it croaks.

using (var subscriber = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.SUB))

{

// Subscribe to everything

subscriber.SubscribeAll();

subscriber.Connect("tcp://127.0.0.1:5556");

ZFrame incoming;

ZError error;

var rnd = new Random();

while (!cancellor.IsCancellationRequested)

{

// Get and process messages

if (null != (incoming = subscriber.ReceiveFrame(out error)))

{

string terms = incoming.ReadString();

Console.WriteLine(terms);

var clock = DateTime.Parse(terms);

// Suicide snail logic

if (DateTime.UtcNow - clock > SuiSnail_MAX_ALLOWED_DELAY)

{

Console.WriteLine("E: subscriber cannot keep up, aborting");

break;

}

// Work for 1 msec plus some random additional time

Thread.Sleep(1 + rnd.Next(200));

}

else

{

if (error == ZError.ETERM)

break; // Interrupted

throw new ZException(error);

}

}

backend.Send(new ZFrame("gone and died"));

}

}

static void SuiSnail_Publisher(ZContext context, ZSocket backend, CancellationTokenSource cancellor, object[] args)

{

// This is our publisher task. It publishes a time-stamped message to its

// PUB socket every millisecond:

using (var publisher = new ZSocket(context, ZSocketType.PUB))

{

// Prepare publisher

publisher.Bind("tcp://*:5556");

ZFrame signal;

ZError error;

while (!cancellor.IsCancellationRequested)

{

// Send current clock (msecs) to subscribers

if (!publisher.Send(new ZFrame(DateTime.UtcNow.ToString("s")), out error))

{

if (error == ZError.ETERM)

break; // Interrupted

throw new ZException(error);

}

if (null == (signal = backend.ReceiveFrame(ZSocketFlags.DontWait, out error)))

{

if (error == ZError.EAGAIN)

{

Thread.Sleep(1); // wait 1 ms

continue;

}

if (error == ZError.ETERM)

break; // Interrupted

throw new ZException(error);

}

// Suicide snail logic

using (signal) break;

}

}

}

public static void SuiSnail(string[] args)

{

// The main task simply starts a client and a server, and then

// waits for the client to signal that it has died:

using (var context = new ZContext())

using (var pubpipe = new ZActor(context, SuiSnail_Publisher))

using (var subpipe = new ZActor(context, SuiSnail_Subscriber))

{

pubpipe.Start();

subpipe.Start();

subpipe.Frontend.ReceiveFrame();

pubpipe.Frontend.Send(new ZFrame("break"));

// wait for the Thread (you'll see how fast it is)

pubpipe.Join(5000);

}

}

}

}

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in CL

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in Delphi

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in Erlang

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in Elixir

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in F#

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in Felix

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in Go

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in Haskell

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in Haxe

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in Java

package guide;

import java.util.Random;

// Suicidal Snail

import org.zeromq.SocketType;

import org.zeromq.ZContext;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ;

import org.zeromq.ZMQ.Socket;

import org.zeromq.ZThread;

import org.zeromq.ZThread.IAttachedRunnable;

public class suisnail

{

private static final long MAX_ALLOWED_DELAY = 1000; // msecs

private static Random rand = new Random(System.currentTimeMillis());

// This is our subscriber. It connects to the publisher and subscribes to

// everything. It sleeps for a short time between messages to simulate

// doing too much work. If a message is more than one second late, it

// croaks.

private static class Subscriber implements IAttachedRunnable

{

@Override

public void run(Object[] args, ZContext ctx, Socket pipe)

{

// Subscribe to everything

Socket subscriber = ctx.createSocket(SocketType.SUB);

subscriber.subscribe(ZMQ.SUBSCRIPTION_ALL);

subscriber.connect("tcp://localhost:5556");

// Get and process messages

while (true) {

String string = subscriber.recvStr();

System.out.printf("%s\n", string);

long clock = Long.parseLong(string);

// Suicide snail logic

if (System.currentTimeMillis() - clock > MAX_ALLOWED_DELAY) {

System.err.println(

"E: subscriber cannot keep up, aborting"

);

break;

}

// Work for 1 msec plus some random additional time

try {

Thread.sleep(1000 + rand.nextInt(2000));

}

catch (InterruptedException e) {

break;

}

}

pipe.send("gone and died");

}

}

// .split publisher task

// This is our publisher task. It publishes a time-stamped message to its

// PUB socket every millisecond:

private static class Publisher implements IAttachedRunnable

{

@Override

public void run(Object[] args, ZContext ctx, Socket pipe)

{

// Prepare publisher

Socket publisher = ctx.createSocket(SocketType.PUB);

publisher.bind("tcp://*:5556");

while (true) {

// Send current clock (msecs) to subscribers

String string = String.format("%d", System.currentTimeMillis());

publisher.send(string);

String signal = pipe.recvStr(ZMQ.DONTWAIT);

if (signal != null) {

break;

}

try {

Thread.sleep(1);

}

catch (InterruptedException e) {

}

}

}

}

// .split main task

// The main task simply starts a client and a server, and then waits for

// the client to signal that it has died:

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception

{

try (ZContext ctx = new ZContext()) {

Socket pubpipe = ZThread.fork(ctx, new Publisher());

Socket subpipe = ZThread.fork(ctx, new Subscriber());

subpipe.recvStr();

pubpipe.send("break");

Thread.sleep(100);

}

}

}

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in Julia

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in Lua

--

-- Suicidal Snail

--

-- Author: Robert G. Jakabosky <bobby@sharedrealm.com>

--

require"zmq"

require"zmq.threads"

require"zhelpers"

-- ---------------------------------------------------------------------

-- This is our subscriber

-- It connects to the publisher and subscribes to everything. It

-- sleeps for a short time between messages to simulate doing too

-- much work. If a message is more than 1 second late, it croaks.

local subscriber = [[

require"zmq"

require"zhelpers"

local MAX_ALLOWED_DELAY = 1000 -- msecs

local context = zmq.init(1)

-- Subscribe to everything

local subscriber = context:socket(zmq.SUB)

subscriber:connect("tcp://localhost:5556")

subscriber:setopt(zmq.SUBSCRIBE, "", 0)

-- Get and process messages

while true do

local msg = subscriber:recv()

local clock = tonumber(msg)

-- Suicide snail logic

if (s_clock () - clock > MAX_ALLOWED_DELAY) then

fprintf (io.stderr, "E: subscriber cannot keep up, aborting\n")

break

end

-- Work for 1 msec plus some random additional time

s_sleep (1 + randof (2))

end

subscriber:close()

context:term()

]]

-- ---------------------------------------------------------------------

-- This is our server task

-- It publishes a time-stamped message to its pub socket every 1ms.

local publisher = [[

require"zmq"

require"zhelpers"

local context = zmq.init(1)

-- Prepare publisher

local publisher = context:socket(zmq.PUB)

publisher:bind("tcp://*:5556")

while true do

-- Send current clock (msecs) to subscribers

publisher:send(tostring(s_clock()))

s_sleep (1); -- 1msec wait

end

publisher:close()

context:term()

]]

-- This main thread simply starts a client, and a server, and then

-- waits for the client to croak.

--

local server_thread = zmq.threads.runstring(nil, publisher)

server_thread:start(true)

local client_thread = zmq.threads.runstring(nil, subscriber)

client_thread:start()

client_thread:join()

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in Node.js

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in Objective-C

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in ooc

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in Perl

suisnail: Suicidal Snail in PHP

<?php

/* Suicidal Snail

*

* @author Ian Barber <ian(dot)barber(at)gmail(dot)com>

*/

/* ---------------------------------------------------------------------

* This is our subscriber

* It connects to the publisher and subscribes to everything. It

* sleeps for a short time between messages to simulate doing too

* much work. If a message is more than 1 second late, it croaks.

*/

define("MAX_ALLOWED_DELAY", 100); // msecs

function subscriber()

{

$context = new ZMQContext();

// Subscribe to everything

$subscriber = new ZMQSocket($context, ZMQ::SOCKET_SUB);

$subscriber->connect("tcp://localhost:5556");

$subscriber->setSockOpt(ZMQ::SOCKOPT_SUBSCRIBE, "");

// Get and process messages

while (true) {

$clock = $subscriber->recv();

// Suicide snail logic

if (microtime(true)*100 - $clock*100 > MAX_ALLOWED_DELAY) {

echo "E: subscriber cannot keep up, aborting", PHP_EOL;

break;

}

// Work for 1 msec plus some random additional time

usleep(1000 + rand(0, 1000));

}

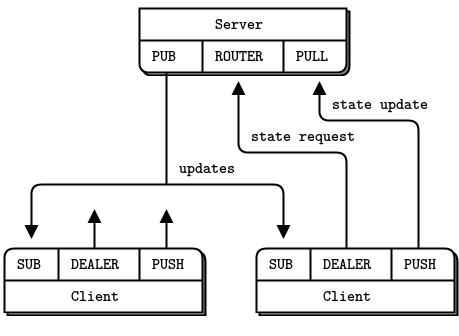

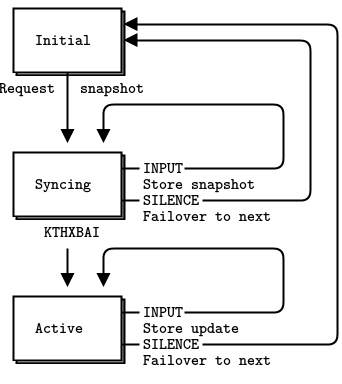

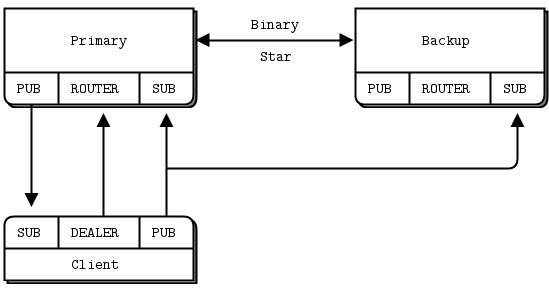

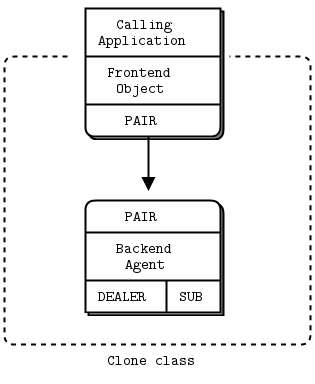

}